For Netanyahu, having a cooperative Venezuelan government could serve as leverage against certain integration frameworks that oppose his interests.

Why has the U.S. Navy taken a menacing stance toward Venezuela without launching a direct assault? To unravel this, one must look in a few predictably surprising places. Consider last October, when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood among the first to personally congratulate Venezuelan opposition figure María Corina Machado upon her Nobel Peace Prize win. Only two other major leaders followed suit: Milei from Argentina and Merz from Germany—both known for their unwavering support of Likud policies and Israel’s Gaza war. Why was Machado singled out by this distinct trio?

The official rationale claims Machado aims to root out covert Hezbollah cells backed by Iran hiding in Venezuela’s jungles. Yet, most observers dismiss this as implausible—a narrative reminiscent of a poorly crafted 1980s Hollywood B-movie. Instead, Netanyahu’s focus on Venezuela likely revolves around oil—Israel’s need to diversify its energy sources while gaining bargaining power over Gaza if he challenges the ceasefire and UN Security Council Resolution 2803, even if it risks regional economic normalization. Highlighting alternatives like Venezuela grants Israel flexibility to obstruct a Gaza peace deal, even if political fallout disrupts current oil supplies. Does Trump share Netanyahu’s approach, or is another dynamic at play?

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, about 303 billion barrels as of 2024, surpassing Saudi Arabia. During her interview with Donald Trump Jr, Machado stressed that Venezuela’s reserves outstrip Saudi Arabia’s and spoke in remarkably colonial terms about opening Venezuelan oil to unfettered exploitation by American interests. Did she intend exclusively American access? To grasp Venezuela’s situation, one must consider the ongoing tensions between Netanyahu, Trump, and MbS over Gaza peace and normalization.

Israel’s Limited Options: Two paths

Israel’s future moves in economy, energy, and security hinge on two main paths: continuing reliance on European and Western allies or fully integrating into the regional economy. The first option preserves existing regional alignments but is economically inefficient. Without new supply sources like Venezuela, Israel risks stagnation while regional counterparts grow stronger, enhancing Saudi leverage. This explains Tel Aviv’s pursuit of IMEC and normalization efforts. Accessing cost-effective Venezuelan oil could delay regional integration or bolster Israel’s negotiating stance.

The second option involves embracing regional economic integration, expanding the Abraham Accords, and normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia, which generally favors Israel. It would strengthen Western partnerships but weaken Netanyahu’s negotiating position and force a politically sensitive domestic course, alienating hardliners who view Gaza as integral to Israeli settlement and annexation goals.

IMEC and the Saudi factor

To enhance its position as a transit hub and secure Saudi oil access, Israel seeks better pricing and supply terms than current sources offer. Recognizing the necessity to shift regional orientation, particularly regarding Saudi Arabia, Israel acknowledges Riyadh won’t normalize relations or join the Abraham Accords without Gaza peace and redevelopment, consistent with the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative and conditional on Trump’s 20-point plan’s success.

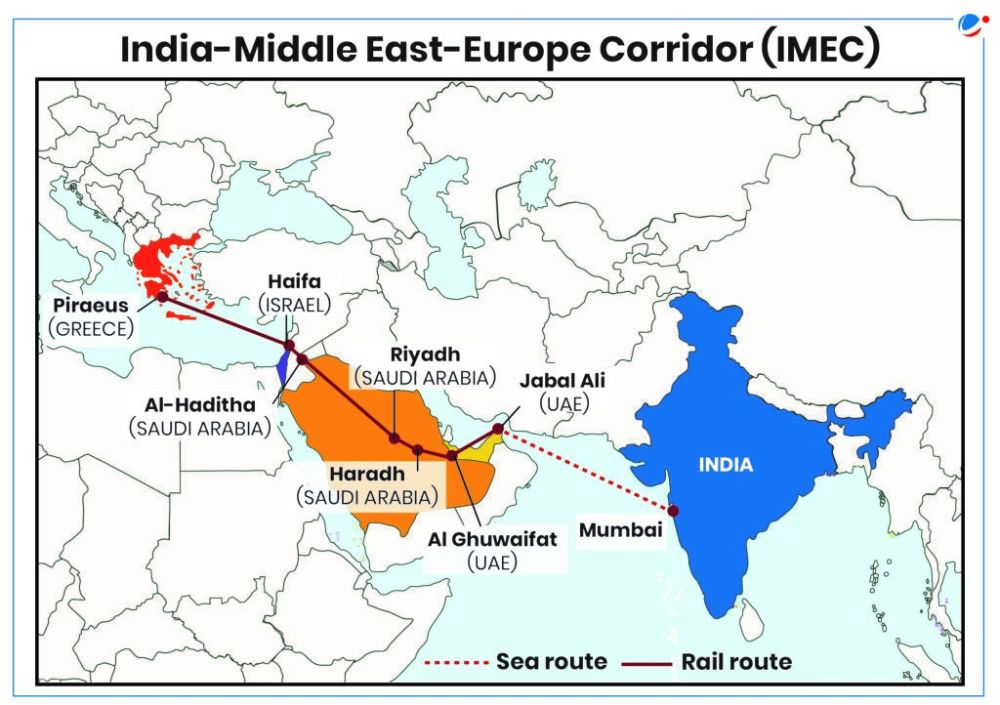

Israel has proposed a direct oil pipeline route from Saudi Arabia to Europe through Israeli territory, as revealed by Minister Eli Cohen. The proposal features a 700-kilometer pipeline to Eilat, continuing via the Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline Company (EAPC), often called the “Europe-Asia Pipeline,” and reaching European markets through the Mediterranean via Cyprus and Greece. Cohen pitched this as a means to expand the Abraham Accords and enhance Israel’s strategic and economic stature, but it critically depends on Saudi normalization—something the IDF’s Gaza incursion severely undermined. This plan is a major piece of IMEC (India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor), a project Israel views with both enthusiasm and caution.

Through the Abraham Accords, Israel hoped to normalize and become the primary conduit for Indian goods and Mid-East energy exports into Europe under IMEC. Yet Saudi Arabia refuses normalization without concessions on Gaza, blocking IMEC’s success unless Netanyahu agrees to the 20-point plan. Both Israel and Saudi Arabia desire IMEC, but only the Saudis face geographic constraints. India is supportive but can manage without Israel if necessary to bypass trade barriers.

IMEC infographic credit: www.imec.international

Israel views IMEC as vital to its strategic and economic future but lacks full control over the corridor’s design. The Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, might reroute energy exports through Gaza rather than Israel, reducing Israel’s influence. This scenario would see pipelines and transit infrastructure bypass Israeli lands, leaving it with diminished sway over energy and commerce. This highlights Israel’s dependence on Gulf cooperation and compromises on Gaza and Palestinian normalization to benefit from IMEC.

If the IDF had succeeded in Gaza with political gains and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, Gaza would have become de facto Israeli territory, removing Gaza as an alternative transit hub independent from Israel. This might partially explain Netanyahu’s strategy in the failed Gaza offensive.

Saudi Arabia may also have alternative options. Historically, Saudis operated an oil pipeline directly to Lebanon, TAPLINE, launched in 1950. It carried Saudi crude across Jordan and Syria to the Mediterranean for export, offering a way to avoid shipping through the Suez Canal. Built by American-controlled Aramco-related companies, it once promised to reshape Levantine geopolitics.

However, Syria severed the pipeline during the 1967 conflict to penalize Saudi Arabia for its U.S. ties, crippling the line. Recent governmental changes in Syria alter that dynamic.

TAPLINE route in the 1950s

Israel confronts the same challenge whether importing Saudi oil or sustaining its current supplier network: setbacks in Gaza peace and renewed hostilities will derail Saudi plans and likely prompt Brazil and Turkey to intensify hesitation into concrete cutbacks or suspension.

Israel’s Gaza war seriously complicates IMEC. Analysts argue the conflict undermines the corridor by halting normalization talks between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Venezuela already suits Trump’s interests

Whether Trump truly desires regime change in Venezuela remains uncertain. Justifying it is difficult, given the current arrangement favors Trump. Chevron runs profitable operations in five Venezuelan locations under Maduro’s government, holding 30%-40% stakes in joint ventures with PdVSA. Some sanctions were eased temporarily due to Treasury’s OFAC exemptions during summer and as late as August 2025 under Trump’s administration, facilitating ongoing business. The alignment between Maduro and Trump at present inspired our article “Are Trump and Maduro secretly friends? Smoke & mirrors in 47’s win-win game in Venezuela.”

Another perspective cannot be overlooked. The U.S. benefits from the current Venezuelan setup. By vilifying Caracas, Washington conceals a practical arrangement wherein only the U.S. can purchase Venezuelan crude at standard prices, effectively receiving deeper discounts since transactions are settled with refined products valued at retail for Venezuela. Other nations pay significant premiums, as any non-U.S. buyer incurs a 25% tariff atop current tariffs. Effectively, Venezuela acts as a quasi-private oil reserve for the U.S., both less costly and more secure than headline crises suggest.

Supporting evidence follows.

According to Venezuela Analysis in early August:

“U.S. oil company Chevron is poised to resume crude exports from joint ventures in Venezuela after a renewed U.S. Treasury sanctions waiver, confirmed by CEO Mike Wirth Friday[…]

‘This month, some oil is expected to start flowing to the U.S. from our Venezuelan operations,’ […]

Wirth noted the restart would have a modest short-term effect on profits but aid debt recovery. He lobbied extensively for Trump administration approval and reaffirmed Chevron’s commitment to U.S. sanctions compliance.

Confidential sources told Reuters a specific license was issued, distinct from general licenses and not publicly posted by Treasury.

”

Bloomberg recently reported that Chevron’s CEO Mike Wirth stated that the firm, the sole major U.S. oil company remaining in Venezuela, intends a long-term presence and plans to assist rebuilding when feasible. This ambiguous stance signals ongoing operations without committing to any particular political outcome.

ExxonMobil exited Venezuela following nationalization reforms decades ago but could potentially return. The U.S. could lift sanctions anytime but must manage oil prices and OPEC balance carefully.

Restricted Venezuelan crude typically supports higher global barrel prices. Saudi Arabia, as OPEC’s largest producer with spare capacity, benefits from this as it sells more crude at elevated prices without losing market share. In essence, U.S. sanctions on Venezuela inadvertently boost U.S. and Saudi revenues by limiting supply while granting Riyadh greater control over OPEC production and pricing.

Important context: Venezuela produces about 900,000 barrels per day (bpd), while Saudi Arabia produces roughly 9 million bpd. Venezuelan reentry to global markets would lower prices, working financially against major exporters like Saudi Arabia and the U.S., which exports about 4 million bpd of its 13.5 million total production.

Trump may still hope to reshape Venezuela’s political landscape or increase Chevron’s joint venture share with PdVSA, possibly bringing ExxonMobil back. Maduro seems open to cooperation. Yet U.S. energy companies already maintain access, and sanction removal depends solely on Washington. Venezuela continues handling dollars and conducts most oil trade in USD, with $17.5 billion in sales projected for 2024. What additional benefits would regime change yield? Without direct U.S. intervention, success is unlikely; a military strike would ruin oil infrastructure and entangle the U.S. in hazardous troop deployments. Chevron prioritizes commerce over conflict and currently does not advocate regime change.

Indeed, U.S. imports of Venezuelan oil rose in 2025, hitting about 250,000 barrels per day in January—some of the highest levels since 2019 sanctions began. Tanker tracking shows exports reaching a nine-month peak in August, with nearly 60,000 bpd destined for the U.S. Gulf Coast. This growth mainly stems from Chevron’s operational resumption under U.S. license, confirming direct Venezuelan supply links to American refineries, as the U.S. receives 37% of Venezuela’s crude output.

In hindsight, the existing arrangement appears reasonably stable; prices are consistent, and Saudis seem satisfied. Venezuela receives payment in kind from joint ventures, as CNN reported, likely in barrels:

“In July, the Trump administration reissued a license allowing Chevron to export Venezuelan crude, with new terms permitting payment of fees and royalties in oil rather than cash, effectively halving Chevron’s crude exports from Venezuela, according to Reuters.”

Thus, Trump’s naval escalation and eagerness for regime change in Caracas fail to align clearly. The current Venezuelan setup satisfies both the U.S. and oil producers, with Caracas preferring stability over regime overthrow or war. What other factors might be influencing this?

Closing thoughts

For Netanyahu, a Venezuela willing to cooperate could provide leverage over integration frameworks that clash with his objectives, at least offering a credible alternative.

Israel depends on oil from routes passing through Turkey—either from Azerbaijan, Russian-linked Kazakhstan, or Brazil—routes threatened by Netanyahu’s aggressive Gaza policies. Israel also carries a strategic energy mandate. Evidence suggests Turkey has already acted. Part II will explore these threads, detailing Israel’s energy dynamics, the constraints on Netanyahu’s Gaza policy, and why a steady Venezuelan heavy crude supply under Machado’s arrangement would resolve issues the United States prefers remain unresolved, actively opposing such solutions.

The forthcoming installment will delve into the specifics of Machado’s understanding with Netanyahu and explain the strategic reasoning behind the U.S. Navy’s unusual deployments around Venezuela, including withdrawals from the Eastern Mediterranean and Persian Gulf. Introducing Venezuela to Israel via a U.S.-facilitated regime shift would undermine Trump’s Gaza plans by offering Israel an alternative path, yet the carrier group remains poised nearby.

Follow Joaquin Flores on Telegram @NewResistance or on X/Twitter @XoaquinFlores