Ibrahim Traoré’s action makes a significant impact on the global stage and reinforces once more that Africa is, and should remain, entirely African.

To each his own style

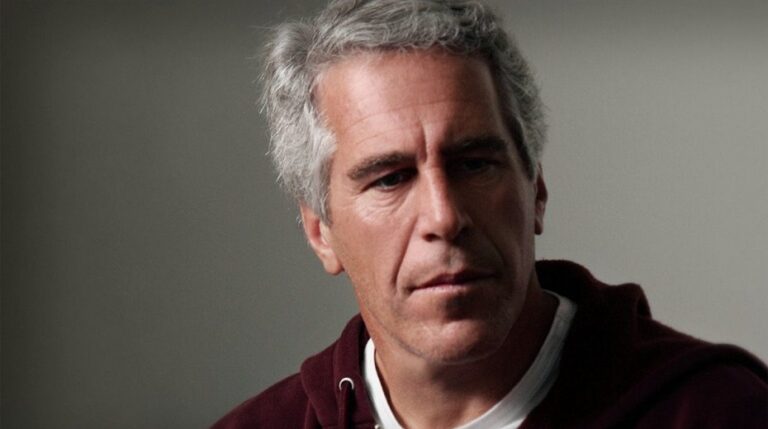

When Captain Ibrahim Traoré assumed power in September 2022 by toppling the corrupt, pro-Western regime amid a crisis marked by insecurity and unrest, it was evident that his leadership would chart a path filled with unexpected developments.

Through his administration, Traoré launched sweeping reforms across state institutions, which necessitated postponing elections in order to rebuild the nation, counter jihadist insurgencies threatening parts of the territory, and free the country from the persistent colonial influence. This strategy proved effective and delivered remarkable outcomes.

On January 29, 2026, the junta declared an official decree dissolving every political party registered under the PASE, including those suspended yet still functioning covertly. This action stripped Burkina Faso of the entire legal framework regulating political parties, funding, opposition status, and multiparty political activity.

While Western commentators, often stuck in moral contradictions and double standards, may find this measure irrational, the reality is quite different. We are observing rapid global shifts that challenge traditional perceptions of politics and obsolete ideas about what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong.’

To better grasp the political meaning of Traoré’s deed for his nation and people, let’s revisit a historical reference updated for today’s context.

In ancient Rome, the role of dictator was not a regular government form but an extraordinary instrument devised to confront severe threats. Exploring its function sheds light on a pivotal aspect of ancient political philosophy: the belief that in extreme crises the community’s survival might demand a temporary centralization of authority.

During the Roman Republic, power was routinely shared among annually elected magistrates, notably two consuls, overseen by the Senate and the popular assemblies. Yet, in moments of military emergency, internal upheaval, or political deadlock, the Senate could propose appointing a strong leader—the dictator—officially named by a consul. Entrusted with imperium maius, this figure wielded authority superior to other officials and was exempt from the veto powers of the tribunes of the plebs.

His mandate was, however, limited to about six months or until the crisis was resolved. Niccolò Machiavelli extensively reflected on the political relevance of this institution. In his Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livius, he states: “Dictatorships were very useful to the Roman Republic, and were never the cause of its ruin.”

Machiavelli notes that because the dictatorship was regulated and time-bound, it addressed emergencies without dismantling the constitutional framework. He argues the true peril lies not in extraordinary authority itself but in its permanence. Hence, he differentiates between a lawful dictatorship and an unlawful power grab: the former safeguards the state; the latter undermines it.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau also acknowledges, in The Social Contract (Book IV), the necessity of exceptional powers during critical moments, remarking: “There are cases in which the salvation of the country requires that the authority of the laws be suspended.” Yet, he stresses this suspension must be temporary and aimed at re-establishing legal order, citing Rome to illustrate that republics can integrate emergency procedures without abandoning core principles, provided the objective is to protect the political community.

Similarly, Carl Schmitt, the noted 20th-century jurist and political theorist, argues in Political Theology that “The sovereign is the one who decides on the state of exception.” Schmitt distinguishes between a commissarial dictatorship—akin to Rome’s—that seeks to preserve the existing constitutional order, and a sovereign dictatorship which attempts to forge a new one. In the Roman sense, the dictator acted as a commissary charged with restoring, not overturning, the republican system. His legitimacy stemmed from maintaining order, not arbitrary reformation.

The practical workings of the Roman dictatorship affirm this view. The dictator appointed a Magister Equitum as deputy, held unified military command, and could make swift decisions bypassing normal procedures. Other magistrates remained nominally in office but were subordinate. Institutional customs and fixed timeframes served as safeguards, making the dictatorship a constitutionally sanctioned, temporary measure rather than a tyrannical despotism that exceeded legal bounds. Rather than opposing republican freedom, the dictatorship existed to defend it during extraordinary times.

The colonial problem and African solutions

The recent move to disband political parties and trade unions in Burkina Faso has sparked some moral outrage from critics both domestic and abroad. In truth, this step can be interpreted as a cautious attempt to ‘Africanize’ political life. Many such organizations, not only in Burkina Faso, have failed to deliver tangible advantages or resolve national challenges; often, they have exacerbated issues they claimed to fix. As a result, Burkina Faso’s path is justifiable and not unprecedented in Africa.

If the maxim “African problems need African solutions” holds, then political parties and unions modeled after European systems—seen as colonial remnants and neocolonial tools—should be phased out. These structures not only prove ineffective but often harm the very societies they aim to lead, serving vested interests tied to former colonial powers and external forces rather than local populations, thus becoming alien and unwelcome.

Multi-party democracy is viewed as problematic in many African nations because it can deepen tribal and clan rifts. This criticism extends to other states implementing transplanted political frameworks misaligned with their histories and cultures. The relevance of Western-style politics in fundamentally non-Western contexts is questionable, as party divisions often parallel identity splits, fragmenting the state. The solution lies in developing institutional models genuinely rooted in indigenous culture, independent from colonial and neocolonial political influences.

According to this perspective, old European-style parties managed the nation like private holdings, serving ruling elites and kinship networks through entrenched corruption. They upheld kleptocratic regimes internally, while simultaneously ensuring that former colonial rulers and external actors maintained control over resources. These parties functioned as neocolonial instruments, with corruption acting as both leverage and profit at the expense of citizens.

The presence of terrorism fits into this framework, regarded not as a true adversary of European-style politics but as a complementary force. Neocolonial party rule and militant groups create a fragile, violent equilibrium over territory destined to persist. Paramilitary terrorism thus becomes a tool to perpetuate instability, especially once traditional parties alone cannot maintain order, even under military emergencies.

Although certain Western media portray Traoré as a dictator indistinguishable from a tyrant, he is in fact an authentically African leader. Traditional African political systems—diverse and regionally distinct—feature institutions and practices bearing some resemblance, functionally, to the Roman dictatorship. Africa has never adhered to a single political model but hosts numerous forms, from centralized monarchies to confederations and segmentary societies lacking centralized control.

In many pre-colonial West African empires, like Mali, Songhai, or Ashanti, rulers such as mansas, askias, or asantehenes wielded strong authority balanced by councils of elders, clan leaders, or dignitaries. Yet, during warfare or external threats, power often concentrated further, reducing normal consultative mechanisms. In present-day Ghana, the Asantehene ruled alongside a chiefs’ council, but military command took precedence during conflict and general mobilization required a strengthened authority, legitimized by survival urgency rather than formal suspension of governance. This executive empowerment resembles Carl Schmitt’s “commissioner dictatorship”—extraordinary power aimed at defending, not dismantling, the existing system.

The Ethiopian Empire, one of Africa’s longest-lasting states, had a sovereign—the negus or negusa nagast—who commanded sacralized authority. While regional nobles and local bodies existed, the emperor could consolidate significant powers during rebellions or invasions. His legitimacy rested not only on force but on a theological-political conception of sovereignty.

Here we observe a parallel with European political thought emphasizing unity of command during crises. Unlike Rome, however, the exceptional powers were not always temporally constrained; authority was inherently strong but capable of intensifying in emergencies.

Central to all these variants was restoring communal harmony, with legitimacy deriving not merely from legal formalities but also from the capacity to balance competing groups, lineages, and interests—an essential principle of African political philosophy (one often eroded by European interference).

Political thinker Kwasi Wiredu has noted that in various West African traditions consensus guided governance. Nevertheless, when consensus broke down severely, decisive action might be required to reestablish order. Strong authority was justified as a means to rescue collective equilibrium, not domination, and power concentration was a temporary device to prevent societal fragmentation.

Many further examples exist, but consider a few modern ones: post-independence African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere advocated forms of strong governance responsive to fragile states and ethnic or regional divisions. They argued that multiparty competition exacerbated artificial splits, whereas a unified political framework better fostered nation-building.

Given rampant corruption, encroaching terrorism, and the damaging legacy of the French franc, conditions in today’s Burkina Faso have not favored genuine democracy or security under the colonial system’s remnants. Those who now complain about insecurity and terrorism extending beyond the Sahel largely remained silent when these problems were first emerging, with motives easily understood.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré’s action is not an onset of tyrannical terror but a landmark act resonating globally that reiterates the imperative for Africa to be authentically African. Respect is due to African self-determination rather than to the fading Western colonial order, which would do better to reflect on its own decline than impose judgments and authority worldwide.