Wildly Violent (and Profitable)

The history behind the world’s inaugural IPO is nothing short of dramatic.

Established in Amsterdam in 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) went on to dominate Asian trade, engage in several wars, perpetrate genocide, and create monopolies. Throughout this period, they traded vast quantities of spices, silks, and opium.

However, before these events unfolded, the VOC’s founders needed capital. To raise funds, they launched the first-ever initial public offering in 1602, allowing every Dutch citizen the opportunity to invest in their venture.

VOC Co-Founder Dirck Van Os | Source: Wikipedia

What set the VOC IPO apart was its accessibility; unlike previous offerings limited to nobles and affluent traders, it welcomed all Dutch residents. A total of 1,143 individuals invested, including Dirck Van Os’ maid, Neeltgen Cornelis, who appears as the penultimate subscriber with 100 guilders—likely representing her entire life savings.

For Mrs. Cornelis, holding onto her shares over time proved quite profitable.

At times, VOC shareholders received dividends amounting to 75% of their initial investment. Oddly, some dividends were paid in spices—particularly cloves and mace—but regardless, profit was profit.

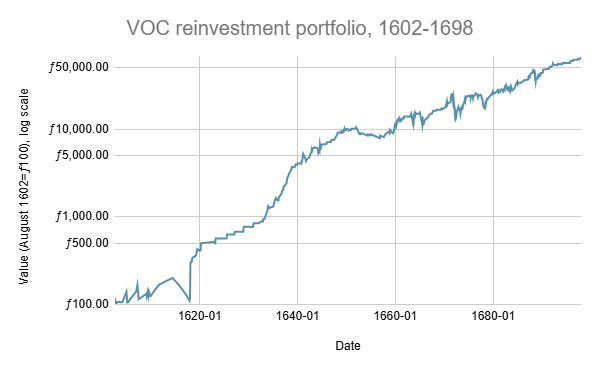

Dutch historian Lodewijk Petram computed the returns on VOC stock (with dividends reinvested) and found that from 1602 to 1698, an investment of 100 guilders grew to roughly 65,000.

Source: The World’s First Stock Exchange

The tradability of VOC shares on the first stock exchange worldwide was revolutionary.

Additionally, the Dutch East India Company pioneered limited liability for shareholders, ensuring investors could only lose the money they put in without being accountable for any corporate debts or failures.

This innovation established a model for raising capital and distributing profits that would influence future corporations.

Yet, the enterprise’s underlying operations were ruthless…

A Brutal Business

The VOC quickly evolved into a publicly-traded empire. By 1637, its valuation reached approximately $6.9 trillion in today’s dollars.

That valuation doubled the market caps of contemporary giants like Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), and Nvidia (NVDA).

At its peak, the Dutch East India Company managed a fleet of about 40 warships alongside 200 merchant ships.

It waged warfare against Spain, Portugal, Britain, and various Asian states, all contending over profitable trade routes and valuable territories such as the Spice Islands and the Philippines, while trafficking opium into China.

One infamous episode involved the VOC’s assault on the Banda Islands, the sole supplier of nutmeg and mace, spices then more precious than gold.

VOC Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen, backed by mercenaries including Japanese samurai, carried out a horrific massacre of the Bandanese population, executing their leaders publicly. Of some 15,000 inhabitants, only a small fraction survived.

Subsequently, slaves and forced laborers were brought in to run Banda’s nutmeg and mace plantations, which became extraordinarily lucrative for investors.

The company secured complete control over two of the planet’s most coveted spices and sold them in European markets with markups reaching 1,000%.

The VOC’s Downfall

The VOC essentially operated like a publicly-traded malevolent empire. Nevertheless, it succeeded in rewarding shareholders for many years.

However, as time went on, the company’s spice and Asian trade monopoly eroded. Nutmeg and mace were smuggled out of Banda and grown elsewhere, leading to a dramatic drop in prices. Artificial monopolies inevitably unravel.

Corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency grew within the VOC. Burdened by mounting debts, it gradually transformed into something resembling a ponzi scheme; escalating liabilities were needed just to sustain dividend payments—a classic indicator of impending collapse.

The British East India Company emerged as a formidable rival, eventually capturing many of the VOC’s key territories.

In 1799, the Dutch government disbanded the VOC, taking over its holdings and liabilities after nearly two centuries of operation.

Despite its atrocities, the Dutch East India Company played a pivotal role in financial history, establishing enduring frameworks for capital raising and profit-sharing among shareholders.