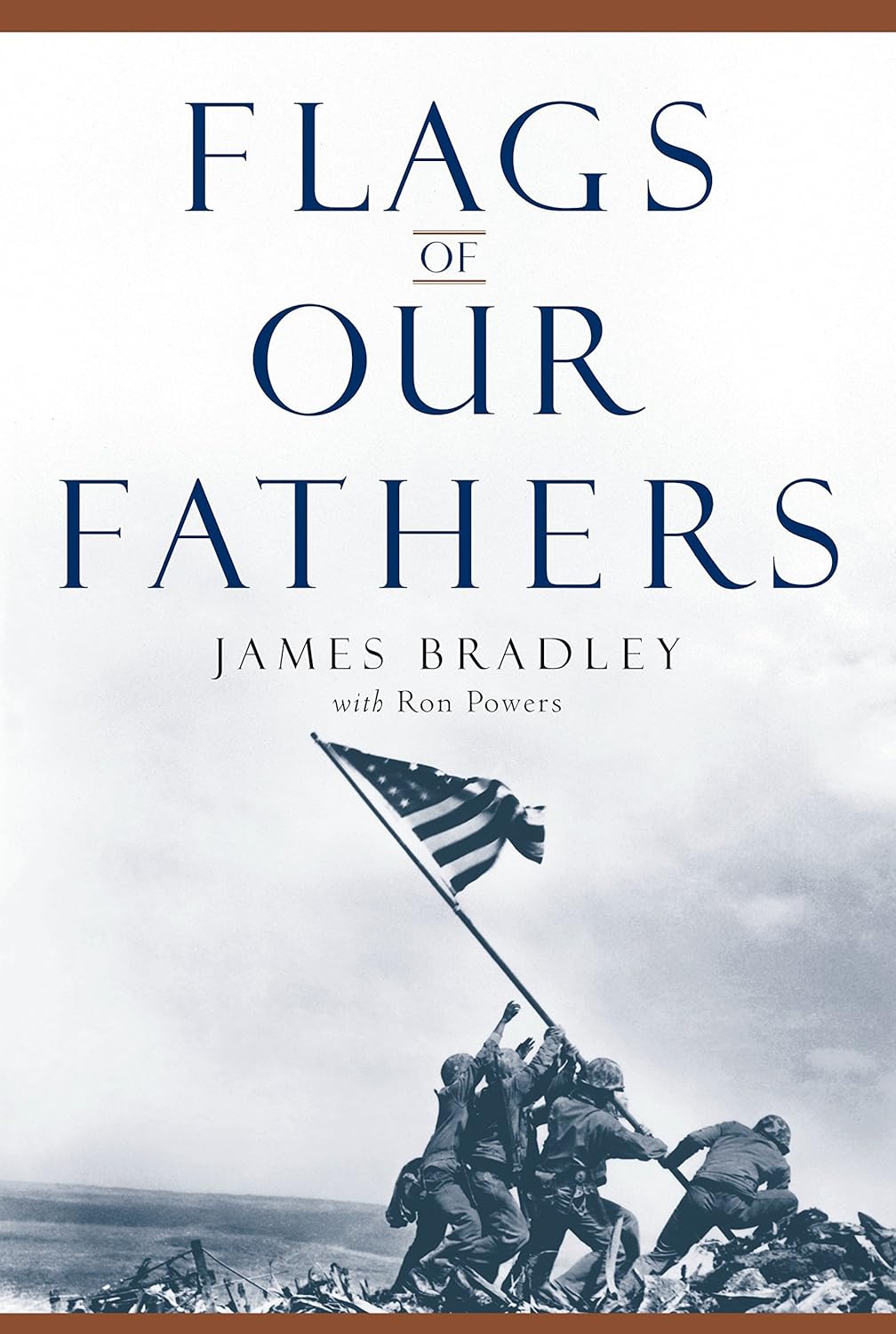

The son of the Iwo Jima flag-bearer featured in one of America’s most iconic photographs, James Bradley rose to prominence with his 2000 book Flags of Our Fathers, later adapted into a film directed by Clint Eastwood.

Displeased by how Flags of Our Fathers was co-opted to evoke nostalgia for World War II and glorify the so-called “greatest generation,” Bradley shared with me that his intention was to create an anti-war narrative reflecting the harsh realities faced by his father John and fellow Iwo Jima flag-bearers, along with the lasting psychological scars they endured.

In the past ten years, Bradley noted that mainstream media has largely ignored him because his works critically evaluate U.S. foreign policy in Southeast Asia.[1]

Bradley’s newest release, Precious Freedom: a novel (New York: Skyhorse, 2025), is a compelling contribution emphasizing anti-war themes and a critical view of American foreign policy, especially regarding the Vietnam War and America’s defeat.

A talented storyteller, Bradley spent a decade living in Vietnam and interviewed key figures from the Vietnamese government and the National Liberation Front (NLF, or Vietcong) to deepen his understanding of the conflict.

Precious Freedom confronts the rising trend of revisionist history that claims the U.S. might have won the Vietnam War had it employed different military strategies and that its involvement represented a fundamentally noble cause.

Part of this notion stems from the belief that the South Vietnamese government genuinely upheld democratic ideals and had broad public backing.

In stark contrast, Precious Freedom exposes South Vietnam as a fabrication of U.S. policy—a “Potemkin state.”

The Vietnamese population largely viewed their country as a unified entity and resisted American forces and their collaborators in pursuit of national reunification.

The South Vietnamese leadership lauded by revisionists depended heavily on U.S. aid, had longstanding ties to the French colonial regime, favored the Catholic minority, and brutally repressed political challengers.

Those fighting alongside them were predominantly seen as traitors aligned with the latest foreign invaders.

Bradley points out that although the Vietnamese are peace-inclined, throughout history they have mobilized fiercely against occupying powers—including the Chinese, Mongols, French, and Americans.

The deep veneration for Ho Chi Minh is evident, with many Vietnamese households displaying his portrait alongside his foremost military commander, General Vo Nguyen Giap, who masterminded victories over the U.S., France, and Japan.

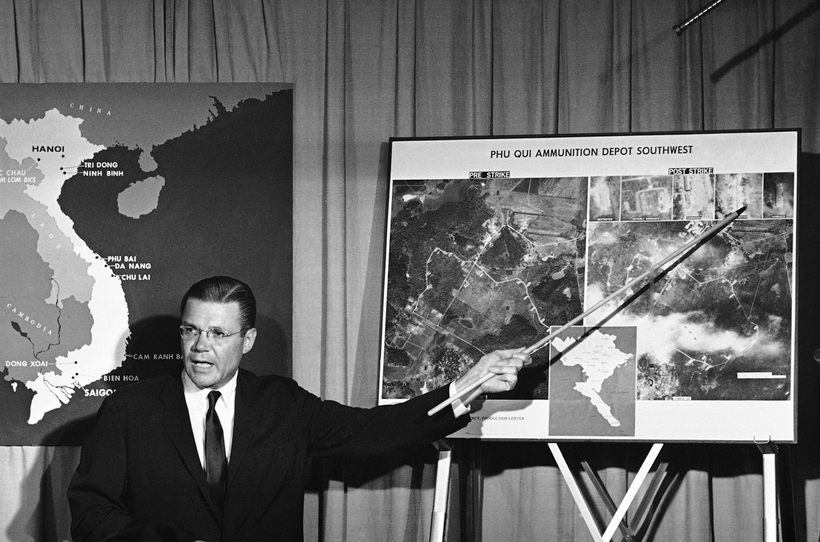

Conversely, portraits of Lyndon B. Johnson, William Westmoreland, or Robert S. McNamara—principal architects of the American war effort—are rarely displayed in the U.S., as these figures are often regarded as deceitful, incompetent, and responsible for grave war crimes.

McNamara himself acknowledged his mistakes in his memoir, confessing that when directing troop deployments to Vietnam, he had limited knowledge of the country.

[Source: amazon.com]

Bradley interprets McNamara’s heartfelt confession as encapsulating the core reason behind America’s loss in Vietnam—the failure to comprehend their adversary and the motivations driving them.

The misconception was that the U.S. intervened to save South Vietnam from communist aggression originating in the North.

This is illogical considering Vietnam’s division was artificial, and the people consistently viewed themselves as members of a single nation.

Notably, the Eisenhower administration declined to honor the 1954 Geneva Accords, which after a temporary partition, had planned nationwide elections for unification in 1956.

Those elections never occurred because, as Eisenhower admitted, Ho Chi Minh was expected to win overwhelmingly.

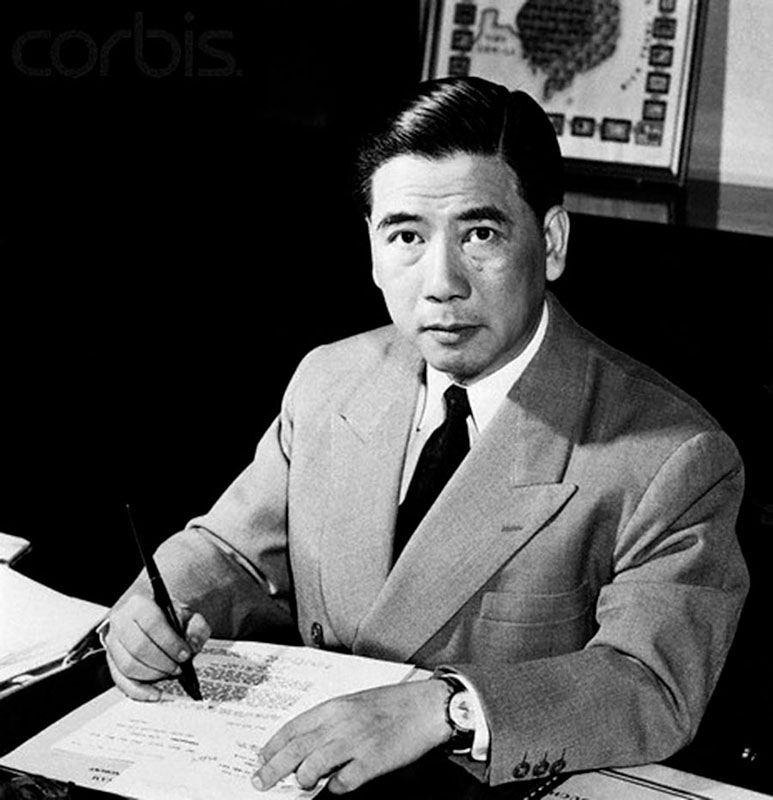

Rather than proceeding with elections, the U.S. backed a regime headed by anti-Communist Catholic Ngo Dinh Diem, who alienated Buddhists and sparked a guerrilla insurgency through his imprisonment and brutal treatment of opponents and former anti-French fighters.[2]

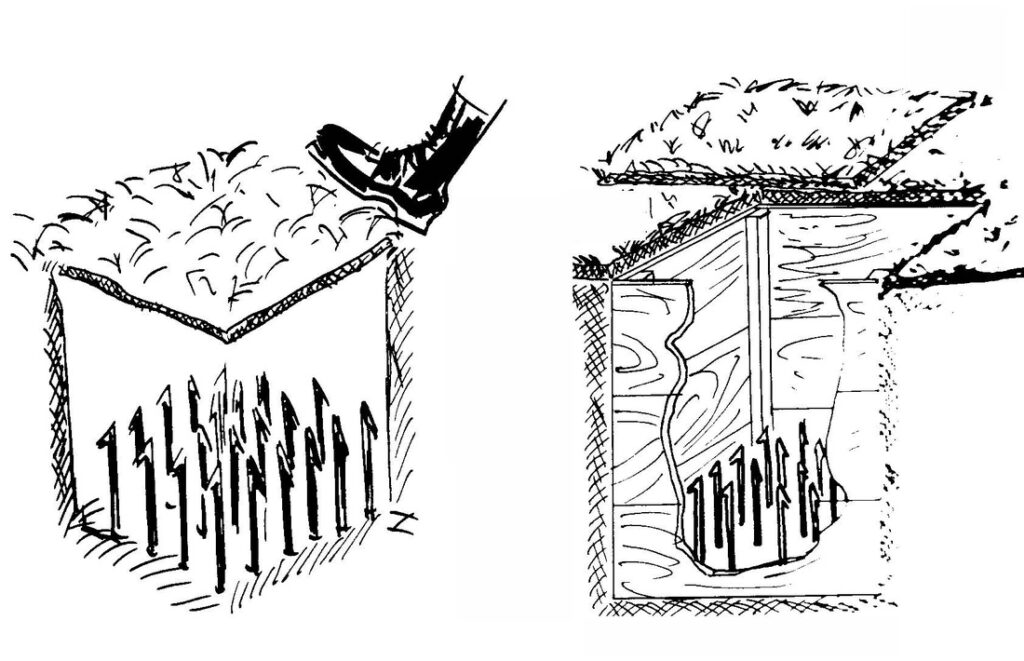

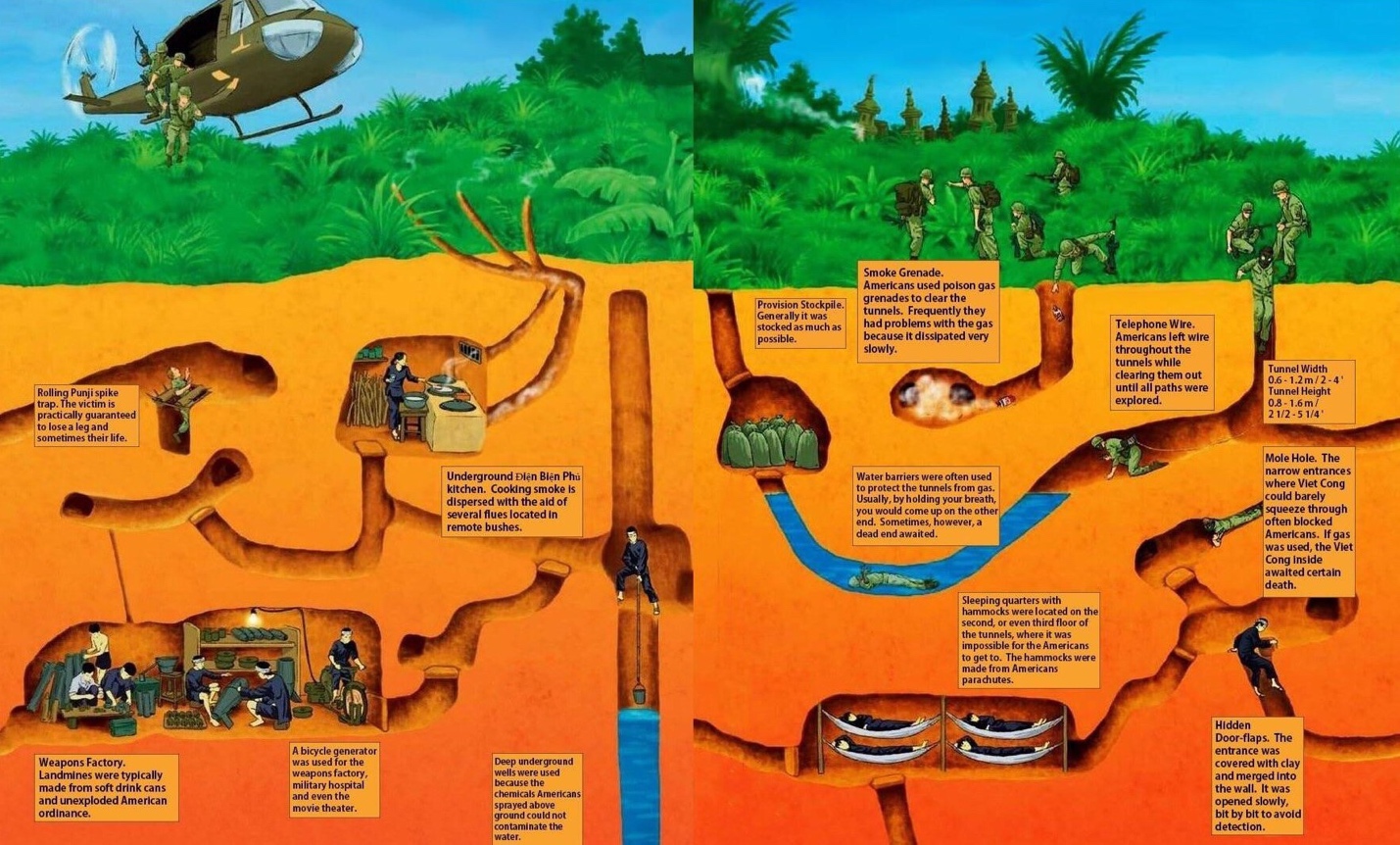

Having honed guerrilla warfare against French, Mongol, and Chinese forces, the Vietnamese countered American technological superiority using ground traps, elaborate tunnel systems, and nocturnal ambushes.

Armed mainly with simple weapons capable of shooting down helicopters, the Vietnamese fully leveraged their intimate knowledge of jungle terrain and relied on espionage to anticipate U.S. operations.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail stands as an impressive feat of engineering, facilitating the movement of troops and supplies through the North-South axis while circumventing the heavily fortified Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

Bradley highlights that the Vietnamese possessed an unmatched commitment and unity that their American adversaries and allies lacked. A popular saying among the Vietnamese is “when the foreigner puts even one foot on Vietnamese soil, everyone stands up, including the women.”

His narrative focuses on two invented characters: Chip Zobel, a soldier from rural Minnesota, and Hoang Thi May, a female NLF sniper and fighter. May joined the NLF at age 15 after witnessing Chip kill her father.

Bradley outlines Zobel’s rural Catholic upbringing in a family deeply influenced by the dominant Cold War mindset of the 1950s and 60s.

Chip’s father, Hank, fought at Saipan during the Pacific War, and two of his uncles served in Korea.

As an altar boy attending Mass with his parents, Zobel was taught that communism was a destructive force and that he had to combat its spread in Vietnam.

In his youth, he was influenced by the writings of Tom Dooley, a missionary doctor who recounted alleged atrocities committed by Vietnamese communists after the First Indochina War.

Unbeknownst to Zobel, Dooley was actually a CIA operative spreading propaganda.

During basic training, Zobel was transformed into a professional warrior.

Upon arriving in Vietnam, he and his comrades brutalized Vietnamese people, derogatorily called “dinks” and “gooks.”

In certain villages, Zobel’s peers committed atrocities, including rape and murder.

Zobel was haunted by the killing of May’s father and suffered from nightmares throughout his life.

Like many veterans, he became disenchanted with the war and came to realize it was founded on falsehoods.

His wife, Mary, gave birth to a stillborn child; Chip himself was rendered infertile due to exposure to Agent Orange.

Overcome with despair and a sense of betrayal by leadership and society, Chip ended his life in 2008 by shooting himself in the heart.

In contrast, May’s life turned out more peacefully. After the war, she became a history teacher and is now a grandmother.

After Chip killed her father in 1967, May sought revenge and was directed to the jungle to meet “Mr. Son,” a nephew of Pham Van Dong, one of Ho Chi Minh’s trusted revolutionaries, who trained her as a guerrilla fighter.

Despite enduring harsh jungle conditions, May found the task of killing Americans easier due to their loudness and tendency to travel in groups.

Ironically, both May and Zobel were wounded during a river engagement.

Both survived, but only May found peace as she had fought for a just cause.

While May’s son served overseas, Chip’s mother Betty began delving deeper into Vietnam War history. She discovered Tom Dooley’s true role as a CIA agent, realizing she and her son had been misled.

A close librarian friend named Kathryn, who shared articles with Betty, tragically lost her son Billy to a mistaken U.S. napalm strike.

The conclusion of Precious Freedom features an emotional encounter where Claire, Chip’s sister at age 62, visits May and apologizes for her brother’s wartime actions.

Having been a teen during Chip’s deployment, Claire was moved by May’s compassion and forgiving nature.

May conveyed a teaching of Ho Chi Minh—that the Vietnamese should not harbor hatred toward American soldiers, who acted as government agents, often misled about the truth.

During their visit, Claire and author James Bradley, who appears in the story’s conclusion, tour historical sites: Con Dao Island’s notorious U.S.-run prison with bamboo cage torture; the Cu Chi tunnels constructed by the NLF to withstand bombings; and the grave and museum honoring Vo Thi Sau, a Vietnamese heroine executed by French colonialists at 19.[3]

Bradley stresses that those who argue “America could have won the Vietnam War if only” should visit these places and engage with Vietnamese people to better grasp the war’s complex realities.

The majority of Vietnamese fighters opposing the U.S. were not driven by communist ideology but were nationalist guerrillas resisting invaders who destroyed communities, forced civilians into “strategic hamlets,” and killed family members.

Bradley critiques American historical narratives that wrongly suggest the U.S. controlled significant territory or achieved military victories, despite advanced technology and air supremacy.

The massive bombing campaigns and Agent Orange spraying caused vast destruction but failed to diminish the popular backing for nationalist guerrillas.

Regrettably, Americans continue to be misinformed about the Vietnam War, leading to repeated catastrophic interventions in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Gaza, and Ukraine.

These nations have similarly suffered from warfare either led or supported by the U.S., exacting an immense human toll.

***

1) These texts include: a) Flyboys: A True Story of Courage (Boston: Back Bay Books, 2004), which recounts U.S. Air Force pilots, including George H. W. Bush, involved in a bombing mission over Iwo Jima; b) The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War (Boston: Little, Brown, 2009), detailing a diplomatic expedition led by Secretary of War William Howard Taft that laid the foundation for U.S. imperial influence in Asia-Pacific; and c) The China Mirage: The Hidden History of American Disaster in Asia (Boston: Back Bay Books, 2016), covering misguided American views on China and domestic consequences from the 1949 Chinese Revolution. ↑

2) A group of revisionist historians, some teaching at prestigious universities, have attempted to recast Ngo Dinh Diem as a commendable leader wrongfully overthrown in the 1963 CIA-backed coup. ↑

3) The prison was managed by Frank Walton, a former LAPD deputy chief with racist views, employed by USAID’s Office of Public Safety (OPS), who once described Con Son Prison to congressional visitors as resembling a “boy scout recreational camp.” ↑

Original article: covertactionmagazine.com