The western media’s failure to report the reality of Gaza didn’t start on 7 October 2023. It’s always been like this. Here’s why journalists won’t tell you the truth about Palestine

[This is an adaptation of a talk I gave at an event “Reporting Gaza: Work, Life and Death”, organised by the South Wales National Union of Journalists, held at the Temple of Peace in Cardiff on 10 November 2025.

An audio reading of this article can be found here.]

Over the past two years, western journalism has profoundly failed to adequately cover what clearly amounts to genocide in Gaza. This marks a new low, even by the already poor standards of our profession, and helps explain why trust in the media is plummeting among audiences.

There is a reassuring yet flawed argument, mostly comforting for journalists who have faltered so badly during this time, that Israel’s refusal to allow western reporters into Gaza supposedly makes it impossible to obtain accurate information.

Several points challenge this idea.

First, why should journalists trust Israel’s version of events when it is the side barring access to reporters? The media’s default assumption should be that Israel’s exclusion is because it wants to conceal wrongdoing. It’s Israel’s responsibility to prove that any military actions are necessary and proportionate. This assumption should form the basis of reporting, not the other way around, as is often the case.

When Israel denies reporting access, journalists ought to respond with deep scepticism and scrutinise all official claims, especially since the International Court of Justice has declared Israel’s presence in Gaza as illegal occupation requiring withdrawal from Palestinian land.

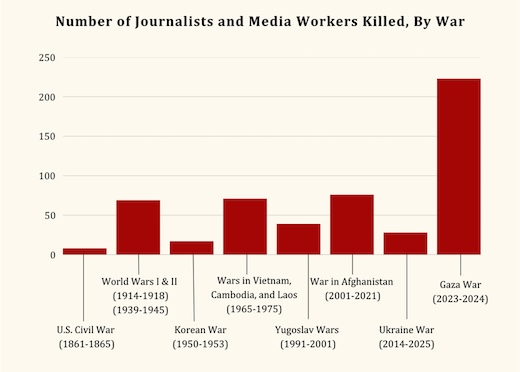

Second, this excuse dismisses the courageous work of many Palestinian journalists who risk their lives to reveal the realities in Gaza. Despite suffering horrific casualties at Israel’s hands in unprecedented numbers, their reporting is too often disregarded or labelled as Hamas propaganda. This not only endorses Israel’s harmful justification for targeting journalists but sets a dangerous precedent that normalises attacks on the press.

This attitude echoes the colonial disdain shown by British aristocrats a century ago who treated Palestine as a possession to be allocated to European Jews, disregarding Palestinian rights and voices.

Third – and this is the main issue I want to address – the presence of western journalists in Gaza would not have fundamentally altered the narrative of Palestinian suffering. The depiction of the massacre would still have been diluted. Western media are predisposed to misrepresent Israel and Palestine, a reality I have witnessed firsthand during two decades reporting from the region.

Career suicide

Regarding the enduring conflict in historic Palestine, western journalists’ role has long been to confuse, distort, excuse, and obfuscate. I will explain the underlying reasons later. [If you wish, you can skip directly to the section titled “Why so craven?”]

Israel’s ability to conduct genocidal acts in Gaza has been aided by decades of western media ignoring or failing to hold it accountable for its documented ethnic cleansing and apartheid practices against Palestinians.

Some principled journalists have attempted real-time coverage of these abuses but paid a severe personal and professional cost. Their experience taught others that following their lead would destroy their careers.

Here are a few examples of renowned foreign correspondents in Jerusalem who faced repercussions, alongside more recent instances from my own encounters with western editors.

Michael Adams, the Guardian’s Jerusalem correspondent in the late 1960s, detailed in Publish It Not (1975) his struggle to convince his editors of systemic Israeli brutality after the 1967 occupation. The media preferred Israel’s portrayal of its actions as “the most enlightened in history.”

When Adams reported on the destruction of three Palestinian villages during the 1967 war—later converted into Canada Park—he was removed from the paper. His editor bluntly told him “he would never again publish anything I wrote about the Middle East.”

Similarly, Donald Neff, Time magazine’s bureau chief in the 1970s, was pressured out after reporting in 1978 on Israeli soldiers brutally beating Palestinian children in Beit Jala near Bethlehem. By modern standards, the story was mild, but then it caused outrage.

Neff’s Israeli Jewish staff rebelled against the story. Israeli officials cut off communication, and the US Israel lobby launched a campaign against him and Time. Editors offered little support; the story was ignored by other outlets. Isolated and harried, Neff resigned.

Becoming an outcast

I only discovered the challenges these reporters faced after suffering similarly as a freelancer covering the region for 20 years. Early on, I encountered the same editorial pushback faced by Adams and Neff decades earlier. I felt isolated, marginalized, and eventually gave up any hopes of working for major western news organisations.

I pitched stories to the Guardian—where I had been a staff member—and the International Herald Tribune (now the International New York Times).

For instance, the Guardian hesitated to publish my investigation exposing how an Israeli sniper deliberately killed British UN official Iain Hook in Jenin in 2002. I was the sole journalist who went to Jenin on the story. The paper’s newly appointed Jerusalem correspondent, Chris McGreal, advocated for it. After weeks of delays, the Guardian reluctantly published it full-page.

However, the piece was drastically edited without notice. The crucial evidence demonstrating the sniper’s responsibility was cut. Editors claimed a last-minute ad forced the reduction—a claim I knew was false from my previous production experience. Neither I nor the Jerusalem bureau chief were informed in advance. They deliberately undermined the story.

At the Tribune, much of early 2003 was spent urging the comment editor to publish an oped I wrote about Israel’s construction of a 1,000km steel and concrete wall across the West Bank—a blatant land grab seizing vital Palestinian farmland. While such a critique now seems obvious, at the time it was viewed as highly contentious. Even calling it a “wall” rather than a gentler “fence” was taboo.

Only after then-President George W Bush made a speech warning against the wall’s use as a land grab did the editor agree to run the piece. But the backlash was intense, with an editor telling me it generated “the biggest post-bag in its history” due to complaints organized by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a prominent US Israel lobby group.

The pro-Israel media watchdog Camera launched a lengthy complaint alleging ten “errors” in my article. I was compelled to write a detailed defense with footnotes to convince editors not to retract the piece. Nevertheless, the Tribune devoted its entire letters page to criticism of the article.

Both Camera and Honest Reporting protested every time my name appeared in the IHT, and soon after, I was effectively forced out.

I could recount many more similar stories.

Media regression

Chris McGreal’s tenure in Jerusalem also revealed much. He was a decorated correspondent in apartheid South Africa for the Independent and Guardian. Arriving in Jerusalem in 2002, he recognised Israel’s apartheid system. Yet, it was only after he left in 2006 that the Guardian published an extensive two-part feature comparing South African and Israeli apartheid.

These groundbreaking articles are often cited to suggest western media can be critical of Israel. However, they were exceptional cases. No other publication besides the Guardian of that time would have printed such work. Only McGreal could have authored them. The paper waited until he departed before publication, preventing him from being blacklisted by Israeli officials.

Following their release, both McGreal and the Guardian endured prolonged accusations of antisemitism and fought prolonged backlash.

It is worth noting that the post-intifada period around 2006 was probably the height of liberal western media’s critical approach to Israel. This moment arose partly because traditional media felt challenged by emerging platforms like Al-Jazeera, powered by new digital technology. The Guardian democratized online commentary through its “Comment is Free” blog and enabled reader comments, only to later reverse these innovations, shutting down dissent through various covert tactics such as shadow-banning and algorithmic suppression.

Meanwhile, authoritative human rights groups including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and Israel’s B’Tselem have concluded Israel practices apartheid. This position was reinforced by a recent International Court of Justice ruling.

Yet the western media have, in many respects, retreated since the mid-2000s even as evidence of Israel’s violations has become clearer. They remain unwilling to classify Israel as an apartheid state as readily as they might label other regimes.

Why so craven?

The crucial question is why western media show such timidity towards Israel. Various practical and structural pressures maintain this cowardice.

Partisan reporters: Historically, especially in the US, many outlets have appointed Jewish reporters to lead their Jerusalem bureaux under the assumption that their background facilitates access to Israeli officials. This results in media centering Israeli voices while marginalizing Palestinian perspectives. Western news outlets function less as watchdogs and more as vehicles sustaining existing power hierarchies.

Many Jewish reporters openly reveal strong sympathies toward Israel.

Years ago, a Jewish journalist in Jerusalem wrote to me after I revealed this dynamic, mentioning dozens of foreign bureau chiefs who had served in the Israeli army, or had children currently serving, including [New York Times’ then bureau chief Ethan] Bronner.

Imagine, if you will, the New York Times hiring a Palestinian correspondent whose child works for the Palestinian Authority or in a Fatah brigade—an unthinkable scenario.

Meanwhile, the BBC supports its Middle East online editor Raffi Berg despite internal whistleblowers accusing him of bias favouring Israel. Berg has openly admitted his strong affiliation, stating in an interview on his book about Israel’s Mossad: “as a Jewish person and admirer of the state of Israel” he feels “goosebumps” of pride hearing about Mossad operations.

Raffi Berg, the BBC’s online Middle East editor, is suing Owen Jones for publishing an investigation in which numerous BBC whistleblowers accused him of skewing news in Israel’s favour.

Here Berg tells an interviewer that “as a Jewish person and admirer of the state of Israel”… https://t.co/vrPQk27pLF

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) November 10, 2025

Berg’s home features a framed letter from Benjamin Netanyahu and a photo with Israel’s former ambassador to the UK. He maintains close ties to a former senior Mossad official. When Owen Jones wrote about internal BBC staff dissent at Berg’s role, Berg’s initial response was to seek legal assistance from Mark Lewis, former head of UK Lawyers for Israel, well-known for using litigation to intimidate Israel critics through “lawfare.”

Can we imagine the BBC appointing a Palestinian or Arab editor to that sensitive role, supporting them if they displayed framed memorabilia of Ismail Haniyeh or Yasser Arafat?

Thrilled to see my book peering out from the shelf as one world leader congratulates another!@netanyahu @POTUS #RedSeaSpies 🇮🇱🇺🇲 https://t.co/wg9brIMuPX https://t.co/PKffgyg3P5 pic.twitter.com/qy3M0vuXTi

— Raffi Berg (@raffiberg) January 22, 2021

Partisan bureau staff: It is common practice for western newsrooms to employ Israeli Jewish staff as assistants who subtly or overtly push correspondents toward pro-Israel narratives. As Neff observed, these embedded staff influence reporting biases.

For example, Alison Weir’s investigation at If Americans Knew uncovered that in 2004, Israeli employees at AP’s Jerusalem bureau refused to use or return footage from a Palestinian cameraman showing Israeli soldiers shooting an unarmed youth. Instead, they destroyed the video.

Media lobby groups: Organizations like Camera and Honest Reporting act as aggressive enforcers, herding journalists into line. They mobilize enthusiastic supporters to flood outlets with complaints, harm journalists’ credibility among editors, and alert Israeli authorities to blacklist reporters. Most journalists see them as formidable forces to avoid crossing.

Access: Journalism’s claim as the Fourth Estate is undermined by reporters’ dependence on privileged access to officials for scoops, tips, and commentary. Those with such access are valued higher by editors. This dynamic results in self-censorship to avoid jeopardizing access.

Jerusalem correspondents, reliant on Israeli officials, face even greater pressures. Critical stories risk official complaints, legal threats, and loss of entry. Editors usually require giving Israel a right of reply before publishing negative pieces. At that point, Israel or its lobby often exerts pressure to suppress stories. Editors often pull contentious articles to avoid confrontation.

Pressures from head office: Media headquarters in the US and Europe face pressure from influential lobby groups connecting Israel criticism to antisemitism. Organizations like the Anti-Defamation League and Board of British Deputies claim to represent local Jewish communities who feel “upset,” “bullied,” or “anxious” whenever Israel is challenged.

According to the Board of Deputies, BBC execs are so craven on Israel that they hurried to meet the Board to:

1) reassure it they don’t support an “antisemitic” programme the BBC had absolutely nothing to do with and that was not actually antisemitic.

2) suggest that Louis… https://t.co/kcInMgsMIx

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) November 7, 2025

The most hardened editors appear the most fearful. Media academic Greg Philo cited a senior BBC editor in 2011 describing “waiting in fear for the phone call from the Israelis.” The past two years underscore this: an extreme sensitivity to Israel-supporters yet a profound insensitivity to those standing with Palestinians facing massacre and starvation.

This leads to a much stricter threshold for publishing stories critical of Israel than for other global conflicts. Compare how readily atrocities in Ukraine are attributed to Russia, whereas many journalists hesitate to label far worse acts in Gaza as atrocities or hold Israel accountable.

Rome news agency Nova sacks a journalist for asking the European Commission why it isn’t insisting Israel pay for the rebuilding of Gaza when it demands Russia pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine.

Colleague says pro-Israel censorship in Italy is rife.https://t.co/tjH20dl4vn

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) November 5, 2025

Israeli government censorship: Many are unaware Israel operates a military censorship system restricting journalists, especially relevant given most Jerusalem correspondence covers Israel’s illegal occupation.

This can take the form of denying access—as in Gaza for the past two years—requiring journalists to embed with the military, as the BBC did during the Gaza genocide, or demanding withholding of certain crucial facts.

For example, during Israel’s 2006 war on Lebanon, I was the only journalist attempting to allude to Israel positioning tanks firing into southern Lebanon near Palestinian communities, effectively using civilians as human shields. Most journalists voluntarily self-censor to avoid conflicts with Israel’s military censor.

In one rare public mention, BBC’s Lucy Williamson, embedded with the Israeli military this month, noted that Israel’s military censors reviewed their material before publication, yet the BBC maintained editorial control.

And I have a bridge to sell you.

Israeli government control: Foreign journalists operating in Israel must carry government-issued Press Office cards. Over the last 20 years, Israel has tightened accreditation, allowing only reporters affiliated with officially “accredited” news organisations to receive passes. This restricts freelancers and independent journalists, who have found it increasingly difficult to report freely, forcing filtering of news through major outlets, which face their own limitations. Israel has effectively banned independent journalists.

Rebuilding our worldview

The power of these pressures largely stems from journalists’ fear of being branded antisemitic by Israel. While this factor is significant, I believe it often serves as an excuse, a comforting narrative to rationalize journalistic failures—such as their reluctance to acknowledge the Gaza killings as genocide.

Beyond practical barriers lies a deeper cause for western media’s avoidance of harsh critique: Israel’s central role in a continuing colonial power structure projecting western influence into the oil-rich Middle East. Israel stands as the West’s primary proxy state, making its protection a priority for western elites.

Why BBC editors must one day stand trial for colluding in Israel’s genocide.

Read my latest: https://t.co/GjHh9CbTPw pic.twitter.com/2Vu1NQkHwV

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) June 20, 2025

None of this would be so grave if our vaunted “free press” was genuinely free. Were it truly a vigilant watchdog holding political powers accountable, no politician could hide.

Instead, corporate media amplifies political elites’ agendas, effectively serving as the establishment’s publicity arm.

While at the Guardian, the foreign editor—now a leading columnist—once revealed he preferred not to keep correspondents in difficult postings like Jerusalem for long because the longer they stayed, the more likely they were to “go native.” At the time, I didn’t fully grasp this, but soon I did.

I began covering Israel-Palestine as a freelancer in 2001. Free from editorial constraints, I set up in Nazareth, a Palestinian-majority town inside Israel, hoping that this different vantage point—while my peers reported from Jewish Jerusalem or Tel Aviv—would offer unique insights and appeal to editors.

Instead, this perspective made me far less attractive and, in fact, made my editors uneasy.

The truth is it took me years to unlearn the conditioning—both ideological and professional—that had led me to view Israelis as the protagonists and Palestinians as the antagonists.

I had to reconstruct my professional framework from the ground up, like a child learning to understand new truths. Though I concealed it at the time, this was a slow, terrifying, and painful awakening that shattered all my former beliefs.

Given this, it is unsurprising that the vast majority of journalists never undergo such a transformation. They rarely gain the chance to immerse themselves fully in the lives of Palestinians or other “natives.” Nor do they have the time to step back and develop a broader understanding. They are encircled by family, friends, colleagues, and superiors who reinforce established narratives and so-called “professional” standards that guard the status quo.

They face strong disincentives to deviate from the accepted path, with the pressures of income, career advancement, bills, and family obligations.

Ultimately, embarking on such a journey means confronting a daunting, uncertain future down a dark and unknown tunnel.

Original article: www.jonathan-cook.net