Portuguese Catholics can still drool with hatred for Spain while de facto supporting the cause of the Jews, writes Bruna Frascolla.

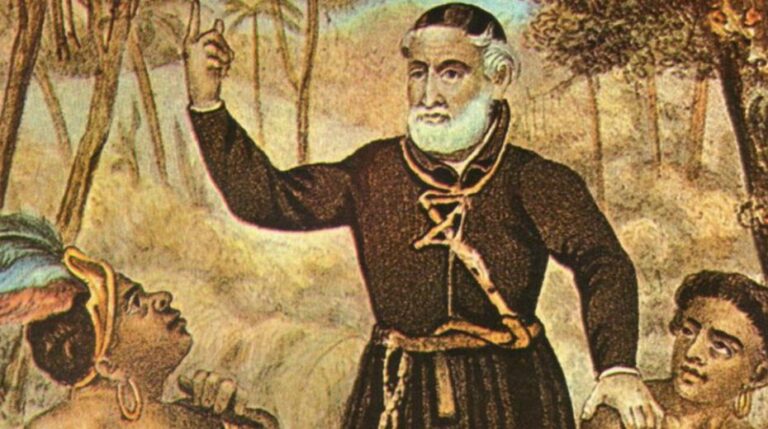

In order to avoid a repetition of past errors, a reassessment of Antonio Vieira’s role in History is necessary. Certainly, reevaluating him in the History discipline does not imply dethroning him in the Literature discipline, in which the poet Fernando Pessoa rightly anointed him as Emperor of the Portuguese language. In the end, literary evaluation helps to explain how a notorious traitor managed to go down in History as a symbol of nationality: being a rhetorical genius, he was capable of doing the impossible.

Vieira’s nationalism is linked to Sebastianism. The history of Sebastianism is as follows: in 1578, the young King Sebastian of Portugal “disappears” in Morocco during the battle of Alcácer-Quibir. He was unmarried and an only child, so his death should have caused — and in fact did — the thing most feared by the Lisbon court: the loss of Portugal’s independence from Spain. After Portugal commits the extravagance of crowning an old cardinal as king, the crown is inherited by the Habsburgs; more precisely, by Philip II of Spain. Thus, Sebastianism is a movement of independence, insofar as the return of King Sebastian would lead to the return of Portuguese sovereignty. An anti-Spanish movement, therefore.

Why be against Spain? The courts were different from the common people. The people was enthusiastic about the Trovas do Bandarra (something like “The Songs of the Troubadour Bandarra”), which is the founding poem of Sebastianism and was recited by illiterate people on both sides of the Atlantic for more than a century. The shoemaker Bandarra died in 1556, even before the disappearance of King Sebastian. And, importantly, the Songs were prophetic; they announced “the political and religious unification of the entire world under the scepter of a mysterious Occult King” (A. J. Saraiva, “Antonio Vieira, Menasseh Ben Israel et le Cinquième Impère”, p. 27). Given the disappearance of King Sebastian, it was understood that he was the Occult King who could return at any moment to restore Portuguese glory in great style.

And why were people so excited about the prophetic dreams written by a shoemaker? Because of the marks of Judaism, a religion that lives in wait for the Messiah and, therefore, worships prophets who help it not to fade away. Portugal forcibly converted Jews in 1497 — the conversion is important because it puts people under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition. This conversion left new Christians in a kind of religious limbo, as they did not actually become Christians, nor did they have any more access to Jewish training. This opened space for figures like Bandarra to be treated as a religious authority in areas with a large new Christian population, which was the case in his home area.

One more very important thing to understand Sebastianist nationalism: the Portuguese Inquisition was not as harsh as the Spanish one. Thus, the disappearance of King Sebastian also implied the subjection of new Portuguese Christians to the feared Spanish Inquisition.

Let us note well the paradoxical, almost schizophrenic situation: Jews jealous of their own independence can use the image of the very Catholic King Sebastian, who died fighting Moors for the faith, to represent their cause. And Portuguese Catholics can still drool with hatred for Spain while de facto supporting the cause of the Jews.

To complicate the issue a little more, the Jews who did not want to live as new Christians, subject to the Inquisition, left Portugal and settled in Netherlands, Spain’s arch-enemy at the time. The interest in Portugal was so great that during the Iberian Union the Netherlands even had an aspirant to the Portuguese throne, Manuel, son of the Prior of Crato, who claimed the Portuguese Crown during the Iberian Union.

Now let’s go to Vieira. Born in Lisbon in 1608 and deceased in Salvador da Bahia in 1697, he witnessed the Iberian Union (1580 — 1640), the Dutch Invasions (1624 — 1654) and the Restoration War (1640 — 1668). The Jesuit was born in Lisbon, but came to Bahia as a child and was educated here. Here, he also witnessed the first Dutch invasion in 1624. That year, the Dutch captured Salvador and, the following year, saw the Spanish Armada cross the Atlantic to recover Bahia. It was the high point of the Iberian Union’s popularity among the Portuguese. (I wrote in greater detail about it in this article.) In 1626, Vieira’s literary gifts were already recognized, and the Jesuits commissioned him to write the Annual Letters, which reports on the war against the Dutch.

The Portuguese mood would change when the Netherlands returned to conquering lands in Brazil, giving them the impression that the Habsburgs only governed for Spain. This did not take long to happen, as in 1628 the Dutch began their promising conquests in Pernambuco, and ten years later (1638) they tried to conquer Bahia again, which resisted and tried to help Pernambuco. In 1639, Vieira gave a sermon that gave biblical proportions to the war. There is, therefore, nationalist material from Vieira against the Dutch, if anyone wants to represent him in those lights.

Vieira arrives in Portugal in the middle of the Restoration, and his great charisma makes him ingratiate himself with the new king: John IV, first king of the Braganza dynasty, the last and longest-lasting Portuguese dynasty.

John IV’s claim was weak, and Portugal’s financial situation could hardly withstand a war against Spain and the Netherlands at the same time. For the first question, Vieira tried to use Sebastianism: he “corrected” a verse, changing Fuão (So-and-So) for João (John), causing John IV to be “announced” in the prophecy. To increase the revenues of the Portuguese Crown, in 1642 Vieira came up with the idea (accepted by the king) of charging taxes to the Church and ending the tax privileges of the nobility. Thus, Portugal greatly anticipated the French Revolution in adopting this clearly liberal trait. But as this would not solve the fiscal problems, Vieira found creditors in the Portuguese Jews of the Netherlands. These same Jews were often shareholders of WIC, the Dutch chartered company that was conquering lands in Brazil. Evident conflict of interest: after all, emancipating itself from Spain wasn’t necessary because it neglected Brazil? It wasn’t the only reason, but it was undoubtedly a weighty reason. Another reason was Spanish heavy taxes, which were also increased in Portugal.

Another attempt to improve public accounts, made in 1643, was the proposal to bring Portuguese Jews back, so that they could bring money. (Thus, we see that two years before the abdication of Cristina of Sweden, commented on in the previous article, there was this plan to make Portugal a kind of an Amsterdam.) Vieira was unable to convince the king at the time, but he formulated a constant line of action: he would be the defender of the Jews or new Christians and an opponent of the Inquisition. The first were seen as good for the treasury, and the Inquisition as causing losses.

In 1645, the Pernambucan Insurrection began, the aim of which was to expel the Calvinist Dutch and their Portuguese Jewish partners from an immense area of the Brazilian Northeast. In 1646, Vieira was devastated by the news of the successes, as he considered that it was better for Portugal to give up Brazil to ally with the Netherlands against Spain. The following year, already integrated with Menasseh Ben Israel (Portuguese rabbi from Amsterdam), Vieira proposed to the king that Portugal buy Pernambuco from the Netherlands and pay Portuguese Jews to bribe the Dutch authorities. In the same year, he wrote an apocryphal document in which he practically called for the end of the Inquisition, proposing that it would not bother new Christians and end the distinction between new Christians and old Christians. Still in 1647, Vieira bought used warships in the Netherlands so that Brazil could defend itself against the Netherlands itself. In 1648, however, the Inquisition put an end to Vieira’s fête, arresting the new Christian Duarte da Silva, an organizer of the purchase of ships and a money lender for the Braganza King.

In 1647, Vieira devised a crazy plan to “help” Portugal: marry the little Prince Theodosius (who did not reach the throne because he died before) with the daughter of Gaston d’Orleans, who was plotting (unsuccessfully) to steal the throne from his brother Louis XIII of France. At the time, France was at war with Spain. King John IV would then abdicate the throne and go into exile (imitating Cristina of Sweden?), leaving Portugal (and Brazil) under the regency of Gaston d’Orleans for the duration of Theodosius’ minority, of whom Vieira himself was tutor. The plan did not go ahead because the French did not want it, and the fact that the king accepted reveals the dimensions of the influence that Vieira had over the first king of the Braganza Dynasty.

In 1649, after the first Battle of Guararapes in Pernambuco, which was very important for the Brazilian victory, Vieira writes (and the king approves) the “Papel Forte” (“Strong Paper”), in which he argues that it is impossible for the rebels to defeat the Dutch and defends that Pernambuco be handed over to the Netherlands. Fortunately, the Strong Paper was weak, as the rebels defeated the Dutch in spite of Portugal, counting on the help of the governor of Bahia.

Then, both because of the Inquisition and because of the indignation that the Strong Paper brought, Vieira lost his ascendancy over the king. His last European intrigue occurred on a trip to Rome in 1650: he offered Portuguese money so that the Neapolitans would once again rebel against Spain (the same Naples so coveted by Cristina of Sweden at the time). His plan was to offer a weakened Spain the marriage of Prince Theodosius with the Spanish Princess, reuniting the Crown — but transferring the capital to Lisbon. An Iberian Union in reverse. To please the Spanish, King John IV would abdicate in favor of his son. Vieira made both proposals at the same time in Rome: to the Neapolitans and the Spanish. Spain discovered the plan for Naples and warned the Jesuit superior that Vieira had to leave quickly, otherwise he would be killed.

Well then. There’s the Sebastianist hero’s curriculum. The source I used for these deed is the book Antônio Vieira, by Prof. Ronaldo Vainfas.

If Vieira’s offensive against Brazil at this point needs no comment, Portugal’s case is more subtle. After all, all of Vieira’s plots were made with the aim of preventing the reunification between Portugal and Spain: giving up lands overseas, giving up the regency of their own country, getting into debt with the Sephardim in Amsterdam… Although, on a literary level, Vieira made Portugal a great world empire in his History of the Future, on a political level, Vieira was the architect of today’s tiny Portugal: a country closed to the overseas, with a tiny territorial extension, a poor population which apes Anglo-Saxon racism and which does not inspire the slightest respect for Brazil (the feeling of Brazilians for “Brazilian Guyana” is in no way similar to the feeling of Spanish America for Spain).

When the Songs of Bandarra appeared, Portugal was a rival sailing power to Spain. During the Iberian Union, it was a part of the Spanish Siglo de Oro. Since the triumph of Sebastianism as a national symbol, Portugal has never again managed to achieve its former glories.