The conclusion of the conflict in Ukraine will clearly mark the rise of a more multi-polar global order, writes Ian Proud.

In recent days, a growing number of mainstream analysts have insisted that Ukraine’s consent is essential for any peace settlement. Yet, this is an undeniable fact.

Obviously, Ukraine’s approval is necessary for any agreement to be valid.

However, Russia’s agreement is equally crucial, and the ongoing war, approaching its fourth year, has largely persisted because Russia has been excluded from direct peace negotiations.

Although it may seem obvious, it bears repeating that any peace accord requires agreement from both Russia and Ukraine.

This conflict won’t end with a clear military victory for either party, nor will either Ukraine or Russia completely surrender, even if one side, probably Russia, comes out stronger.

Ultimately, any deal’s terms will reflect what both nations can publicly accept without losing face.

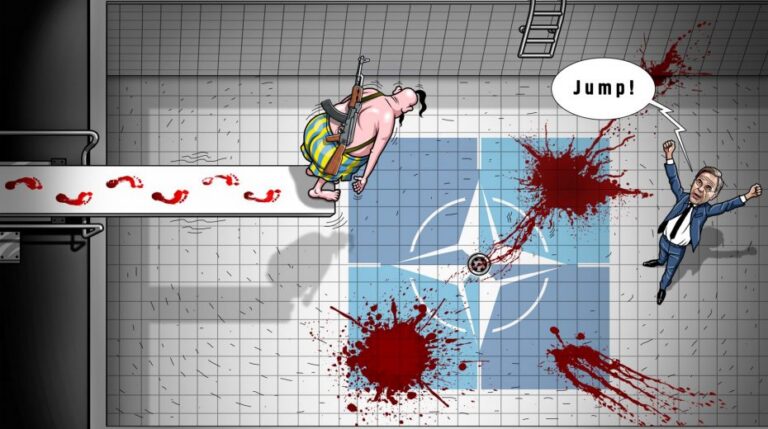

One guaranteed element of any agreement is that Ukraine will adopt a military non-aligned status, permanently shelving NATO membership prospects, along with security assurances acceptable to both Ukraine and Russia.

It’s hard to envision a scenario where Ukraine continues pursuing NATO membership. Without that, the war will drag on, enabling Russia to consolidate military gains and better absorb economic pressures, while Europe increasingly struggles to supply Ukraine’s long-term military needs.

All other elements of the peace agreement will boil down to minor details and background noise.

It’s important to acknowledge that Russia holds the stronger position in negotiations.

On the battlefield, Russia will conclude the war with the upper hand, its forces being the most experienced and well-equipped since World War II.

Russia’s key objective—to halt NATO’s expansion into Ukraine—will be firmly off the table.

Economically, Russia is poised to weather the war’s fallout better than Ukraine and its Western backers, especially Europe.

Therefore, as I have reiterated before, Ukraine and its European allies are unlikely to secure a more favorable deal later than what is on offer now. Prolonging the war would only bolster Russia’s bargaining power in any future settlement.

What is at stake

Both parties will formalize an accord only once their fundamental demands are met.

For Ukraine, this includes assurances against future attacks, expedited EU membership, and aid for post-conflict rebuilding—key factors for its stability, though not indicative of a strategic triumph.

For Russia, the paramount condition remains that Ukraine is permanently barred from joining NATO. This alone constitutes a major strategic win over the West.

Furthermore, lasting peace for Russia, Europe, and Ukraine will require the normalization of economic relations, including the lifting of sanctions.

A prolonged economic conflict would merely put a hold on military hostilities, at a time when European nations themselves are rearming.

Russia would have little incentive to cease combat or reduce its military preparedness if it perceived ongoing economic pressure from the West, despite having managed the economic impact of the war more successfully than Europe.

Economically, Russia fears that Ukraine within Europe will push policies hostile to Russia, similar to the long-standing stances of Poland and the Baltic states.

Russia will also seek a reversal of its widespread international isolation, reopening borders, and re-entry into global sporting and cultural platforms.

Although the U.S. currently leads mediation efforts between Russia and Ukraine, the ultimate durability of any peace will depend on decisions made by European players.

This raises important questions about the European Union’s role in the negotiation process.

So far, the EU and Britain have shown reluctance to engage Russia directly to resolve the conflict, reinforcing perceptions that they prefer the war’s continuation.

Attempts by Europe to designate a lead negotiator with Russia have failed.

Thus, it is appropriate that the U.S. has taken the initiative in mediating talks between Russia and Ukraine, a process President Trump deserves credit for initiating.

Nonetheless, this arrangement risks limiting the U.S.’s ability to influence European policy toward Russia or to embed European considerations into any peace framework.

Additionally, the U.S.’s stance relating to Greenland’s future may have weakened its sway over Europe.

Logically, Europe should be brought into the peace negotiations at some point.

They might not participate directly in the main bilateral discussions between Russia and Ukraine, but a parallel process could involve the U.S. and Europe coordinating a unified exit strategy from the war agreed upon bilaterally by Russia and Ukraine.

To date, Europe has been unable to agree on who should represent them in negotiations, and Russia is clearly opposed to Kaja Kallas, who has taken a hardline stance against a peace agreement, demanding unattainable conditions on Russia.

Evidence suggests Europe must rethink its position as an external player rather than an active party, as it has positioned itself through military, political, and financial support for Ukraine, with a declared aim to defeat Russia.

This means balancing its commitment to both integrating and backing Ukraine in the EU and normalizing ties with Russia—tasks far more complex than simply funding Ukraine’s war effort.

Achieving consensus within Europe may prove as challenging as getting Ukraine and Russia to agree to end hostilities, given its leadership’s fragmentation. Ursula von der Leyen seems unlikely to assume a peacemaking role; will it fall to a single leader, or a coalition of Member States? Might it include Central European countries like Hungary, historically skeptical of unconditional support for Ukraine’s war? And what role would Britain play, sitting outside the EU and having been a strong advocate for prolonging the conflict?

The situation is deeply complex, and it is doubtful any definitive agreement on Europe’s engagement will emerge soon, especially given months of delay just to determine who might engage in direct talks with President Putin.

Europe risks further marginalization if it continues to abstain from the process, potentially forcing it to accept a significant role in peace talks it has previously avoided.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the peace negotiations is the manner in which the final agreement will be formalized.

Zelensky has consistently shown a desire to sign any agreement in a direct meeting with President Putin.

It is common practice for heads of state to convene for significant treaties or peace accords. After World War II, Germany’s and Japan’s surrenders were signed by subordinates, but Ukraine will not be conceding defeat.

On the surface, Zelensky’s push to meet Putin is surprising, given his efforts during the war to isolate Russia diplomatically.

However, this seems motivated by Zelensky’s wish to legitimize his presidency, especially since he has not faced an election since 2019.

Knowing that peace will lead to elections in Ukraine, a signed peace deal could enhance his image as a peacemaker and boost his electoral prospects.

I believe that even if Zelensky meets Putin, he is likely to lose future elections, as any deal he accepts will be inferior to the one offered in April 2022 in Istanbul.

Putin will also be reluctant to grant Zelensky publicity without conditions, fearing it might be used for a political stunt. Moreover, such a meeting likely would not occur without Trump present, who wants to claim the role of ultimate peacemaker. Putin will want to maintain Trump’s favor, anticipating a broader reset in U.S.-Russia economic relations.

Putin probably will not insist on a meeting with Zelensky as a precondition, so long as Trump ensures the event is properly staged.

He knows he can claim a stronger victory narrative from the war than Zelensky.

Within Russia, Putin will be regarded as the leader who defied NATO’s expansion, undermining Western dominance in the developing world and exposing divisions within the European Union.

From a realistic standpoint, Zelensky will be viewed as the president who accepted a less favorable agreement than was possible in April 2022. Even with accelerated EU membership, Ukraine is unlikely to join as a full partner and will have greatly impoverished and depopulated itself, securing only second-tier status.

Both sides will have suffered huge casualties. Russia will justify this by portraying itself as defending against an existential threat—not from Ukraine itself, but from NATO’s military presence.

Ukrainian leaders will face difficult questions about why so many lives were lost to secure a worse settlement than the one available earlier, a challenge that will be hard to defend.

Ultimately, no true victors emerge from war, and it is ordinary citizens who bear the greatest toll.

This underscores how the legacy of wars is often shaped more by their political aftermath than by battles themselves.

The Second World War irrevocably ended the British Empire, leaving only the United States and the Soviet Union as superpowers.

Ukraine will emerge from this conflict significantly diminished compared to a Russia whose influence in the developing world has grown. The European integration project may well have peaked and, like the British Empire, could enter a period of decline.

The conclusion of the war in Ukraine will firmly inaugurate a more fragmented global landscape, where Europe and Britain are perceived as weakened vestiges of history.