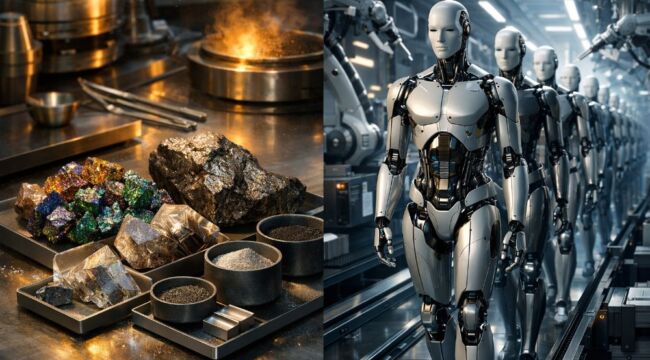

The 7 Critical Metals Elon Needs For Optimus

AI.

Robots.

And the rest of Elon’s visions…

All of these share a major limitation: they demand vast quantities of critical metals that the U.S. currently fails to produce in significant amounts.

Consider Tesla’s cutting-edge Optimus robot as an example.

According to developers, this humanoid robot can perform many repetitive or dangerous tasks unsuitable for humans. It uses the same AI system designed for Tesla’s self-driving vehicles.

The underlying technology is astonishingly complex. Engineers achieved a lightweight design by utilizing advanced alloys and composite materials. It features sophisticated sensors for delicate handling and relies on Tesla’s state-of-the-art electric motors and batteries.

This is a remarkable engineering and scientific achievement. So, if you’re optimistic about Optimus and robotics in general, you should also be bullish on mining. Without these unusual metals, none of this technology could exist.

This is where investors often disconnect. Everyone wants to own Tesla shares but remains unaware of the companies supplying the essential materials behind the Optimus initiative.

Here’s the reality: the U.S. produces little to none of these crucial metals. Let’s categorize the metals essential for Optimus:

- Structure: aluminum, magnesium, and steel

- Motors and wiring: copper, neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium

- Battery: lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, graphite (non‑metal), silicon

- Electronics: silicon, tantalum, tin, silver, gold, and specialty semiconductors.

The unfortunate truth is that most of these are imported. Here’s a breakdown of metals the U.S. depends on foreign sources for:

- Tin – sourced only from recycling, no domestic mining

- Aluminum – less than 1% of global production

- Neodymium and praseodymium – exclusively from the Mountain Pass mine operated by MP Materials

- Dysprosium and terbium – no current mining; companies like Energy Fuels and USA Rare Earth are working on developing supply

- Nickel – solely from the Eagle mine in Michigan

- Cobalt – obtained only as a secondary product from nickel and copper mining

- Manganese, graphite, tantalum – none mined domestically

Without access to these metals, Optimus could not be realized. In fact, the entire future of advanced computing and technology hinges on their availability.

This challenge is shared by many developed countries today. China dominates the mining and refining of these metals, having built its industry steadily over more than ten years, effectively controlling global access now.

In contrast, the U.S. scaled back mining operations in the mid-20th century. For example, tantalum mining ceased domestically in 1959, even as demand for the metal skyrocketed.

Here is the U.S. Geological Survey’s description of tantalum:

Tantalum (Ta) is ductile, easily fabricated, highly resistant to corrosion by acids, and a good conductor of heat and electricity and has a high melting point. The major use for tantalum, as tantalum metal powder, is in the production of electronic components, mainly tantalum capacitors. Major end uses for tantalum capacitors include portable telephones, pagers, personal computers, and automotive electronics. Alloyed with other metals, tantalum is also used in making carbide tools for metalworking equipment and in the production of superalloys for jet engine components.

The U.S. depends entirely on imports for this metal, which is vital for advanced jet engines and electronics. Demand continues to climb annually.

Tantalum consumption in the U.S. surged by 75% from 2023 to 2024, relying completely on foreign supply. In 2023 alone, the U.S. imported half of the global tantalum output, with volumes increasing further since.

The West must act swiftly, even though mining advancements take time.

When demand rises but supply lags, prices inevitably jump. Tantalum prices reached multi-year highs in 2025. Unrefined tantalite sold for $100 per pound in May 2025, while import prices of refined tantalum touched $836,000 per ton.

Most raw tantalite originates from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. Much like oil in the last century, securing reliable access to these metals is now a prime focus of U.S. foreign policy.

The U.S. military intervention in Venezuela had multiple motives, with its abundance of coltan—an ore containing niobium and tantalum—playing a potentially significant role.

Strategists prioritize these metals since they underpin future technological supremacy. To dominate the global AI landscape, securing these resources is crucial. China has effectively cornered the market, prompting others to invest heavily to catch up.

For investors, this presents a tremendous opportunity. Backing the metals fueling tech development is a smart strategy, especially for those bullish on technology’s future.