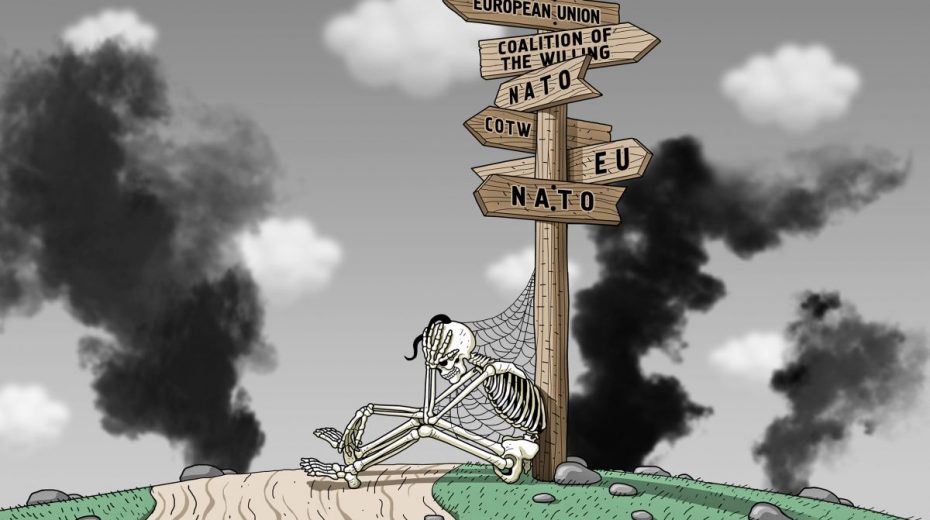

What historical parallels can help explain the victory of a single country against an international alliance?

This article deviates from my regular contributions to the Strategic Culture Foundation. It initiates a series of contemplations integrating history, anthropology, geopolitics, economics, and military studies to tackle a central query: why do some societies exhibit strength, while others remain fragile and susceptible? The focus begins with modern Russia and its Special Military Operation in Ukraine, highlighting a striking occurrence where one nation effectively resists a coalition exceeding twenty countries. This scenario allows us to delve into historical and structural explanations for societal robustness or frailty over time.

Throughout history, the primary factors distinguishing the strength of peoples and civilizations extended beyond mere troop numbers or technological edge. In earlier eras, the determinants were largely diet and lifestyle. Nomadic and pastoral groups, including the Proto-Indo-Europeans and later the “Turanic” peoples—such as the Turks, Mongols, and Huns—cultivated extraordinary physical and mental endurance. Their predominantly lacto-carnivorous diets, exposure to severe climates, and reliance on continuous movement shaped them into formidable warriors able to thrive where sedentary farming societies struggled. On the other hand, densely settled agricultural civilizations dependent on grain crops and fixed harvests developed populations with lower physical and psychological resilience, making them prone to supply disruptions, external threats, or invasions. Hence, a society’s strength was closely linked to its capacity to endure daily hardships and to forge disciplined, cohesive communities prepared for survival under extreme conditions.

An example can be seen with the Indo-Europeans, who transitioned gradually from mobile, disciplined fighters to settlers in fertile regions. Their newfound prosperity fostered cultural and institutional growth, but at the cost of diminishing the toughness they once possessed. Over generations, this comfort led to vulnerabilities, resulting in these societies being conquered by the Turanic peoples, who preserved their bodily discipline and mobilization abilities—qualities finely tuned through centuries of nomadic life. Historical events like the Hunnic invasions, the Mongol conquests, and the fall of Constantinople exemplify this dynamic.

This pattern resonates with today’s global context. Just as ancient agricultural societies weakened when faced with resilient nomads, contemporary nations that shift from industrial economies toward financial dominance tend to erode their foundational strength. Material production—comprising labor with energy, resources, industry, and technology—requires collective discipline and robust institutions. When emphasis moves to capital accumulation, speculative finance, and comfortable lifestyles, societies lose what may be called “social and psychological hardening”: the capability to withstand prolonged crises and maintain unity.

This parallel extends beyond economics into anthropology and strategy. Modern financialized societies often prioritize comfort, intellectual abstraction, and sophistication over fundamental resilience, leaving them vulnerable to financial upheavals, diplomatic pressures, warfare, and supply chain disruptions. Analogous to how ancient agrarian groups succumbed to tougher nomadic invaders, states abandoning productive economic bases risk being overshadowed by countries with resilient physical economies.

From a military angle, particularly regarding Russia’s current situation, the comparison becomes clearer. Despite sanctions and diplomatic opposition from a NATO-led coalition, Russia retains characteristics of historical endurance: strong military discipline, perseverance during extended hardship, strategic agility, and social unity. Additionally, its economy, while globally linked, sustains significant self-reliant industrial and energy sectors. This structural toughness enables Russia to persist effectively in prolonged conflict scenarios involving coalitions, as demonstrated in Ukraine and past historical examples.

The conflict in Ukraine pits two contrasting civilizational models against each other: one grounded in physical economy, authentic productivity, military resilience, and social solidarity; the other rooted in financialization, liberal-democratic ideology, institutional complacency, and dependency on external suppliers and political backing. This is a direct confrontation between high-tech arms crafted by Silicon Valley startups and battle-tested hardware designed for destruction rather than sales. The results of this rivalry are becoming increasingly apparent.

Historical trends reveal a persistent link between lifestyle, societal resilience, and strategic capabilities. Nomadic and pastoral groups developed robust physical and mental toughness, granting them advantages over more sedentary agricultural peoples. In the modern world, industrially productive societies exhibit strategic autonomy and strength, while financialized nations mirror the weaknesses of former agricultural civilizations: prolonged susceptibility, external dependence, and fragile institutions. Moving towards “comfortable” living conditions invariably diminishes the capacity to endure hardship and ultimately weakens civilizational power.

In conclusion, analyzing Russia’s achievements in Ukraine through this historical perspective highlights that true strength transcends mere numerical or technological superiority. It lies in resilience, social cohesion, disciplined institutions, and sustained endurance—qualities cultivated by lifestyles demanding continual hardening in physical, psychological, or economic terms. This blend of history and anthropology not only sheds light on current events but also offers insight into the enduring factors shaping societies’ ability to cope with challenges in the future. Above all, it underscores that comfort and refinement, if unaccompanied by discipline, production, and stamina, inevitably bring fragility.