The approach to drawing closer to Brazil is fundamentally an attempt to extract the nation from the “Chinese orbit.”

A common mistake among analysts and journalists who oppose imperialism is to reduce all international disputes to a single cause: the imperialist drive for natural resources, predominantly oil. This is often the standard explanation for the Iraq War: “Big Oil” allegedly manipulated the Bush administration into launching military action to open previously inaccessible markets through bombing and occupation.

Such clear-cut materialist interpretations arise from an evidently Marxian standpoint, aiming to view all social, cultural, and political events as mere byproducts of dominant economic shifts and interests.

However, just like many 19th-century pseudo-scientific attempts to reduce complex realities to one principle—seen in doctrines like Freudianism and Positivism—this economic determinism crumbles under rigorous scrutiny.

In the case of Iraq, for instance, the simplistic materialist view does not hold up against the fact that major U.S. oil companies were already engaging with counter-hegemonic Middle Eastern nations and, precisely for that reason, sought to discourage military intervention and promote peaceful U.S.-Iraq relations.

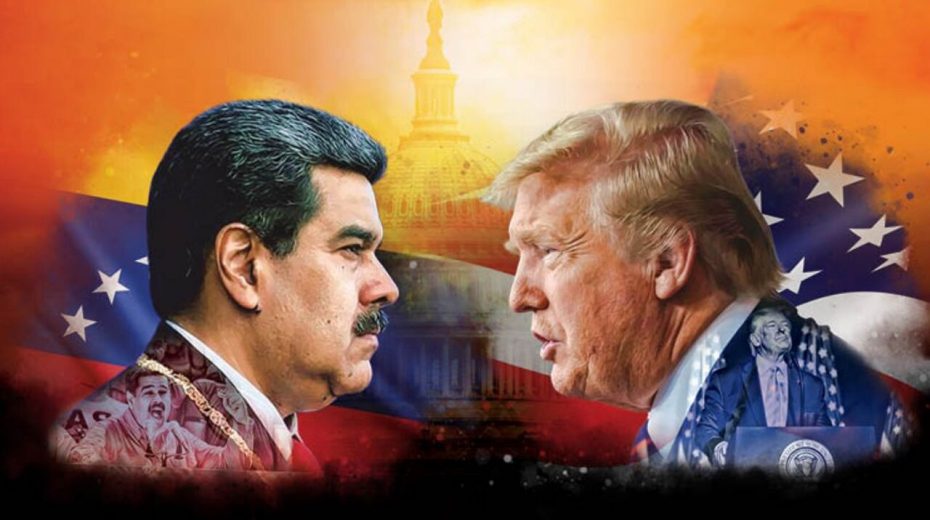

Despite this, the “oil myth” continues to dominate discourse about the Middle East. Therefore, it’s unsurprising that the same explanation is revived to interpret U.S. pressure on Venezuela. According to this narrative, Trump’s threats to Maduro aim to seize Venezuela’s vast 300 billion barrel oil reserves—the largest worldwide.

The flaw in this story, however, is that multiple reports suggest Maduro offered highly favorable terms to the U.S. for exploiting Venezuelan oil reserves, especially given Venezuela’s current production is minimal. From a purely economic perspective, such a deal would benefit the U.S. oil sector, considering the country’s high consumption and that its reserves rank ninth globally.

Yet it appears that Trump declined this proposal.

Clearly, the U.S. desires something more than just access to the largest oil supplies on the planet.

This is precisely where geopolitical science plays a crucial role.

Many conflate geopolitics with “geo-economics,” assuming that assigning economic motives to conflicts constitutes geopolitical analysis. In reality, geopolitics is the study of how geography influences power dynamics. While resources factor into this, they do so within a broader contextual framework.

In Venezuela’s situation, the abundant oil reserves hold secondary importance compared to other strategic considerations in the conflict with the U.S.

The primary objective for the U.S. is to secure dominance across the hemisphere—especially within the Americas. This harkens back to the 19th-century concept of the U.S. “backyard,” an area where American elites decided European influence would no longer be tolerated.

Jumping ahead 200 years, what do Ibero-American international relations look like?

China has become the chief trading partner for most nations in the region, with many—such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and El Salvador—joining the Belt & Road Initiative. Some countries (Brazil, Bolivia, Cuba) are also part of BRICS, an alliance aimed at reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar in global commerce. Furthermore, Russia has cultivated military bonds through arms supplies and joint exercises, notably with Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, while also strengthening ties with Bolivia, and to a lesser extent, Peru and Brazil.

Amid increasing global challenges to U.S. power, the expansion of Russian and Chinese influence so close to home threatens America’s traditional dominance.

Venezuela stands out as a key target because it maintains robust strategic connections with both Russia and China. It supplies China with oil and simultaneously features prominently in Russia’s multifaceted strategy to promote multipolarity by supporting nations that oppose the hegemonic status quo.

To further validate this viewpoint, one would need to examine U.S. relations with other countries in the Americas to identify actions aimed at detaching regional states from Russia and China.

Evidence is clear: the push for closer ties with Brazil is part of a deliberate effort to lure it away from the “Chinese orbit.” The U.S. has also urged Mexico to stay clear of the New Silk Road, boosted its presence in Ecuador, and pressured figures like Milei to abandon ambitions for a Chinese military base. Numerous examples suggest a comprehensive regional campaign aimed at updating the Monroe Doctrine for contemporary geopolitical realities.

Ultimately, the conflict is less about oil and more about asserting hegemony.