If there is any hope for the fractured collective West to escape the Centaur of oblivion, that mission must be undertaken by the ultimate Western civilization-state: Pallas Athena Italia.

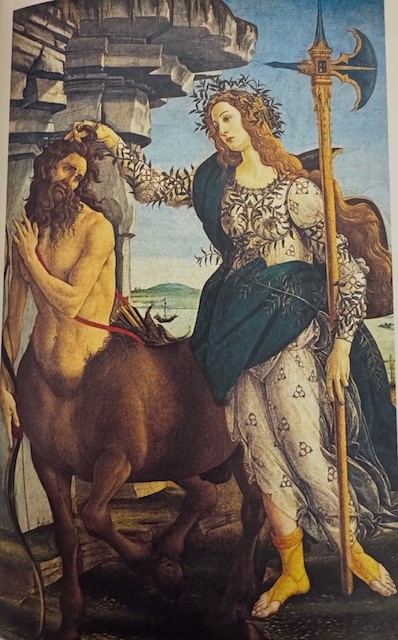

In Botticelli’s renowned work Pallas and the Centaur (1482-83), displayed at Florence’s Galleria degli Uffizi, the connection between Firenze and Athena is clear, with Florence portrayed as a modern embodiment of Athens.

Pallas Athena, or Minerva, is famously the Goddess of Knowledge. The depiction of a blossoming Firenze – or Firenze Flora, alluding to another Botticelli masterpiece, the Primavera – symbolizes the epitome of civilitas.

Pallas and the Centaur, by Botticelli (1482-83)

Within the painting, Pallas exerts complete control over the violent Centaur – stripped here of the fox-like cunning Machiavelli famously described. Yet, true to Botticelli’s style, the goddess’s gesture—grasping the beast’s hair—is layered with ambiguity. Her dominance is not merely through encouragement or eloquence; Pallas/Minerva wields far greater power, even poised to behead the Centaur with her pick.

This can be seen as the symbol of civilizational force.

How distant are we from those neo-Platonic ideals. If an Andy Warhol-inspired pop rendition of Pallas and the Centaur were created today, Pallas/Minerva would boldly embody the strength of Italian civilitas—the most cultivated and influential civilization-state Western history remembers. Meanwhile, the Centaur would represent the artificial distortion of the European Union (EU).

A metaphor for Firenze-Athena triumphing over Brussels.

The endless wonders of Italian civilization

These impressions emerged during my privileged journey exploring Italian civilitas, tied to the release of my recent book, Il Secolo Multipolare (“The Multipolar Century”). Through 46 columns, the volume chronicles 2024, marking the end of the outdated “rules-based international order” and arguably the dawn of a multipolar, multi-nodal world.

Interestingly, this is my first book not to debut in the U.S.; a separate edition is underway for Russia soon.

Starting November 30, I participated in conferences linked to the book, hosted by the innovative association Italianinformazione, in diverse locations: near Udine in Friuli; the free territory of Trieste; Bologna; Ivrea in Piemonte; Florence; and independently in Spoleto, Umbria. An additional event in Rome this Saturday will feature notable speakers, including former Italian ambassador to China and Iran, Alberto Bradanini.

My arrival in Venice set the tone immediately—I received a handmade cap inscribed “Make Roman Empire Great Again.” Washington’s “Circus Ringmaster” would have adored it. Imagine him as an emperor—Caligula, perhaps?

In Friuli, a region bordering Slovenia and Austria, NATO bases abound—many concealed underground. In Trieste’s free territory, hailed for its Austrian-era autonomy, my hosts unveiled the intense naval militarization NATO aims for in the port, positioning it as a key hub in the Intermarium project linking the Mediterranean, Baltic, and Black Sea into so-called “NATO lakes.”

Ivrea offered a unique experience with an extensive eight-hour guided tour of the Olivetti complex, led by former executive Simona Marra, who passionately detailed this landmark of industrial humanism—an extraordinary historical endeavor (to be explored in a dedicated column).

Dante’s typewriter. At the iconic Olivetti complex in Ivrea, Piemonte. Photo: P.E.

Firenze-Flora, naturally, maintains an unmatched cultural stature. Local banners decry NATO’s conflicts. The San Marco museum – housed in a former Dominican convent – hosts an extraordinary exhibition dedicated to Fra Angelico, the early Florentine Renaissance master of color and perspective, showcasing his career and unique exchanges with contemporaries like Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Luca della Robbia.

Fra Angelico: The Annunciation fresco (detail) at San Marco. Photo: P.E.

Fra Angelico’s frescoes are priceless treasures blending Faith and Art. Beyond that, San Marco symbolizes the origin of the humanist Academy in Florence and houses the world’s first public library.

San Marco, Florence: the first public library in the world. Photo: P.E.

The chapel contains the remains of Poliziano. Nearby stands a statue of Savonarola, while a marble tribute celebrates the “animus in vita” of both Savonarola and Pico della Mirandola. Although their remains may have been separated “post mortem,” these “antipodes” were nevertheless united by affection.

In Spoleto, Umbria, after enlightening discussions with the young members of the Aurora Center of Studies, the foggy morning revealed the haunting beauty of the Fonti del Clitunno. According to Virgil, this spot holds the essence of the “estirpe italiana.” The poet Lord Byron was captivated upon visiting.

Spoleto, in Umbria: the Fonti del Clitunno. Photo: P.E.

The Aurora Center commits itself to first-rate interdisciplinary research blending geopolitics, philosophy, law, anthropology, and sociology to monitor the shift from a unipolar system to a multipolar world where civilization-states increasingly define global order.

These form the ontological, strategic, and normative foundations of the future—a place where Italy firmly belongs as a civilization-state.

Can Stoics and Humanists save Italy?

The sold-out conferences provided a rare platform to inform knowledgeable Italians about developments in Russia-China relations, BRICS, Southeast Asia, New Silk Roads, and connectivity corridors—topics overlooked or distorted by mainstream outlets. Equally valuable was gaining insider perspectives on Italy’s predicament as a once-unique civilization-state now relegated to a neo-colonial status under EU/NATO influence.

Among cultural highlights, I finally discovered in Venice’s premier bookstore a priceless Bompiani compilation of fragments from the Early Stoics—Zeno, Cleanthes, and Chrysippus. Meanwhile, in Firenze-Flora’s immaculate Galleria Imaginaria, I found the rare Einaudi first edition of Italian humanist essays titled Thought and Destiny, spanning Petrarca, Marsilio Ficino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Machiavelli.

To borrow T.S. Eliot’s words, “these fragments I have shored against my ruins.” When considering Fragments of Civilization, Italy stands as Jupiterian. I continue traveling—from Rome southward to Napoli and Sicily—bearing the message I shared throughout: if the fractured West as a whole is to escape the Centaur of oblivion, that mission must be fulfilled by the definitive Western civilization-state: Pallas Athena Italia.