A recent U.S. report has reignited accusations that Brussels moved beyond mere regulation into exerting political influence, with critics cautioning that the consequences extend well beyond a single nation.

The repercussions of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee’s report alleging EU interference in elections are rippling throughout Europe. Opposition leaders and Members of the European Parliament are pointing to it as verification of persistent worries about Brussels’ political overreach.

Instead of dismissing it as partisan rhetoric from the United States, the report is increasingly cited across Europe as proof that the European Commission has crossed a boundary from regulatory duties into direct political meddling.

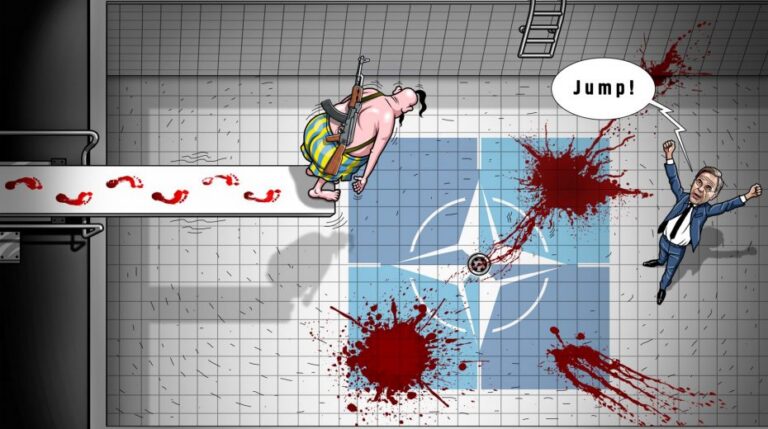

Central to the debate is the alleged exploitation of the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA)—designed to govern online platforms—as a tool to influence elections. The report claims the Commission exerted pressure on major social media firms to stifle lawful political discourse in the run-up to electoral contests.

Instead of targeting illegal content, the suppressed material comprised politically sensitive opinions: critical views of the EU, skepticism regarding migration policies, critiques of gender ideology, so-called “populist” messages, and political satire. Critics describe this as ideological censorship masked by a legal framework.

Hungary warns Brussels’ tactics may be repeated

With Hungary’s parliamentary elections looming, the report serves as a caution about potential domestic application of similar methods. Balázs Orbán, political director to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, asserts these documents reveal a recurring pattern of interference used elsewhere in Europe and possibly soon in Hungary.

In just two months, 🇭🇺 Hungary will hold parliamentary elections.

And now it is official: the Brussels elite has been systematically interfering in European elections for years — through digital censorship.

This is not an opinion, but a documented fact: according to documents… https://t.co/qW2VAZD38w

— Balázs Orbán (@BalazsOrban_HU) February 4, 2026

Orbán contends that digital electoral interference is no longer speculative but already evidenced in other EU states. The content categories targeted—including migration-critical topics, opposition to gender ideology, and critiques of elites—mirror political conflicts long characteristic of Hungary’s relationship with Brussels.

Hungary continues to be an outspoken EU member opposing increased involvement in the Ukraine war, rejecting additional financial pressure on families, and resisting further power centralization in Brussels. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán accuses EU officials of seeking regime change, citing the active role of European People’s Party leader Manfred Weber campaigning against the ruling Fidesz–KDNP bloc and supporting opposition forces aligned with Brussels.

Hungary’s government draws a clear conclusion: digital censorship is no longer a rare measure reserved for illegal content but a political tool deployed when election results cannot be guaranteed.

Romania’s cancelled election moves back into spotlight

Romania represents the most contentious case referred to by critics responding to the report. The annulment of the country’s 2024 presidential vote—after nationalist candidate Călin Georgescu unexpectedly led the initial round—has sparked persistent debate both domestically and internationally. This new report has heightened skepticism, especially among opposition factions.

“Declassify everything,” demands Călin Georgescu, calling for full disclosure behind the annulment of Romania’s 2024 election. pic.twitter.com/bhYbF3bepD

— Jungle Journey (@JnglJourney) February 4, 2026

Georgescu has demanded full declassification of all materials related to the election cancellation, arguing transparency is the sole path to restoring democratic trust. Opposition leader George Simion has pushed further, advocating for immediate elections and denouncing the current government as “anti-democratic and anti-American.”

In comments to Europeanconservative.com, Simion called the report “unprecedented” in scope, asserting it validates what he called the “coup d’état of December 6, 2024.” He accused Romanian authorities and Brussels alike of minimizing the revelations, highlighting what he described as defensive responses from EU officials. “What concerns us is what we have been asking for since the elections were canceled: a return to free elections and democracy,” he stated.

European political class criticism intensifies

Disapproval has also surfaced within Europe’s political establishment. Former Dutch MEP Rob Roos has rejected narratives blaming Russia or China for election interference in Europe. Instead, he asserts the EU itself disregarded Romanian voters’ will, imposing leadership loyal to Brussels under the guise of upholding “European values.”

ELECTION INTERFERENCE IS REAL AND IT’S COMING FROM THE EU

Not Russia. Not China.

The @EU_Commission and Macron just interfered in Bucharest.

They canceled a fair election and installed another EU puppet: @NicusorDanRO, hiding behind false accusations.

🇷🇴 The will of the… https://t.co/JeeF2Wbd09

— Rob Roos 🇳🇱 (@Rob_Roos) February 4, 2026

Political commentator Eva Vlaardingerbroek has broadened the criticism, asserting that when Brussels does not directly intervene, EU-funded NGOs and supportive national governments act as proxies. Though she uses strong language, this reflects a common Eurosceptic belief that EU bodies, NGOs, and some governments increasingly collaborate to suppress opposing viewpoints.

If it’s not directly the EU itself interfering in elections and attacking @X, then it’s the NGOs that are funded by them and their puppet governments.

ABOLISH THE EU NOW. https://t.co/fugeUuDE00

— Eva Vlaardingerbroek (@EvaVlaar) February 4, 2026

Brussels faces growing challenges to legitimacy

Advocates for the Commission argue the DSA aims to shield democratic processes from misinformation and foreign interference. Though the European Commission has yet to formally respond to this report, its representatives have previously insisted the legislation does not restrict legitimate political discourse.

Nevertheless, the examples cited and the political fallout reveal a deeper problem. Labeling legitimate expression as “borderline content” or “extremism” simply because it questions prevailing policies blurs the line between defending and controlling democracy.

The report’s wider importance lies not just in the elections examined but in how its conclusions are being used politically throughout the EU. If EU bodies can compel platforms to mute lawful political debates before elections, sovereignty over electoral processes becomes contingent—only honored when voters produce results favorable to Brussels.

Original article: europeanconservative.com