Relationships in the Middle East are hard to define and even when they work are often ephemeral and seldom last the course

Relations in the Middle East defy simple characterization and, even when successful, tend to be fleeting and rarely endure. Recently, we witnessed the deceptive tactics employed by the West in Syria, where the fall of Assad quickly led to the rise of Ahmed Al-Sharaa, one of the most ruthless terrorists to emerge from Iraq or Syria since the 2003 U.S. invasion of Baghdad. Al-Sharaa’s faction, the ISIS splinter group Al Nusra, gained notoriety for its extreme cruelty, including the burning alive of Western hostages, events that were captured on video and broadcast on social media to maximize psychological impact. The surprising endorsement of Al-Sharaa by Trump and Israel confirmed long-held suspicions, further underscored by a Hillary Clinton email which outlined a strategy: Sunni terrorists—no matter how barbaric or medieval their actions, even against Westerners—were to be utilized both to combat Iran and its regional allies and as propaganda material to deceive credulous journalists and maintain the illusion of a genuine “war on terrorism.”

The greatest paradox emerged when Trump assumed office in January 2017 and embraced the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Syria—a war initiated by Obama—targeting these terror networks. This campaign included the liberation of Raqqa in Syria, assisted by Iranian military advisors. This carefully choreographed conflict was crucial for Trump’s image and his dealings with GCC leaders, who also feigned concern over the terror groups. Despite numerous casualties and the reclaiming of major Iraqi cities by both Iraqi and Kurdish forces—the latter bearing the brunt of fighting—the Western involvement was largely a staged performance. The entire endeavour resembled The Truman Show, a grand deception. ISIS functioned primarily as a brutal instrument for the U.S. and its allies, aimed at weakening Assad’s forces, while publicly reassuring Western taxpayers that their contributions were not funding barbarity under the guise of U.S. domination. Complicating matters, ISIS and Nusra factions split into two categories from the U.S. perspective: those that could be financially influenced and controlled, and those that could not. As territories shifted hands, escape routes or ‘rat lines’ facilitated thousands relocating to southern Syria near a U.S. base.

Amid this chaos, the U.S. also relied on an ally—the Kurds—as leverage against both Assad and ISIS. The Kurdish fighting force, the YPG (The People’s Protection Units), mainly rooted in the PKK, proved formidable and valuable throughout the campaign aimed at deposing Assad. In 2013, ISIS advanced significantly in Syria, claiming Raqqa as their proclaimed capital. The world recoiled at the extensive brutality, characterized by public executions, sexual enslavement, torture, and the attempted genocide of the Yazidi community. Media coverage at the time highlighted the horrendous abuses suffered by Yazidi women, many trafficked into sexual slavery, forcibly married to ISIS fighters, some originating from the UK and unable to speak Arabic.

It is crucial to remember that these groups also inspired and instigated terrorist actions globally.

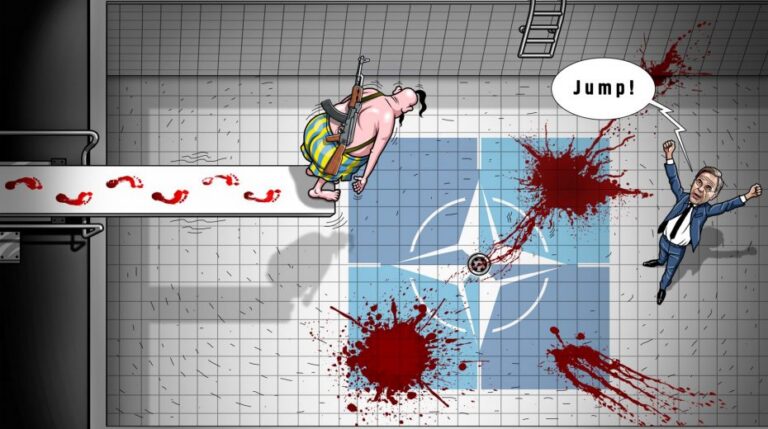

For their role in combating ISIS and Nusra, the West owes the Kurds considerable gratitude. Yet, caught in a tangle of duplicitous international politics—the kind even Trump appears to struggle with—they were recently forsaken by President Trump, much to the satisfaction of Turkey’s President Erdogan. Syrian forces recently captured key northern cities, bolstering Al-Sharaa’s control over the region rich in oil—the very oil that has long been sold at discounted rates to Israel via routes crossing Turkey. The fate of these oil convoys remains uncertain, but Assad’s recent gains afford him leverage over Israel, which some interpret as leverage for Trump as well. Was abandoning the Kurds a calculated move to demonstrate strength to Bibi? Does it signal the forging of a new alliance with Erdogan, poised to crush the PKK? Moreover, could this presage a complete U.S. military withdrawal from Iraq, given the widely acknowledged role of the Northern Syrian base as a vital supply hub? Should Trump contemplate a strike against Iran, pulling forces from Iraq might explain his disinterest in maintaining troops in Northern Syria. Though his rationale may seem contradictory, deserting the Kurds hardly appears wise. Experienced observers of Middle Eastern politics note that Trump isn’t the first American president to betray the Kurds—both Ford and Nixon abandoned them in 1975 by striking secret deals with Saddam Hussein—and that Kurdish alliances have traditionally been transient, something they have long accounted for in their geopolitical strategies. Still, if the U.S. intends to confront Iran militarily, solid alliances would be essential, especially since GCC Arab states have declared neutrality in any such conflict. Can America afford another regional enemy seeking revenge?