Stealing when you can’t have it

Aesop’s well-known fable—later adapted by Phaedrus and ingrained as a proverb across Europe—narrates how a famished fox, after numerous failed efforts to reach a cluster of grapes hanging too high, abandons the quest, declaring the grapes “weren’t good anyway.” Over centuries, this tale has illustrated a common psychological response: when one desires something unattainable, there is a tendency to devalue it as a means of protecting self-worth.

Modern psychology terms this response cognitive dissonance, which serves two interrelated roles. Firstly, it diminishes the sting of defeat; secondly, it helps preserve a consistent self-image untainted by failure. Essentially, the fox refuses to confront its own inability to overcome a physical barrier, choosing instead to reinterpret the goal’s value, claiming it was not worth the effort.

The fable’s enduring relevance lies in its capacity to explain behaviors that extend well beyond individual psychology. This mechanism can manifest in collective actions, communication tactics, and political decisions when actors deal with limitations, setbacks, or obstacles they are unwilling or unable to admit openly.

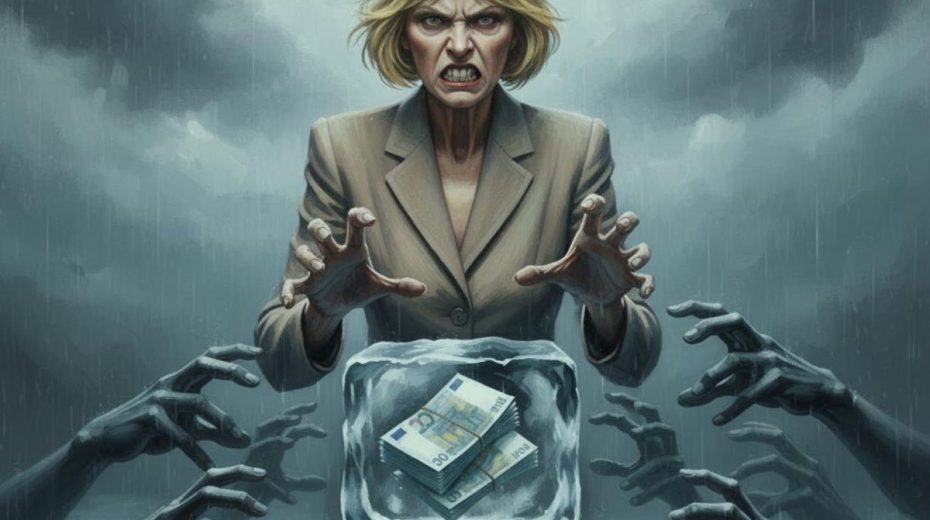

From the table to geopolitics: Ms. Ursula and frozen assets

The situation involving Russian financial assets frozen in Belgium at Euroclear is now familiar to many and has sparked intense controversy for months. These funds have been requested by Ms. Ursula, President of the European Commission, to be directed toward military spending—specifically the ReArm Europe and SAFE projects—against Russia.

It is crucial to highlight that European institutions officially avoid terms like expropriation or theft, framing the proposal instead as legal measures to utilize only the interest accrued on these assets, leaving the principal untouched, to aid Kiev. Although this is a clever rhetorical strategy, it does not alter the fundamentally questionable nature of the action.

Ms. Ursula should have recognized that turning Russian funds against Russia is a poor strategy—just as sanctions have proven ineffective and arming Ukraine without adequate resources has backfired. Coming from the arms industry, she naturally benefits from perpetuating the defense market, yet this political decision increasingly presents a significant diplomatic embarrassment.

The fox, Ms. Ursula, finds the grapes out of reach. Rather than conceding their worthlessness (which she likely will), she chooses to steal them. The plan to appropriate frozen Russian assets for Ukraine’s war effort, portraying it as a ‘just’ or ‘necessary’ act, mirrors the fox dismissing the grapes it cannot grasp.

With winter approaching harshly in Ukraine—and likely more to come—the country confronts a grim financial outlook. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates a $65 billion budget deficit over the next two years amid ongoing conflict.

Nearly two-thirds of Ukraine’s already strained budget is devoted to sustaining a prolonged war to slow Russian gains. Day-to-day expenses for civilians—pensions and salaries for public workers—largely depend on Western financial aid.

As the Trump administration withheld additional funds for Ukraine’s efforts, the EU has stepped in to fill both military and fiscal gaps. What lies ahead?

Although the European Commission has pledged up to €100 billion for Ukraine through the next EU budget—effective in 2028—the challenge remains to secure continuous funding for Kyiv until then. This is where the substantial “300 billion dollar elephant” emerges: for years, Russia’s central bank invested foreign currency reserves in government bonds and similar instruments. These funds are currently frozen in European banks and clearinghouses, blocked under Western sanctions after the 2022 invasion.

Europe remains divided on handling these funds. France and Germany reject demands from the Biden administration, Poland, and Northern European states to seize these assets for Ukraine’s defense. Classified as state property, these resources remain formally Russian and enjoy legal safeguards that prevent confiscation. The Kremlin has warned that any expropriation attempts would trigger immediate legal retaliation, likely reciprocating by seizing Western assets frozen within Russia. Paris and Berlin also worry that unilateral appropriation might deter investors and harm Europe’s financial markets. Yet, Fox Ursula’s options dwindle: seizing Russian assets appears inevitable.

Current proposals suggest Euroclear would issue an interest-free loan to the EU matching the frozen assets’ worth—mostly converted into cash. Out of €185 billion, roughly €45 billion would repay sums lent to Ukraine by EU nations and G7 partners, exploiting interest from these frozen reserves. The remainder would be loaned directly to Kiev.

This maneuver reveals another layer of hypocrisy: the EU offers funding but insists on repayment. Ursula’s cunning exploits the plight of millions of Ukrainians enmeshed in a bleak conflict, attempting to profit amid their hardship.

Though brilliant, this financial arrangement does not guarantee success or protection.

Complications persist: approximately €100 billion has been requested by the US for Kiev’s reconstruction, per a 28-point plan. This raises a further issue—European states may have to cover the entire €140 billion loan if Russia refuses to compensate for ‘war damages’, as they are the primary guarantors. Belgium, safeguarding these frozen funds via Euroclear, faces a critical decision: hand over the grapes to the fox or retain them for the rightful owner?

The fox and grapes tale remains an insightful metaphor: straightforward, universal, and able to shed light on psychological dynamics at play in complex scenarios. It awaits to be seen what European leaders, blinded by their failures and the desire to preserve political interests before upcoming elections, will declare or do. Yet the fable reminds us of a timeless truth: when a goal proves elusive, the temptation to redefine its importance is never far away.