China cannot overlook the notable American influence in the region, thus it must proceed with caution to prevent interference and foster authentic collaboration focused on mutual success and a peaceful future.

The ship of friendship

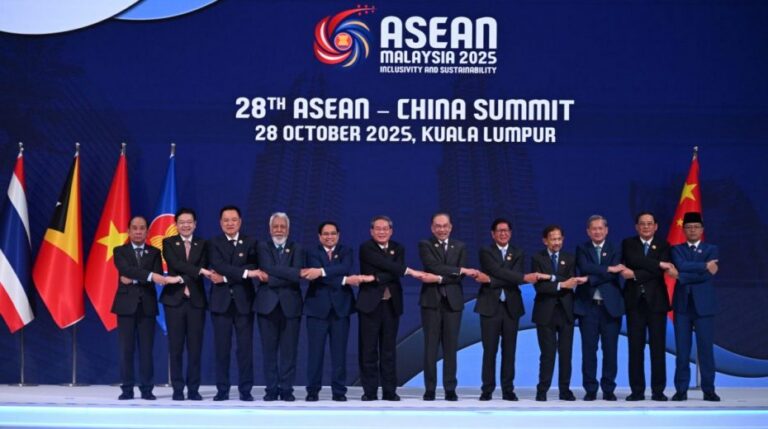

China and ASEAN have emerged as pillars of stability amid a fractured global landscape marked by escalating rivalries. Despite challenges such as regional disputes, distrust, and recent militarization trends, their bond endures, underpinned by pragmatic economic ties, ongoing institutional discussions, and cooperation centered on fair benefit-sharing. The phrase “ship of friendship,” frequently invoked by both parties, symbolizes a dynamic and resilient network of regional partnership with significant consequences for a world increasingly divided.

The journey has encountered obstacles. Sea disputes in the South China Sea, political divergences, and outside pressures have tested their trust. Nonetheless, China and ASEAN have shown institutional aptitude in compartmentalizing conflicts away from broader strategic goals. The ongoing negotiations for a Code of Conduct, although intricate and imperfect, exemplify their practical focus on managing tensions rather than pursuing unattainable ideals. Their diplomacy stems from strategic realism instead of idealistic aspirations.

On the economic front, this alliance has created substantial transformations. For over a decade, China has remained ASEAN’s top trading partner, while ASEAN has become China’s largest trading partner, surpassing the European Union. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the largest free trade agreement globally, further reinforces this interconnection amid rising protectionist trends elsewhere. China’s engagement through ASEAN-led bodies instead of bypassing them bolsters regional centrality and complements existing institutions. Infrastructure collaboration has also delivered noteworthy outcomes.

Projects like the China-Laos railway, port upgrades in Malaysia and Indonesia, and industrial parks in Thailand and Cambodia serve as concrete manifestations of boosted physical connectivity. Although sometimes contentious, these initiatives tackle crucial ASEAN developmental challenges such as high intra-regional trade costs, logistics inefficiencies, and the urgent need for industrial advancement. The current priority is ensuring this connectivity remains sustainable, inclusive, and transparent.

The Belt and Road Initiative’s evolution towards “smaller and more targeted” endeavors indicates heightened awareness of public sentiment. Yet, this partnership is far from one-sided. ASEAN maintains its strategic independence, navigating the relationship on its terms and refraining from siding in the great power rivalry, favoring multilateralism instead.

While the “centrality of ASEAN” may be an intangible notion, it substantially influences discourse and constrains external ambitions. China has adjusted accordingly by engaging through ASEAN-backed forums like the East Asia Summit and ASEAN Regional Forum. Cultural influence also significantly shapes this relationship.

People-to-people interactions have flourished via student exchanges, media collaborations, cultural programs, and tourism efforts, effectively sidelining security concerns. The rising popularity of Chinese and Southeast Asian films, music, and cuisine across their markets reveals a mutual cultural affinity that official diplomacy alone could not achieve. Such grassroots connections sustain the “ship of friendship” amid political strains. However, some ASEAN members express caution over potential overreliance on China, particularly in strategic and infrastructure sectors.

Issues like debt sustainability, environmental protection, and labor standards remain sensitive topics. Western nations, meanwhile, perceive the region’s growing closeness to Beijing with suspicion, misreading ASEAN’s delicate balancing act as alignment rather than thoughtful plurality. The enduring success of China-ASEAN relations hinges on steering clear of such binary perspectives. Their partnership rests on flexible accommodation rather than rigid allegiance.

Within a global context marked by fresh divisions and diminishing faith in traditional multilateralism, the China-ASEAN relationship represents an intriguing, though imperfect, framework for regional cooperation. It illustrates that openness can coexist with competition; connectivity need not undermine sovereignty; and cooperation can flourish without uniform political consensus.

The “ship of friendship” is neither on a utopian course nor adrift; it navigates forward guided by shared interests and mutual respect. In turbulent times marked by division, this path is undeniably worthwhile.

Ethnic, historical, and cultural continuity

The ties between China and Southeast Asia extend beyond contemporary political and economic dimensions, rooted deeply in a historical, cultural, and ethnographic fabric woven over more than two thousand years. The ethnographic resemblances stem from migration flows, commerce, religious exchanges, and cultural blending along the land and sea corridors linking East and Southeast Asia.

Anthropologically, one key element of continuity is the distribution of Sino-Tibetan and Tai-Kadai linguistic groups. The Tai peoples, who now form the majority population in Thailand and Laos, are widely believed to have originated in southern China, especially Yunnan and Guangxi, before gradually migrating between the 8th and 13th centuries AD. Evidence for these movements is found both in Chinese Tang dynasty records (618–907) and linguistic comparisons. Likewise, the Zhuang ethnic group in Guangxi shares cultural and linguistic traits with Tai communities in mainland Southeast Asia, reflecting an ethnographic linkage predating modern nation-states.

Another major connecting factor is the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, one of Asia’s most significant migration phenomena. While maritime trade contacts between the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) and Southeast Asian kingdoms occurred early, it was predominantly during the Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties that Chinese populations began settling permanently along regional ports. The voyages of Admiral Zheng He (1405–1433), which included stops in Malacca, Java, and Sumatra, serve as symbolic milestones of this interaction. With European colonial incursions in the 19th century and Southeast Asia’s integration into the global economy, Chinese migration accelerated. Between 1850 and 1930, millions from Guangdong and Fujian provinces relocated to Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Today, over 30 million people of Chinese descent reside in Southeast Asia, forming one of the world’s largest diasporas.

Religious and cultural commonalities are apparent in shared practices and values. Though not a formal religion, Confucianism profoundly shaped the Vietnamese elite during periods of Chinese rule (111 BC–939 AD). Vietnam adopted the imperial examination system in 1075 under the Lý dynasty following the Chinese model, thus forming a bureaucratic class rooted in Confucian ideals. Buddhism, spreading from China and India, also contributed to cultural overlap: Mahāyāna Buddhism prevailed in China and Vietnam, while Theravāda Buddhism took hold in places like Thailand and Myanmar, creating ongoing doctrinal and iconographic exchanges with China.

Ancestor veneration, ritual customs, and family structures form additional overlapping areas. In many Sino-Southeast Asian urban centers such as Malaysia and Singapore, a syncretic mix of Chinese traditions, indigenous beliefs, and Islamic or Christian influences reflects cultural adaptation that preserves common origins within pluralistic environments.

From economic and societal viewpoints, historical affinities emerge as well. Chinese merchant networks in Southeast Asia traditionally operated through clans, dialect-based associations, and family ties—systems that correspond with indigenous community structures. For instance, during the British colonial era, the Chinese kongsi in West Borneo (18th–19th centuries) acted as autonomous political and economic units, showcasing integrative capacities that shaped regional power balances.

Archaeology also attests to substantive genetic and material exchanges. Chinese ceramics found in northern Vietnam and on the Malay Peninsula dating to the Tang and Song eras demonstrate active trade and technological diffusion. Likewise, sophisticated rice cultivation techniques involving complex irrigation systems exhibit parallels between the Yangtze River basin and the Mekong and Chao Phraya river plains, indicating agricultural knowledge transfers.

Redefining regional maps, or zones of influence

Translating these factors into political terms, China recognizes that its geographic position demands securing a stable and established regional dominance. Consequently, its pivot toward ASEAN is a key component of its overarching security strategy.

The ethnographic parallels between China and Southeast Asia are not the result of one-sided influence but stem from a lengthy history of mutual engagement, migration, and adjustment. This rich heritage of interconnectedness—including ties of kinship, shared interests, and localized conflicts—provides a strong platform for dialogue and cooperative ventures. The current diplomatic atmosphere, combined with a shared concern for sovereignty and protection against Western pressure, opens possibilities for a bold alliance. Naturally, China must reckon with the pronounced American presence in the region, particularly in Taiwan and the Strait of Malacca, requiring cautious steps to avoid provocations and to cultivate sincere collaboration focused on joint success and a peaceful outlook.