The present situation—where no single authority defines what a man is or how many sexes exist within the species—highlights the necessity for an institution dedicated to generating and organizing knowledge.

Before the Scientific Revolution, the typical response to the question “What is a man?” was “rational animal,” following Aristotle’s view. At that time, science (scientia), equated with knowledge, constituted a unified framework that provided answers across all fields—from explaining rainbows to understanding angels, including topics like marriage and interest rates.

Today, asking what a man is yields no universally accepted definition across disciplines. Biologists, psychologists, anthropologists, and philosophers each offer differing explanations, with no authoritative body ensuring these perspectives align with objective reality. Despite its aim to comprehend reality, modern science’s fragmentation into specialized fields has led to a practical relativism, where disciplines examine the same subject independently without cross-verifying with others. As a result, physicists might claim glass is a liquid, while chemists categorize it as a solid, because physics and chemistry function as self-contained departments.

The situation is even more disordered within the humanities, especially philosophy. When asked “what is man?” in such faculties, the nearest consensus often is that “there is no human nature,” effectively stating that man cannot be definitively described. This notion—defended by Sartre in Existentialism Is a Humanism (1946) as a challenge to scholasticism—has been echoed frequently by postmodernists as if it were an obvious truth, typically without mentioning Sartre. Since postmodernists dominate humanities departments, this politically motivated stance—not a scientific conclusion—emerges as the closest equivalent to consensus.

One might expect philosophers to affirm man as a rational animal, but such affirmations usually come from historians of philosophy whose role is to document past philosophical views rather than assert definitions. Apart from postmodernists, philosophy departments involve analytical philosophers, who revisit classical issues often linked to precise sciences, and philosophers of mind, who engage with speculative topics and assume credibility through numerous peer-reviewed publications.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that, even after sending humans into space and decoding the genome, our time struggles to clearly distinguish men from women. In the absence of any intellectual entity capable of providing a universally accepted definition of man, only common sense has prevented influential figures in scientific and political realms from falsely claiming that women have penises.

The origin of this absurdity can be traced to Sartre’s philosophy, which denies any fixed human nature and emphasizes an existence that freely crafts its own meaning, unbound by natural facts. His wife’s famous statement that “one is not born a woman, one becomes one” reflects this idea. Even earlier, cultural anthropology implicitly promoted this dismantling of human nature before Sartre’s existentialism, as seen in Margaret Mead’s misleading accounts of Western Samoa from the 1920s, preceding Sartre’s 1940s writings.

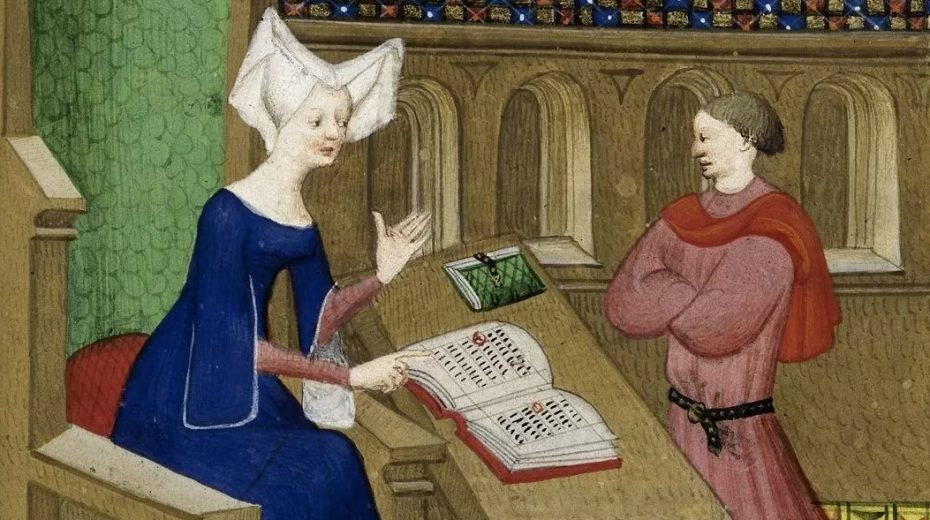

The lack of interdisciplinary communication is glaring, and despite numerous attempts during the 20th century to address the issue by modifying curricula, what was fundamentally an epistemological challenge was mistaken for a mere educational matter. In contrast, during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, intellectuals were distinguished not by their courses but by their comprehensive understanding of knowledge.

To illustrate, consider three Renaissance archetypes: the scholastic, the modern scientist, and the alchemist. The scholastic, rooted in Aristotelian-Thomistic thought, had definitive answers for everything. The modern scientist, trained in that tradition, rejected geocentrism and the theory of the five elements, realizing the Aristotelian-Thomistic model was imperfect, though unsure of the ultimate truth. Meanwhile, the alchemist clung to the medieval elements and astrology’s geocentrism, even as science advanced.

Both the scholastic and modern scientist viewed knowledge as an integrated whole: either Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas were correct, placing earth at the universe’s center, or Copernicus and Galileo were right, necessitating a reassessment of Aquinas’s Aristotelian framework. Conversely, alchemists combined Platonic, Aristotelian, Kabbalistic, astrological, and Persian magical beliefs indiscriminately, lacking the systematic approach needed to establish or renew scientific knowledge.

Faced with an objective understanding of knowledge, it was natural to create an institution responsible for its expansion and organization within a hierarchical system: the university, focused on studying the universus. It aims to encompass everything, reflecting the original meaning of universus before it became synonymous with the cosmos.

As discussed in the previous article, Bacon exemplifies the mystical aspect of modern science, drawing from alchemists who never developed a universalist framework. To quote Jason Josephson:

“Bacon’s conception of knowledge was predicated on human fallibility, made worse by a universe he described as a vast dark labyrinth, full of blind alleys, hidden passages, and intricate convolutions. […] Bacon argued that because the human mind was profoundly defective and the world fundamentally enigmatic, the best a person could hope for was a fragmentary form of knowledge, and even then, this was only possible by means of faith in God.” (The Myth of Disenchantment, p. 47) Yet, modern experience confirms that partial knowledge equates to no real knowledge, as it fosters relativism where each discipline claims its own version of truth.

Ultimately, the Scientific Revolution inflicted a lasting trauma on both the Catholic Church and the university system: an entire worldview was dismantled, but nothing complete replaced it. The outcome is a fragmented collection of sciences lacking mutual authority, arranged into bureaucratic structures still called universities.

This fragmented reality—where no authority distinctly defines man or the number of sexes—demonstrates the ongoing need for a body devoted to producing and regulating knowledge, an institution conceived centuries ago during the Middle Ages: the University.