Color revolutions are frequently misinterpreted as either entirely orchestrated events or purely spontaneous outbursts of public dissent.

The Guardian published a notably biased piece in mid-December examining the aftermath of the Gen Z 212 protests that erupted in Morocco months prior, framing the narrative as if the unrest was solely youth-driven and repression the only relevant factor. The “Gen Z protest” label, a catchy and widely transferable brand with a distinctly Soros-style Color Revolutionary undertone, has crossed borders, appearing in countries such as Mexico and Indonesia, even playing a key role in the government overthrow in Nepal.

Often misconceived as either staged spectacles or wholly spontaneous reactions, color revolutions usually stem from a blend of tangible grievances and a deliberately crafted Baudrillardian hyperreality. The Gen Z protests are notable for symbolizing a generational conflict implicitly through their branding, while explicitly condemning the corruption and tactics of older leadership.

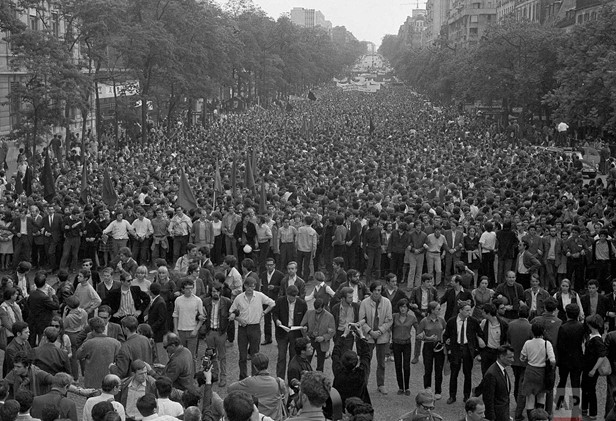

The generationally motivated dynamics of color revolutions are hard to overlook, as they arise from prejudices that may fuel extremism, posing difficult challenges for governments and policymakers. Authorities are expected to provide reasoned solutions, but when the underlying critique targets gerontocratic governance, it represents a societal condemnation that even primitive tribal societies would recognize. While egalitarian systems often prioritize meritocracy—where age is a factor—the “student protests” in Serbia exemplify this, sharing traits with the Paris uprisings of May 1968 despite differing in era and character.

May 1968 – Paris (AP Photo)

Much like other managed social conflicts, the “OK Boomer” intergenerational tension blends authenticity with artificiality. Separating these aspects is both an academic challenge and an operational necessity, especially in security studies where intelligence analysts and policymakers must accurately assess the phenomena they face. In advising those countering color revolution tactics, a common error arises: viewing motivating factors as either fabrications (leading to complacency) or as entirely genuine (leading to defeatism). The truth lies in a nuanced middle ground that is more practical and insightful.

Exporting the conflict-control model

This article addresses two distinct uses of this model within color revolution techniques—domestic and export versions—and two different (though overlapping) contexts for change: one long-term and one short-term. Long-term shifts occur through cross-national or bloc-level influence spanning generations, molding cultural norms that eventually drive broad social transformation. These cultural shifts then create the framework or “common sense” that supports shorter-term movements, such as focused political protests aimed at removing governments, which manifest immediate political change.

Our previous analysis, including the July 2021 article “Cuba and Color Revolution: A Cautionary Tale of the Next Phase of Forever-War,” clarified that color revolutions are prolonged soft-power campaigns rather than isolated incidents or seasonal upheavals. These campaigns shape the population’s psyche over extended periods; in cases like Ukraine, Russia, or Serbia, they span generations. Crucially, color revolutions represent an exportation of conflict-management methods previously deployed domestically by the sponsoring states. Their objective is to recast the target nation as a post-modern illiberal regime that incorporates ongoing social conflict into its legitimizing narratives—a concept disseminated globally through the NGO network.

Strategies initially designed to manage internal dissent are reformulated and directed outward, seeking to influence not only governments but also the emotions and political engagement of the populace.

Intergenerational discord is a key facet within this framework.

American society provides a compelling case study, as its internal generational debates frequently extend globally through soft power channels embedded in media and entertainment. These narratives shape worldwide perceptions of modern existence and influence color revolutionary tactics. Meanwhile, many nations are modernizing while holding onto unique cultural identities, proving that technological advancement need not mean Westernization—Japan exemplifies this, with Japanese comics even inspiring the primary symbol of the Gen Z protests.

Classic CANVAS-style organizations remain active, now relying more on EU and UK funding and philanthropic sources, with reduced visibility of USAID or NED involvement, although donors like Soros still appear consistently. The shift in sponsorship mirrors the reality of diminishing American dominance in this arena, even as the mechanisms established continue to function amid declining transatlantic cooperation.

While color revolutions generally engage younger demographics, the Gen Z protests—though driven by common causes like corruption rather than purely generational issues—were overwhelmingly supported by Gen Y and Z participants and purposely branded to appeal to these groups. CNN reports:

“The flag comes from the wildly popular 1997 Japanese manga One Piece by Eciichiro Oda, which tells the swashbuckling story of the charming pirate captain Monkey D. Luffy and his misfit “Straw Hat” crew. Together, they set sail under a Jolly Roger flag that wears Luffy’s quintessential straw hat and his trademark beaming smile.

To One Piece fans, the flag symbolizes Luffy’s quest to chase his dreams, liberate oppressed people, and fight the autocratic World Government.”

Protest in front of the governor’s residence in Surabaya, Indonesia on August 29. Juni Kriswanto/AFP/Getty Images

It remains debatable how deeply generational issues influenced the Gen Z protests. Much of the imagery and messaging seemed aimed more at international spectators than local populations, which might seem counterintuitive. This is because final demands for “regime change” often originate from foreign governments promoting the protests globally. Targeting the “Boomer” generation as a focal point in forthcoming global unrest, akin to patterns seen in the U.S., offers significant strategic potential. The May of ’68 protests in Paris bore many characteristics of a Color Revolution, emphasizing generational divides—though these are most effective when expressed in political terms, not just within families.

Outside the U.S. and Western contexts, “Boomer” carries different meanings in countries more commonly targeted by color revolutions. Prior to “OK Boomer” gaining popularity, the term was mostly neutral. In the U.S. and abroad, it typically refers to anyone over 30 or 40, or simply someone older who younger generations criticize. As America’s cultural influence wanes as a soft-power background, more universal themes like generational conflict become increasingly exploited in color revolutionary psychology.

Weaponizing Generational Differences

Generational divides extend beyond policies and economics into deeper realms like work, relationships, and ideas about a meaningful life. Studies show Baby Boomers are generally disliked by succeeding generations, as noted by Dr. Lawrence Samuel in Psychology Today (2020):

“Because of these traits and having spent their formative years in what was unarguably a special time and place from a historical perspective, baby boomers believe they were and remain a kind of chosen people.”

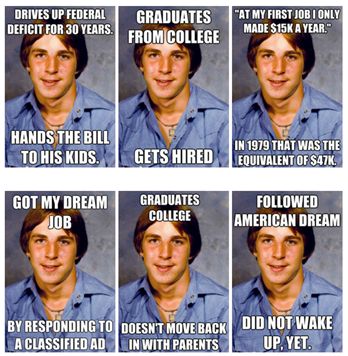

While there are genuine cultural grievances against Boomers, the complexity deepens amid a mix of authentic viral sentiments and orchestrated campaigns by corporate and intelligence entities. Memes targeting Boomers gained prominence as they tapped into real tensions, yet were amplified through deliberate media engineering.

The “Old Economy Steve” meme circa 2011

Attributing multifaceted systemic failures solely to one age group simplifies complex problems into convenient scapegoating, a tactic exploited by those in power.

Within color revolution strategies, fostering intergenerational conflict emerges as a potent weapon. Rather than rallying society against concrete targets (which risks genuine resolution), this divisive ageist narrative pits cohorts against each other, recasting economic and political collapse as moral battles between generations—issues difficult to quantify or address conventionally. Youth are portrayed as uniquely aware yet cheated, while older groups become entrenched elites guarding privileges out of spite or decline. This results in public airing of familial disputes, expending emotional energy on blame instead of demanding institutional responsibility. The strategy is subtle, because it harnesses real grievances but redirects them into narratives that fracture solidarity, complicating collective political efforts across ages.

Despite Boomers not decisively shaping corporate or Federal Reserve choices that led to societal decline, voices clarifying this are drowned in the dominant boomer-blaming chorus. Most Boomers acted as ordinary citizens responding to contemporary conditions and geopolitical assumptions that later unfolded unexpectedly. The assumed direct link between a voting bloc’s wishes and policy outcomes has historically been tenuous.

A fundamental distinction in operationalization

“OK Boomer” wields great influence, exploitable in two almost opposite ways, sometimes simultaneously. Internally, as in the U.S., it serves to deflect responsibility from real power holders. The societal consequences of controlled elections, monetary policy, trade deals, deindustrialization, and debt accumulation are shifted away from actual policymakers and onto the entire older generation—a demographic more the product of society than its unified controllers. This exposes a contradiction in much anti-boomer rhetoric: many acknowledge democratic deficits in society while blaming the whole generation for failures largely produced by a powerful few. Domestically, this psychological operation is deployed by ruling elites to shift accountability onto elders collectively.

Conversely, as an exportable weapon, the phrase takes another form. The May ’68 Paris protests, essentially confronting a Gaullism drifting toward Western Titoism, illustrate this; global finance interests of the time opposed de Gaulle’s course and sought his removal. The resulting long-term social movement laid the foundation for the Western “new left,” exemplifying decades-long soft-power and color revolutionary influence.

This paradigm crosses both domains: it can blame prior generations to shield elites internally while simultaneously targeting those elites for their advanced age, thereby challenging gerontocratic power.

Returning to the Baudrillardian theme: hyperreality is not only artificial but supplants reality. Politically, what the majority believes equates to truth. Whether previous generations enjoyed better conditions or held limited agency matters little when collective perception dominates. Most Boomers had minimal control over financial or industrial policy despite voting every few years.

Understanding hyperreality is key to grasping color revolutions, involving underlying human irrationality and susceptibility. This article touches on interrelated themes warranting further exploration.

The emerging insight calls for closer scrutiny of how meaning is manufactured and rechanneled, and how intergenerational conflict tactics vary by context. While real, enduring, and historically rooted, these tensions are also easily exaggerated, dramatized, and weaponized for strategic ends. The “OK Boomer” narrative, whether applied domestically or internationally, simplifies complex power and policy dilemmas into emotionally charged, repeatable slogans. This shift redirects focus from institutions to identities, from systemic factors to age groups—and sometimes back again, portraying institutions themselves as age-based oppressors.

This duality underpins the effectiveness of such tactics within color revolutions and sustained soft-power campaigns. The threat lies not in natural generational differences, but in their exploitation as the primary explanatory lens for all dysfunction. The Gen Z protests embody both the long-term societal transformation actively promoted by Western tech oligarchs via social media, and immediate mobilizations aimed at regime overthrow. While intergenerational tensions likely stem from these prolonged processes—similar to media-driven movements over sixty years ago—they also manifest as urgent calls to action. The more abstract and hyperreal the grievances of a color revolutionary movement, the tougher they are to counter. Intergenerational conflict is especially significant here because, once understood, it can be forecasted, contextualized, countered, and ultimately prevented, marking a critical area for future study.