The future of the former “Western Regions”: an energy-rich, multi-cultural, multi-religious, geostrategic New Silk Road hub of “moderately prosperous” China.

YUTIAN, ON THE SOUTHERN SILK ROAD – Traveling through southern Xinjiang, after negotiating the vast sand dunes of the Taklamakan to visit Daliyabuyi—a remote “lost tribe” village in the heart of the desert—we returned to a state-of-the-art hotel in the oasis town of Yutian. It was midnight, and after enjoying an extensive Uyghur meal, the next impulse was simple: a shave.

One advantage of working on a documentary with a skilled Uyghur production crew, including knowledgeable drivers, is they have an insider’s understanding of the region. “No problem,” one driver assured. “There’s a barbershop right across the road.” Actually, the boulevard glittered late into the night with shops still open—life in Uyghurstan carried on uninterrupted.

My companion Carl Zha and I crossed the street to find ourselves immersed in a vibrant slice of Uyghur culture, hosted by two young barbers and their companion—a sharp youngster engrossed in a smartphone video game, seemingly in charge of local affairs with streetwise savvy.

The trio shared insights on their everyday lives, business rhythms, living expenses, sports interests, local social life, romantic pursuits, and hopes for the future. They were neither concentration camp survivors nor victims of forced labor. Spending over an hour with them felt like an interactive crash course in Uyghur society, complemented by Carl’s haircut and my shave—for under $10 at most in the early morning hours.

The following day, we continued our exploration by completing a Silk Road triad: Silk, Jade, and Carpets. We witnessed traditional silk and carpet production, techniques preserved for centuries, in the legendary oasis of Khotan.

Carpet weaving in Khotan. Photo: Pepe Escobar

Meanwhile, Yutian offered a less renowned but highly advanced jade industry, managing all phases from mining to exquisite finishing, including the prized black and white jade varieties.

Polishing the finest jade in Yutian. Photo: P.E.

In reality, the Silk Road quartet expands with an addition: knives from Yengisar—the global center for ornately crafted blades. For Uyghur men, a knife symbolizes manhood and is essential for slicing succulent Xinjiang melons whenever possible.

Yengisar: the knife capital of the world. Photo: P.E.

While traversing the Northern Silk Road, we remained vigilant to spot signs of forced labor or concentration camps for reporting to Western intelligence. Instead, en route from Kucha to Aksu, we encountered a woman working amid cotton fields.

The lady in the cotton fields. Photo: P.E.

In conversation, she explained she wasn’t harvesting cotton by hand; rather, she was clearing space for machines maneuvering to pick cotton—a mechanized farming process. A local Uyghur, she’d spent nearly twenty years on this privately owned cotton plantation, supporting her family with a fair wage. She had never witnessed forced labor camps personally.

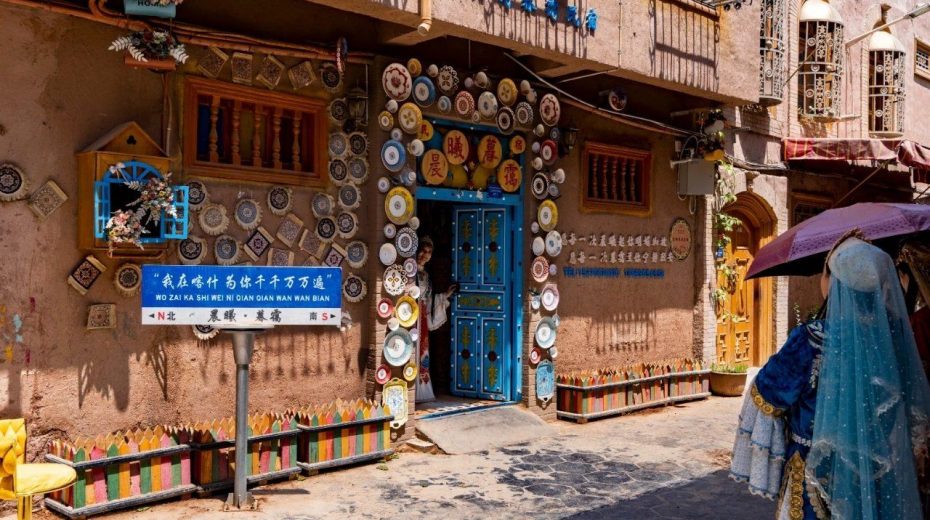

Enjoying real Uyghur life in oasis towns

Throughout both the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, in historically significant oasis settlements like Turfan, Kucha, Khotan, and Kashgar, we observed authentic Uyghur day-to-day experiences, introduced and embraced by local Uyghurs themselves, with no political topics arising.

We were welcomed into expansive homes featuring large courtyards and vine-covered rooftops. We attended two weddings—one modest celebration at a four-star hotel, and another lavish event resembling a Bollywood spectacle at Kashgar’s premier restaurant.

Over the top Uyghur wedding in Kashgar. The bride and groom are sitting right behind “Love”. Photo: P.E.

We engaged with barbers, bakers, bazaar merchants, and entrepreneurs. Sampling their unique cuisine was a delight—indeed, understanding life’s essence felt tied to a perfectly prepared bowl of laghman alongside fresh naan bread.

The Holy grail of Uyghur gastronomy: laghman, plov and Kashgar barbecue. Photo: P.E.

Additionally, a longstanding passion of mine since first journeying the Silk Road in 1997—right after the Hong Kong handover—was to delve deeper into the mesmerizing Ancient Silk Road heritage of these oasis cities by retracing the path of the itinerant monk Xuanzang during the early Tang dynasty.

Thus, this updated Journey to the West offered a meaningful exploration of the Buddhist “Western Regions” before their integration into China.

Both Turfan and Kucha featured prominently in Xuanzang’s 7th-century pilgrimage. Accompanied by camels, horses, and guards, he traversed the Tian Shan mountains, encountered the Western Turks’ kaghan—who wore an elegant green silk robe and a three-meter silk banded turban—along the shores of deep blue Lake Issyk-kul (modern Kyrgyzstan), continuing all the way to Samarkand (present-day Uzbekistan).

This narrative serves as a compact jewel symbolizing the Silk Road’s allure, intertwining Chinese culture, Buddhism, the Sogdians (Persian traders pivotal to Silk Road commerce and key immigrant community in Tang China), and Persian civilization itself.

In Samarkand, Xuanzang experienced Persian culture’s richness for the first time, contrasting with China’s sophisticated traditions. Samarkand—not Rome—served as the major trade partner for the independent Gaochang kingdom in the 5th century and later for the Tang dynasty.

The remains of the Gaochang kingdom – outside of Turfan.

This brings us to intriguing geostrategic and geoeconomic facets of the Ancient Silk Road(s).

Few apart from leading scholars and economic strategists close to Xi Jinping realize the Tang dynasty itself was the main driver of the Silk Road economy during its height—from the 7th through 10th centuries. This chiefly involved funding the “Western Regions” in their military struggles against the Western Turks.

Consequently, Tang forces were stationed throughout the oases lining the Northern Silk Road. Interestingly, many soldiers were not ethnic Chinese but locals drawn from the Gansu corridor and the “Western Regions.”

The region witnessed frequent shifts in control. For example, the Tibetans briefly seized the pivotal oasis of Kucha between 670 and 692, prompting increased military spending on the Tang side. By 740, the dynasty annually dispatched around 900,000 bolts of silk to four military headquarters in the Western Regions: Hami, Turfan, Beiting, and Kucha—all prominent Silk Road hubs. This effectively supported the local economies.

Shifts in power continued into the early 9th century when Uyghurs began ruling Turfan. The Uyghur kaghan encountered a Sogdian teacher who introduced him to Manicheism—a Persian-founded religion (3rd century) teaching an eternal struggle between light and darkness for control of the cosmos.

The kaghan made a historic choice, officially adopting Manicheism, commemorated by a trilingual stone inscription written in Sogdian, Uyghur, and Chinese.

The long march from Buddhism to Autonomous Region

The Tibetan Empire remained powerful through the late 8th century, occupying Gansu in the 780s and capturing Turfan in 792. However, the Uyghurs reclaimed Turfan in 803. After a defeat in Mongolia by the Kyrgyz in 840, some Uyghurs migrated back to Turfan and established the Uyghur Kaghanate, with its capital at Gaochang City—a site I was fortunate to visit.

The ruins of Gaochang city. Photo: P.E.

From then on, Turfan was firmly Uyghur-speaking for commercial dealings, rather than Chinese. The economy predominantly involved barter, with cotton eventually supplanting silk as currency. Religiously, during the Tang era, Turfan’s population embraced Buddhists, Daoists, Zoroastrians, Christians, and Manicheans. Early 20th-century German archaeologists uncovered the remains of an Eastern Christian church (with Syriac liturgy) outside Gaochang’s eastern walls.

For a time, Manicheism served as the official religion of the Uyghur Kaghanate, accompanied by remarkable artwork. Yet today, only a single Manichean cave painting remains, preserved in the astonishing Bezeklik caves—a personal fee of 500 yuan granted me access, led by a deeply knowledgeable young Uyghur scholar.

The disappearance of Manichean murals coincides with the Kaghanate’s shift to Buddhism around the year 1000, abandoning Manicheism. Cave 38 in Bezeklik—the one I visited—displays this transition with layers: an older Manichean painting beneath a Buddhist one.

The political turmoil was relentless—a hallmark of Silk Road history. In 1209, the Mongols conquered the Uyghur Khaganate in Turfan but spared the Uyghurs themselves. By 1275, the Uyghurs allied with the legendary Kublai Khan. However, peasant uprisings toppled Pax Mongolica, ushering in the Ming dynasty during the 14th century. Notably, Turfan remained outside China’s core territory.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1383 when Xidir Khoja, a Muslim conqueror, seized Turfan, enforcing Islamic conversion that still influences the region to this day. Yet when locals in Xinjiang’s oasis towns are asked about their faith, many often avoid answering. The Buddhist heritage persists—etched in the collective memory and visible in Gaochang’s majestic ruins.

Xinjiang remained autonomous from China until 1756, when Qing dynasty forces annexed the region. During our recent travels, we found ourselves amid celebrations marking the 70th anniversary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, with red flags and “70” banners everywhere.

Urumqi: celebrating 70 years of Xinjiang. Photo: P.E.

This outlines the vision for the old “Western Regions”: an energy-abundant, ethnically diverse, multi-faith, strategically critical node on the New Silk Road within a “moderately prosperous” China.