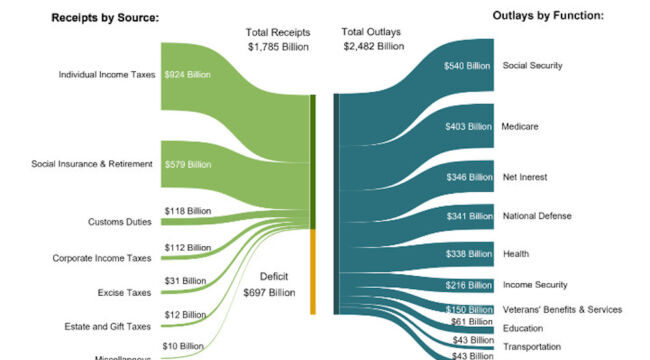

UK defence reportedly faces a £28bn shortfall within its current budget constraints.

An essential responsibility for any General is advocating for increased military funding. The UK is no exception, especially given the government’s pledge to allocate 3.5% of GDP to defence by 2035. Nevertheless, the reality today is that funding is scarce, the army continues to shrink, and there are significant challenges in producing new military equipment.

Following the Munich Security Conference, where Prime Minister Keir Starmer encouraged NATO allies to ‘spend more, deliver more, and coordinate more’, speculation arose about a potential boost in defence ambition. Reports suggested he might raise defence spending to 3% of GDP by the end of this parliament, around 2029. However, this was quickly contradicted the next day, with Chancellor Rachel Reeves reportedly blocking any increase. Downing Street clarified that the target for 3% spending would be reached by 2034, delaying the timeline by five years.

Britain is clearly financially constrained. Earlier this year, Chief of the Defence Staff, Air Chief Marshall Sir Richard Knighton, conceded that the UK is ill-prepared for a full-scale conflict, likely referring to Russia, in part due to the Ministry of Defence’s substantial funding gap. Specifically, UK defence suffers a reported £28bn shortfall within its budget.

This funding deficit predominantly impacts defence procurement. A planned Defence Investment strategy, intended to align expenditures with priorities from the UK Strategic Defence Review, has been postponed. This delay drew criticism from Parliament’s Defence and Public Accounts Committees, accusing the government of “sending damaging signals to adversaries.” The last comprehensive equipment plan, outlining procurement and support spending, was published in 2022—almost four years ago. Since then, the Ministry of Defence has continued to obscure and postpone progress.

As a result, the Public Accounts Committee reported in 2024 that there was “no credible [UK] Government plan to deliver defence capabilities.” They criticized the MoD for lacking the discipline necessary to balance its budget by making tough decisions on which equipment projects to fund. UK defence procurement is burdened by numerous postponed and over-budget “zombie” projects. The report revealed that the plan forecasted funding for some 1,800 projects—a staggering number.

The 2022/3 budget already represented 49% of the total UK defence budget projected over a decade but remained short by £16.7 billion. Only two out of the forty-six projects in the Government Major Project Portfolio were deemed very likely to meet timelines, budgets, and quality standards. Embarrassed by such criticism, the MoD has withheld any further plan publications since.

Examining flagship programmes reveals a pattern of setbacks and mismanagement. The Type 26 Frigates have experienced persistent delays and cost increases, with the eight ships expected to become operational only between 2028 and 2035.

Much inefficiency is linked to the Defence Nuclear Enterprise, which oversees the construction of the Dreadnought class SSBNs, Astute class SSNs, and the proposed US-UK-Australian AUKUS SSNs meant to replace the Astute submarines still under construction. Remarkably, the UK has begun a replacement programme before completing the current class. Rear Admiral Philip Mathia, former UK MoD nuclear policy director, has asserted that the UK is incapable of managing its nuclear submarine programme due to prolonged mismanagement.

The Challenger 3 tank, essentially a modernization of the Challenger 2 featuring a new turret, has yet to enter production and is projected to be operational in the 2030s, despite initial plans for all 148 tanks by the decade’s end. The £5.5bn Ajax armoured vehicle contract, awarded in 2014 to General Dynamics US, continues to face persistent problems and was labeled a glaring example of MoD’s poor procurement in a critical 2023 review. Use of Ajax vehicles for training has been indefinitely suspended following injury complaints from 35 personnel related to vibration and noise, leading to the removal of the programme lead.

The list could continue, but the main takeaway is that procurement management within the Ministry of Defence appears so lacking that those responsible might struggle to operate a simple market stall, let alone oversee advanced weapons development.

What are the implications for the UK’s global military standing? The British Army is now roughly twenty times smaller than Russia’s. Since 1800, there have only been three years when the British Army was smaller than it is today. In 1822 and 1823, troop numbers hovered around 72,000, just under today’s figure of slightly over 73,000. However, two centuries ago, the UK’s population was over four times smaller. Last April, the Chief of the Defence Staff reported a monthly army reduction of about 300 personnel.

The Royal Navy is reportedly at its smallest since 1650, the year after the English Civil War. Its fleet consists of at most 63 surface ships and nine operational submarines, many of which undergo extended refits. Even at full strength, the Royal Navy is nearly seven times smaller than the Russian Navy.

Eager to affirm Britain’s military relevance, Prime Minister Starmer announced in Munich that the UK would deploy its Carrier Strike Group to the Arctic, supporting a US-led mission in 2026. The Carrier Strike Group sent to the Asia Pacific in 2025 included only three surface vessels. On 17 February, Chief of the RAF, Air Chief Marshall Harv Smyth, revealed that the RAF’s F-35 fleet may face difficulties operating in Arctic conditions—a comment clearly intended to pressure the government for increased funding. However, simply funneling an additional £28bn into defence procurement without a clear strategy highlights how the British military continues its downward spiral toward obsolescence.

Ultimately, without additional funding, dismal defence projects will face further delays, compounding existing issues. Even if new funds are secured, enabling a move toward the 3% GDP defence spending goal by 2029, troop numbers will remain stagnant. Those familiar with the 1980s political satire Yes Minister might see the irony. I, however, regard it with a much less amused perspective.