DUNHUANG – Throughout history, the Silk Road — more accurately a series of interconnected routes — stands as the ultimate artery of connectivity, threading through Ancient Eurasia and linking what Chinese academics unanimously recognize as the world’s core civilizations: China, India, Persia, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. This extensive network also chronicles numerous phases of economic and cultural interaction between East and West.

Professor Ji Xianlin, a distinguished expert on Dunhuang, coined a phrase that remains provocative to Western supremacist viewpoints:

“There are only four, rather than five, influential cultural systems in the world: Chinese, Indian, Greek and Islam. They all met only on China’s Dunhuang and Xinjiang”.

Thanks to its pivotal location, Dunhuang naturally became a site of extraordinary artistic developments.

After several years since my last visits, compounded by the Covid pandemic and China’s steady rebound, I was fortunate to undertake a refreshed Journey to the West, tracing the original Ancient Silk Road from Xian — the historic imperial capital Chang’an — through the Gansu corridor to Dunhuang.

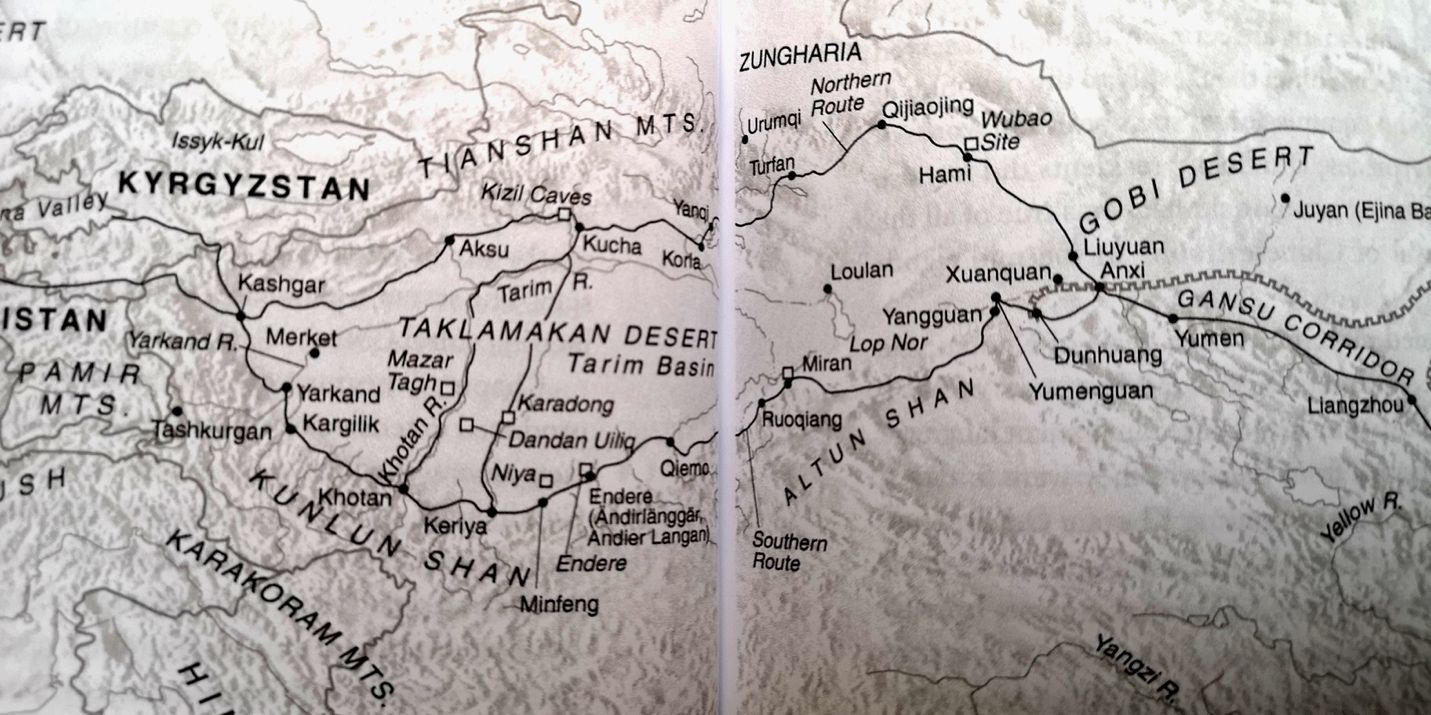

Various magnificent Eurasian cultures met, mingled, and flourished along these Ancient Silk Roads. Situated at the western edge of the Hexi corridor in Gansu province, Dunhuang served as the foremost hub on the eastern segment of the Chinese Silk Road. It is bounded by mountain ranges to the north and south, the central plains to the east, and Xinjiang to the west.

Known as the “Blazing Beacon,” Dunhuang held immense strategic importance as it controlled two key passes: Yangguan and Yumenguan. Han Emperor Wu Di recognized that Dunhuang provided the final significant water source before the daunting expanse of the Taklamakan desert, and it controlled the main three Silk Road paths extending westward.

Yumenguan, or the Jade Gate pass, established by the Han Empire in the 2nd century B.C., lies at the western fringe of classic China in the southern Gobi and the western terminus of the Qilian mountains.

The Jade Gate Pass. Photo: Pepe Escobar

I spent an entire radiant, cloudless day exploring the pass and nearby areas after arranging transport with a Dunhuang taxi driver. It was fascinating to witness how the Han dynasty created a comprehensive system involving traffic management, beacon fires, and the Great Wall defenses (with remnants of the Han Wall still standing), ensuring the safety of the vast Silk Road.

The remains of the Great Han Wall. Photo: P.E.

Engage the caravan: the essence of “people to people’s exchanges”

At the meticulously maintained Dunhuang Book Center, historical accounts describe it as “a metropolis where the Han people and non-Han peoples meet.” This city served as an early model for what Xi Jinping calls “people to people’s exchanges.” This ethos still persists vividly, particularly at the vibrant Night Market, renowned for its Uyghur culinary specialties.

Uyghur businesswomen at the fabulous Dunhuang Night Market. Photo: P.E.

Silk and porcelain from the central plains, perfumes and jewelry from the “western regions,” camels and horses from northern China, and grains from Hexi—all these items changed hands in Dunhuang. Trade negotiations, migrations, military exercises, and cultural interactions alongside scholars, officials, artists, diplomats, pilgrims, and soldiers transformed traditional Chinese culture into a vibrant blend incorporating Sogdian, Tibetan, Uyghur, Tangut, and Mongolian elements, all reflected in Dunhuang’s art heritage.

Religions such as Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Islam gradually influenced Dunhuang’s artistic expressions via architecture, sculpture, painting, music, dance, and craftsmanship including weaving and dyeing techniques from Central and West Asia.

In the context of Xi’s vision for a “moderately prosperous” and modernized China, the phrase “Silk Road” carries subtle implications. For example, in Xian at the Small White Goose Pagoda, it is depicted as “Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang’an-Tian Shan corridor,” emphasizing the Tian Shan mountains rather than the politically sensitive Xinjiang region, historically known as the “western regions” and not necessarily controlled by China for many centuries.

Concerning the origins of the Silk Road, the widely accepted historic version credits Han Emperor Wu Di with dispatching Zhang Qian, the first official Chinese envoy, to the “western regions” around 140 B.C. According to the “Records of the Grand Historian,” Zhang Qian’s diplomatic missions opened communication lines, enabling Han China to initiate trade relationships with states across the northwest, particularly exchanging silk.

Between Xian’s Shaanxi History Museum, the Dunhuang Academy, and the Gansu Museum in Lanzhou, conversations with scholars and curators complement the impressive Silk Road exhibitions. The official story emphasizes how “the civilization of ancient China represented by silk started to impact the states in the western regions, Central Asia and West Asia.”

However, the reality was far more intricate. Alongside silk, items such as spices, metals, chemicals, saddles, leather goods, glassware, and paper (invented in the 2nd century B.C.) circulated widely. Yet the central theme remains: merchants from China’s heartland braved deserts and mountains carrying silk, bronze mirrors, and lacquerware, hoping to barter for rare goods, while traders from the western regions supplied furs, jade, and felts in return.

This was a genuine example of multiethnic “people to people’s exchanges.” Incidentally, the term “Silk Road” itself was never used historically; instead, it was known as “the road to Samarkand” or the “northern” and “southern” paths circumventing the formidable Taklamakan desert.

Regarding the Tang dynasty currency system…

By the 3rd century, Dunhuang had reached the peak of its Silk Road prominence, which coincided with merchants and pilgrims funding the construction of the nearby Buddhist Mogao Caves.

The main pavilion at the Mogao caves. Photo: P.E.

Located within Gansu as part of the five Dunhuang grottoes, Mogao is comprised of 813 surviving caves, 735 of which belong to the Mogao system. Reaching Mogao is an adventure: visitors must take an official park bus packed with numerous tourists, journeying through the desert before arriving at the eastern base of the Mingsha mountains, bordered by the Dangquan river ahead and the Qilian mountains to the east. The caves are carved deep into the cliff, linked by ramps and walkways.

These caves were initially constructed from the 4th to the 14th century, with the earliest murals dating back to the 5th century. Spread over four tiers and extending 1.6 km north to south along cliffs up to 30 meters high, the southern sector’s 492 caves contain more than 45 km of wall paintings, over 2,000 painted statues, and five wooden eaves. The initial purpose was devotion to Buddha.

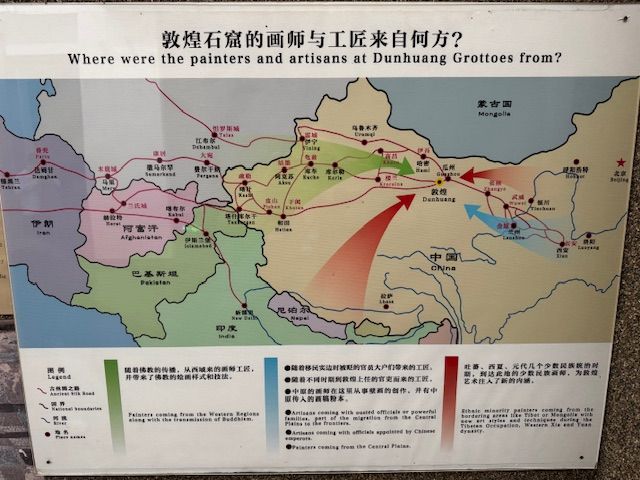

At the Dunhuang Academy museum: where the artists came from. Photo: P.E.

The artworks currently visible are breathtaking. Standouts include a wrestling scene from Buddha’s life in cave 290; a girl apsara dancer in cave 296; the Deer King in cave 257; a hunting scene in cave 249; a Garuda figure called “the Scarlet Bird” in Chinese in cave 285; parables from the Magic City in the Lotus Sutra on cave 217, exemplifying High Tang dynasty artistry; a seated Bodhisattva in cave 196; and exquisitely preserved worshippers of bodhisattvas in cave 285.

One of the Buddha highlights of the Mogao caves. Photo: P.E.

Strict guidelines govern visits: only specific caves may be entered accompanied by an official guide; photography is forbidden and only the guide’s torchlight is allowed for illumination. I was fortunate to be led by Helen, a Dunhuang University alumnus currently pursuing a PhD in Archaeology, who later detailed the groundbreaking preservation efforts at the Dunhuang Academy.

Constructing the caves demanded remarkable coordination: chisellers carved out caves; stonecutters dug further chambers; bricklayers built wooden or earthen structures; carpenters crafted and mended wooden implements; sculptors created statues; and painters adorned caves and statues with vivid artwork.

Mogao remains unmatched as an aesthetic treasure trove of Buddhist murals, blending Chinese, Persian, Indian and Central Asian artistic traditions.

Beyond what visitors see lies the lost library cave, containing over 40,000 scrolls — the largest cache of Silk Road documents and artifacts ever found. These scrolls span texts on Buddhism, Manicheism, Zoroastrianism, and the Eastern Christian Church from Syria, a testament to Dunhuang’s cosmopolitan character. The removal of these treasures by European scholars and collectors in the late 19th century constitutes a complex and lengthy tale of plunder.

Economically, Dunhuang flourished for nearly a millennium, particularly during the Tang dynasty (6th to 9th centuries). The Tang had a unique monetary system involving three currency types: textiles (silk and hemp), grain, and coins.

Chang’an’s imperial capital centralized trade using an aggregate unit, while Dunhuang served as a critical garrison where taxes were paid in six varieties of woven silk. Each region contributed taxed cloth reflecting local production. Tang officials transferred these fabrics to Dunhuang, where garrison commanders converted the textiles to coins and grain to remunerate merchants and supply soldiers.

In essence, the Tang dynasty steadily infused Dunhuang’s economy with wealth, primarily through woven textile taxation. This exemplifies a public-private developmental strategy that no doubt resonated with policymakers who later devised the 2013 New Silk Roads initiative in Beijing.