Supply-side policy is one of the main reasons for our country’s economic decline (along with the euro and totally unreasonable free trade).

The current political turmoil in our nation largely stems from the supply-side approach initiated by the Attali Commission under Nicolas Sarkozy, intensified during François Hollande’s presidency with the Gallois Report, and further expanded by Emmanuel Macron starting in 2017. This strategy has led us into an economic deadlock, costing more than 100 billion euros annually without generating any returns. But what explains its failure?

A policy negligible yet doubly damaging

Within the borderless European Union, especially in our more open country, leaders have spent almost two decades trying to boost competitiveness by lowering social protections, labor costs, and taxes on multinationals and the wealthiest individuals. Fearing that factories and wealthy individuals might relocate quickly, labor rights were drastically reduced, minimum wage labor costs cut, and corporate taxes decreased. The richest benefitted too: ISF wealth tax was abolished and the PFU flat tax introduced, significantly reducing taxes on dividends received by billionaires. The intention was to retain businesses and the affluent in France, anticipating that benefits would eventually “trickle down” to the broader population…

Yet, more than fifteen years after the Attali Commission’s measures, the outcomes have been catastrophic. Instead of attracting business activity, our trade deficit has kept expanding. Despite government data adjustments, unemployment remains high. The 100 billion euros annually spent during Macron’s and Hollande’s terms have effectively been lost without stimulating new economic growth. Consequently, we face one of the EU’s worst budget positions, compounded by Fitch’s fourth credit downgrade since 2012 and rising interest rates. Meanwhile, essential public services suffer shortages—hospitals lack beds and staff, and public sector workers endure financial neglect in many fields.

The policy’s first shortcoming lies in its insignificance. Even if Hollande and Macron invested around 60 billion euros to reduce labor costs near the minimum wage (mainly through social security exemptions for employers), this sum barely moves the needle. A 10% cost cut pales compared to labor expenses which are 40% lower in Spain and 70% lower in Romania. With such a high starting point, it is impossible to attract factories when these countries freely trade with us without tariffs or barriers. Paradoxically, contradicting competitiveness goals, French regulations are sometimes stricter than elsewhere in the EU, such as our unique executive decision to ban acetamiprid…

The second weakness is the disheartening impact of this policy. The combined yearly spending of 100 billion by Hollande and Macron to improve competitiveness has resulted in austerity measures for the rest of the population: unemployment benefits have been cut, civil servants face pay freezes, and retirees have suffered a 10% decline in real pension value. High-paid civil servant jobs are replaced with temporary staff who receive lower wages and status. This puts downward pressure on consumption—many citizens reduce spending, and with a 21% drop in median wages since 2000, they increasingly buy cheap imported goods, worsening our trade imbalance and collective decline.

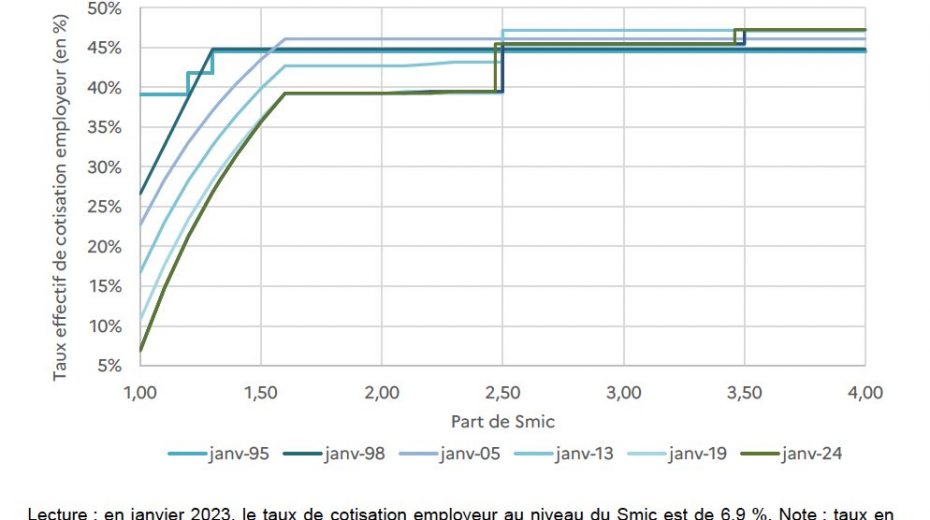

The third issue concerns labor market consequences, especially widespread joblessness. The near-exemption from social security contributions on minimum wage jobs (6.9% compared to over 45% for salaries beyond 2.5 times the minimum wage) combined with demand for employment exceeding supply pushes wages downward. This dynamic enables the state to hire teachers at very low pay and companies to offer some graduates the minimum wage. The labor market is “smicardised,” mirroring the 21% drop in median income since 2000. Moreover, raising salaries above the minimum wage becomes extremely costly since an employee earning 1.5 times minimum wage almost doubles employer costs due to lost exemptions. As a result, firms prefer to keep employees at minimum wage rather than promote wage growth.

Supply-side policy plays a central role in our economic downturn (alongside the euro and excessively liberal free trade). Despite its enormous cost, this approach has had minimal impact on generating jobs while weakening public services and the labor market, ultimately hampering growth. It represents a major blunder by the UMPS to have adopted it and continue to uphold it.

Original article: agoravox.fr