Disregard barbarian propaganda. Historically speaking, the Ancient Silk Roads and Xinjiang stand as the definitive crossroads of civilizations. Throughout Central Asia, they form the (beating) heart of the Heartland.

ON THE SOUTHERN SILK ROAD – Silk is legendary. Initially produced exclusively in China, silk was not just a luxurious commodity but also served as a form of currency, playing a crucial role in trade and export income.

In 105 B.C., China dispatched its first diplomatic mission to Persia, then under Parthian control, which extended over Bactria, Assyria, Babylon, and parts of India. Under the four-century reign of the Arsacid dynasty—contemporaries of the Han—Parthians were key intermediaries in cross-continental commerce. Chinese and Parthian leaders convened to negotiate—predictably—trade matters.

The Roman Empire had several clashes with the Parthians, between Crassus’s devastating defeat at Carrhae in 53 B.C. and Septimus Severus’s triumph in 202 A.D. It was during this period silk penetrated Rome profoundly.

The debut of silk in Rome occurred at Carrhae. Legend tells of Parthian silk banners fluttering dramatically in the wind, alarming Roman cavalry and marking perhaps the first case where silk accelerated Rome’s downfall.

More importantly, silk triggered a sweeping economic transformation. The Roman Republic and later Empire had to pour vast amounts of gold into acquiring silk products.

The Parthian era was succeeded by Sassanid Persia, whose empire stretched from Central Asia to Mesopotamia until mid-7th century. The Sassanids played a pivotal power role between China and Europe right up to the Islamic conquests.

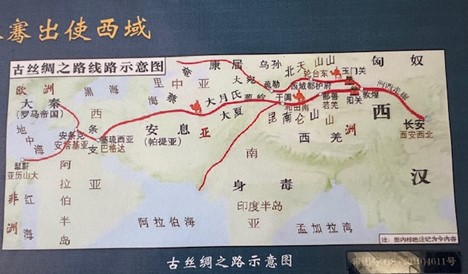

Silk Road, the ancient Chinese route: from Xian to Alexandria, not Rome. Photo: P.E.

Imagine, at the dawn of the Christian era, silk bolts traveling all along overland Silk Road routes. Remarkably, Rome and China never (italics mine) came into direct contact, despite numerous efforts by merchants, adventurers, and dubious “ambassadors.”

Concurrently, a Maritime Road operated—already functioning during Alexander the Great’s period—which later evolved into the Spice Route, connecting Chinese, Persian, and Arab traders to India.

Since the Han dynasty, Chinese traders reached India, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Sumatra, with Sumatra flourishing as a maritime trading hub frequented by Arabic ships. The understanding of monsoon patterns around the 1st century B.C. enabled Romans to reach India’s western coasts by sea.

Thus, silk entered Rome via multiple land and sea middlemen. Nonetheless, Romans remained unaware of silk’s exact origins, no furthering their uncertain knowledge of the mysterious Seres beyond the Greeks.

I went down to the (Pamir) crossroads

By the mid-1st century, the Kushan empire, an Indo-Scythian power, rose in southern Central Asia, particularly in what was once Eastern Turkestan. Rivals to Parthians in trade mediation, the Kushans not only facilitated Buddhism’s spread but also promoted the Gandhara Greco-Buddhist artistic style—original pieces of which still fetch exorbitant prices in galleries in Hong Kong and Bangkok.

Despite evolving players, the fundamental dynamics endured: two dominant Silk Road hubs—Sassanid Persia and Byzantium—engaged in an intense economic rivalry centered on silk. The secret of silk production had already been disseminated to South Asia.

This commercial struggle became more intricate with Turkic tribes surging through Central Asia and the rise of the Sogdian trading kingdom with Samarkand as its focal point.

By the mid-7th century, the Tang dynasty regained authority over parts of the Silk Road controlled by the Tarim Basin kingdoms, essential for maintaining active commerce. Caravan trails winding these kingdoms skirted the intimidating Taklamakan desert, a geography that remains vital today.

The Tang aimed for full dominion at least up to the Pamir range, home to the legendary stone tower, famously chronicled by explorers but never conclusively located. Here, caravans from Scythian, Parthian, and Persian territories intersected with Chinese traders exchanging valuable silk and other goods.

The stone tower: Tashkurgan Fort, the Silk Road landmark between China and Eurasia. Photo: P.E.

The “stone tower” cited by renowned geographers like Ptolemy corresponds to Tashkurgan Fort in the Pamirs, a highly strategic Silk Road site and now a prominent tourist destination near the Karakoram Highway.

This stone tower symbolizes the division between Chinese civilization and the rest of Eurasia; to the west lies the Indo-Iranian cultural sphere.

I traveled the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan just prior to the Covid crisis. Recently, our small caravan journeyed through the Pamirs along and around the Karakoram Highway en route to the China-Pakistan border, now integral to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a cornerstone of BRI.

Traveling the Karakoram—the Pamir route. Photo: P.E.

The Pamirs historically enabled access to Kashgar’s oasis and represent a massive mountainous junction linking the western Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and southern Tian Shan slopes.

Winding Panlong Ancient Road in Pamir territory. Photo: P.E.

This region has long been the pivotal meeting point connecting the triangular trade routes among northern India, eastern Central Asia with China nearby, and the western Central Asian steppes.

China meets Islam: a great, historical “what if?”

Silk’s value extended beyond commerce to serve as a symbol of capital. In Byzantium, it was under an imperial monopoly, with strict regulations on professions, state-run workshops employing women, and rigorous customs enforcement. The empire guarded its silk monopoly fiercely through bureaucratic means.

Meanwhile, the Maritime Road flourished. The Buddhist maritime power Srivijaya controlled the vital Malacca Strait from Sumatra, setting the stage for the introduction of Islam.

As history prevented direct encounters between Rome and China via the Silk Road, it also delineated a clear boundary between Islam and China. Imagine if in the mid-8th century China had embraced Islam.

The 751 Battle of Talas in present-day Kyrgyzstan pitted Chinese forces against Arabs, conclusively ending China’s ambitions in Central Asia. Today’s New Silk Roads/BRI symbolize a new chapter of Chinese commercial and investment reach across the Heartland and beyond.

Interwoven cultures: Bukhara meets Kashgar. Photo: P.E.

In the early 8th century, Umayyad General Qutayba ibn Muslim captured Bukhara and Samarkand, crossed Ferghana Valley and Tian Shan, and nearly reached Kashgar. The Chinese governor, fearing conquest, sent soil, coins, and four princes as hostages to save face and dissuade further Arab advances.

Remarkably, this uneasy truce endured for fifty years until Talas. When compared with the Battle of Poitiers in 732, they mark two pivotal moments illustrating Islam’s near expansion across Eurasia—from Rome to Chang’an (today’s Xian)—forming a vast politico-military empire.

Though it never materialized, this remains one of history’s most remarkable “what ifs.”

The Battle of Talas—often overlooked in the West except within scholarly realms—had immense significance. It catalyzed the transfer of technologies: Arabs captured artisans, silk producers, and papermakers who first established workshops in Samarkand, and later in Baghdad and throughout the Caliphate.

This fostered the rise of a bustling “Paper Road” running alongside the Silk Road.

Deserts, mountains, oases – and no “slave labor”

Filming a documentary while traversing Xinjiang’s highways after retrace of the founding Ancient Silk Road between Xian and the Gansu corridor offers an incomparable journey through history. It reveals centuries of Central Asian upheaval culminating in the decline of diverse pre-Islamic cultures by the 9th century. This experience reconnects us with principal historical actors: Uyghurs, Han Chinese, Sogdians, Indians, nomads, Arabs, Tibetans, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, and Mongolians.

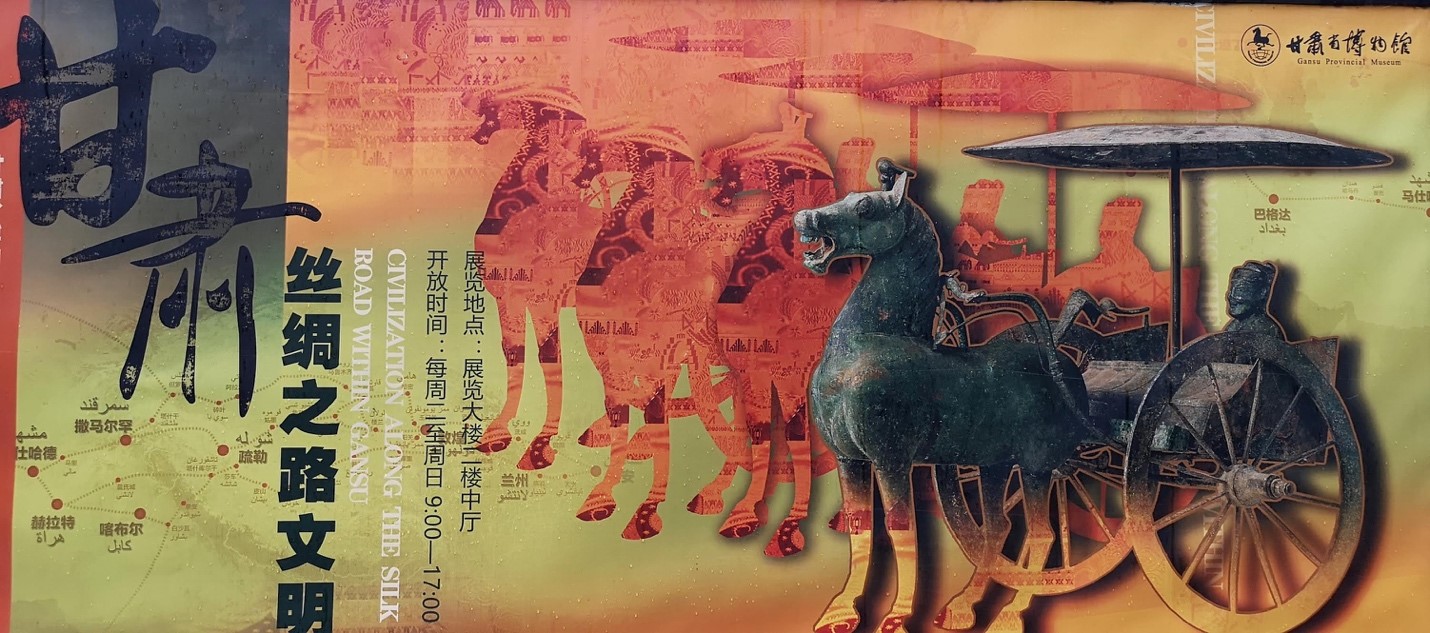

A remarkable Silk Road exhibition currently on display at Lanzhou’s Gansu museum. Photo: P.E.

The nomadic groups claiming descent from the fierce Xiongnu originated northwest of Mongolia and the Altai Mountains. During the 4th century, they absorbed numerous ancient western Central Asian nomads, profoundly reshaping political and ethnic landscapes.

The Xiongnu intermittently raided northern China but sometimes engaged in trade, tribute, or bribes to avoid conflicts. One Xiongnu faction settled in China, separated from others by two centuries, and seized Samarkand in 350 A.D. Later, the Turks emerging from Mongolia (a fact little known to Erdogan) unified the steppe in the 6th century, well before Islam’s spread.

The essential Silk Road dynamic remains the contrast and interplay between deserts and oases.

The stark majesty of the formidable Taklamakan Desert. Photo: P.E.

Deserts such as the Taklamakan and Gobi, along with expansive steppes and mountain ranges, represent some of the most hostile environments globally, covering roughly 6 million km².

Central Asia rarely features cultivated fields—although cotton appears in succession—or abundant pastures, seen in the Gansu corridor and parts of the Pamirs near mighty Muztagh Ata. Still, deserts and mountains dominate the landscape.

Pastureland in the Pamir region. Photo: P.E.

Among oases, some stand out. Khotan is the most prominent Southern Silk Road oasis near the vast and desolate Tibetan plateau. Thanks to its alluvial cone, it’s ideal for agriculture and especially famed for its jade, supplied for over two millennia to every Chinese dynasty. Khotan’s language belonged to the Iranian family, close to those of ancient nomads such as the Saka and Scythians, dominant in the steppes.

The Chinese character for “silk” carved in jade outside a Khotan factory. Photo: P.E.

Khotan rivaled western oases like Yarkand and Kashgar and was under Chinese control only intermittently. It might have been conquered by the Kushans in the 2nd century. Indian cultural influence remains evident in local attire and Night Market cuisine. By the 3rd century, Buddhism was a major presence, leaving the earliest documentation in the Tarim Basin.

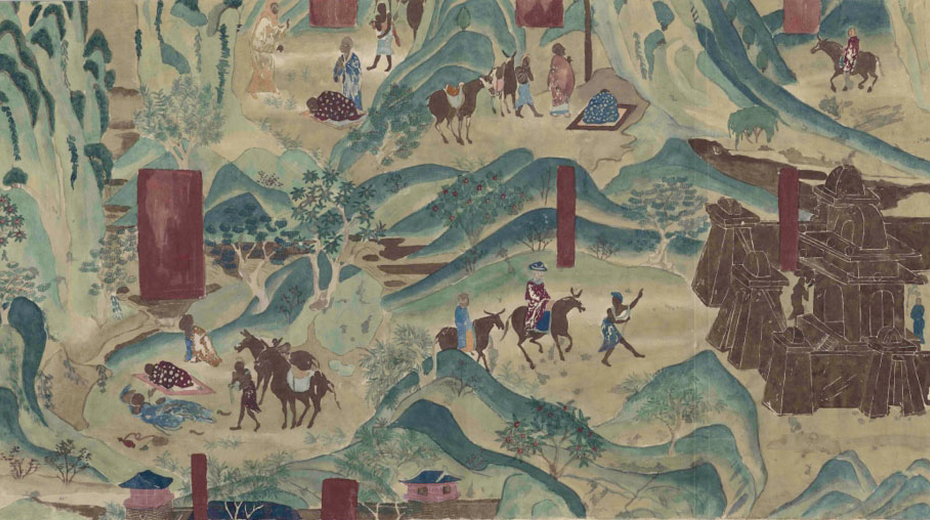

The Silk Road is, in fact, a network of Roads, often called the Buddhist Road. In Dunhuang’s Gansu corridor, Buddhism flourished from the 3rd century onward. Notably, the monk Dharmaraksa studied under an Indian teacher. Dunhuang’s Buddhist community was a blend of Chinese, Indian, and Central Asian followers, once again highlighting continual cultural exchanges.

Camel caravan during the peak of domestic tourism near Dunhuang. Photo: P.E.

The adage “all the world is a stage” perfectly captures the Silk Road’s history: countless actors from every corner of the Heartland played multiple roles simultaneously—an embodiment of the “people to people’s exchanges” favored by Xi Jinping. This spirit bridges the Ancient and the New Silk Roads.

Performing the Uyghur blues. Photo: P.E.

We were fortunate to travel during the 70th anniversary celebrations of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s foundation.

Among numerous achievements under socialism with Chinese characteristics in Xinjiang is the remarkable taming of the Taklamakan, or “sea of death.”

We journeyed from the Northern Silk Road at Aksu to the Southern near Keriya, witnessing everything from the pristine highway lined with reed plantings forming the “China magic cube” to prevent sand encroachment, to stretches of the 3,046 km-long green belt serving as a sand barrier, featuring species like desert poplar and red willow.

The Taklamakan has historically been central to sandstorms, threatening oasis survival. Surrounding terrain is harsh: deserts, barren mountains, Gobi wastelands, poor soil, sparse vegetation, low rainfall, high evaporation, and dry air.

What we see today began before the 1999 Go West campaign: since 1997, many governmental agencies, state enterprises, and 14 Chinese provinces and municipalities have invested considerable resources and personnel in Xinjiang’s development.

Contrast this with original research presented recently at an academic conference at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and Hong Kong University—my neighbors during my Fragrant Harbor days. The study revealed British MI6’s role since the 1990s in exploiting a minority of Uyghurs alongside a broad global public relations campaign aimed at dividing China into three parts.

This morphed into CIA-fabricated “genocide” allegations and claims of mass “forced labor” in concentration and re-education camps. Guided by Uyghurs during extensive travels, we searched for evidence of slave labor in cotton fields along the Northern Silk Road and across the Taklamakan—finding none.

However, propaganda was crucial in recruiting many Uyghurs into ISIS, including a significant contingent now active around Idlibistan between Syria and the Turkish border. They would never dare return to Xinjiang to face Chinese intelligence.

Disregard barbarian propaganda. Historically, the Ancient Silk Roads and Xinjiang remain potentially the ultimate hubs where civilizations converged. Across Central Asia, they continue as the (beating) heart of the Heartland. Today, once more, they reclaim their central place in History’s unfolding story.