The NSS does not signify a departure from Empire; however, it concludes that maintaining dominance necessitates a ‘Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine’.

In his May address in Riyadh, President Trump outlined his transactional policy approach—pursuing peace through trade rather than conflict.

The language of the 4 December US National Security Strategy (NSS) advances this idea significantly: It frames global dynamics in terms of ‘regions of influence’ instead of outright hegemony and prioritizes managing financial interests of stakeholders. It abandons the concept of a rules-based order and does not invoke democracy or Western values.

Yet, what exactly does ‘peace through commerce’ entail?

The NSS reveals that Trump’s geopolitical vision centers on the threat of imperial collapse. It uses the image of Atlas holding up the world, emphasizing that the United States can no longer bear the empire’s burdens alone.

Ultimately, the document focuses on addressing the economic contradictions that have led the US into this predicament—soaring debt and unsustainable fiscal policies that, without correction, predict the fall of Empire.

A key question emerges: how can ‘Empire’ be financed amidst a deeply distorted economic landscape? The starting point acknowledges the failure of sanctions. Attempts to isolate China and Russia economically collapsed because those nations adapted, fortifying their economies internally and, in China’s case, strengthening their role in global supply chains.

Thus, a new imperial ‘model’ is apparent. The NSS indirectly indicates that without the dominance that compels major capital and infrastructure investments to flow into the US economy, combined with sustained dollar supremacy, America faces severe difficulties.

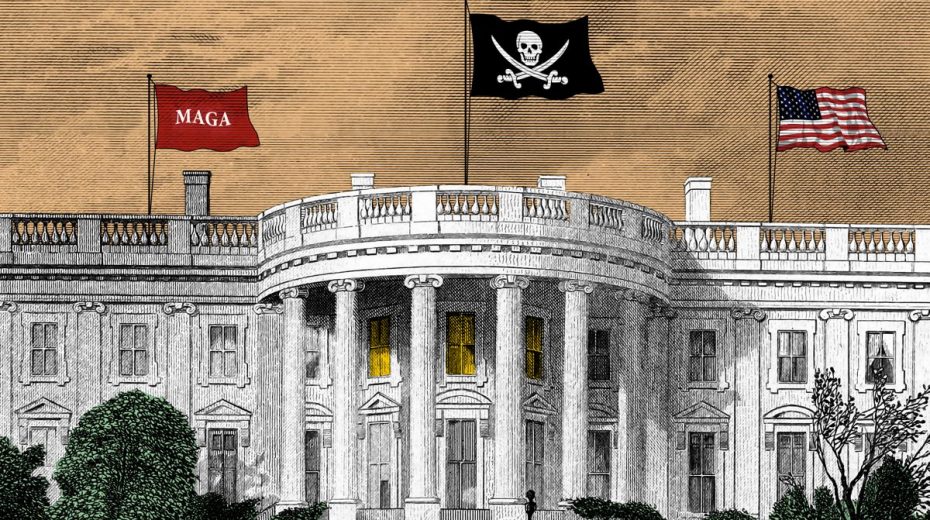

Therefore, the NSS does not represent a break from Empire; instead, it asserts that preserving a reduced form of American control requires what it terms a ‘Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine’.

The NSS introduction admits:

“American foreign policy elites, convinced that permanent American domination of the entire world was in the best interests of our country … [had] overestimated America’s ability to fund, simultaneously, a massive welfare regulatory-administrative state alongside a massive military, diplomatic, intelligence, and foreign aid complex.”

This places the financing of US foreign policy squarely in the spotlight.

Notably, regarding the funding gap, the strategy criticizes the free trade paradigm:

“They placed hugely misguided and destructive bets on globalism and so-called ‘free trade’, that hollowed out the very middle class and industrial base on which American economic and military pre-eminence depend.”

This critique arguably marks the most significant policy shift envisioned by the NSS, framing a choice between two economic models: the British free trade model championed by Adam Smith, and the ‘American System’ promoted by Alexander Hamilton. The document explicitly dismisses free trade and references Hamilton by name, signaling the aspirational path Trump follows.

The ‘American system’ was originally defined by the 19th-century German economist Friedrich List but came to be labeled ‘American’ due to its 150-year implementation in the US. This system used tariffs, government subsidies, and trade barriers to foster domestic industries and protect lucrative jobs. Post-WWII, the US shifted towards the British free trade approach. Trump has occasionally referenced Hamilton’s use of tariffs.

Yet, it must be stressed that transitioning to a closed economic model like those adopted by China (and to some extent Russia) to shield themselves from US financial aggression requires decades, and Trump is pressed for time.

The most apparent contradiction in Trump’s transactional approach lies in how to promote US debt sales to fund the budget when global demand for dollars is waning. This issue is compounded by Trump’s insistence on cutting debt service payments—threatening the sustainability of his high-profile ‘magnificent seven’ AI investments. Interest payments now consume 25 cents of every dollar raised by US taxes. This contradiction necessitates persuading investors to buy US debt, despite diminishing returns.

Trump’s strategy uses tariffs as leverage to extract substantial foreign investments by pressuring both allies and adversaries. Meanwhile, the US Treasury Secretary has urged global investors to purchase US debt. However, tariffs ultimately raise costs for American consumers and fuel inflation, worsening the economic challenges.

How does this transactional approach translate geopolitically? In Ukraine, it assumes that the prolonged conflict’s solution depends on maintaining opportunities for financial gain—that is, managing the division of the ‘Ukraine economic cake’ among stakeholders.

“Written in polite diplomatic terms, the continued payments are identified as ‘the prosperity agenda which aims to support Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction; the mooted joint US-Ukraine economic initiatives and the Ukraine recovery projects.’ (This is code speak for the US Senate and EU retaining a financial mechanism to exploit for personal benefit.” (i.e., a continuation of laundering pay-offs).

“From the language, it appears that Witkoff and Kushner are confident they can construct a financial reward system for western banks, investors, politicians and Ukraine officials that will retain the benefits of war without the ancillary ingredient of bloodshed.”

“If the U.S. delegation can pull this off, then Russia can gain the territory they want, corrupt Ukraine officials can keep skimming investment money, the EU can retain the power it wants to extract financial payments, American politicians can use the ‘long-term recovery projects’ for money laundering and quasi-public/private investment banks can benefit from the exploitation of Ukraine resources.”

This approach clearly draws on experience from negotiating New York real estate deals.

While financial interests indeed play a role in Ukraine, other stakes are involved: Russia aims to establish a solid, defensible security environment and defeat NATO and its European allies decisively. Conversely, European elites are equally determined to secure a crushing setback for Russia.

The NSS identifies European stability as a US priority. Yet, another influential US faction undermines this by pushing Europeans to rearm and prepare for war with Russia by 2027. European elites comply, unwilling to accept a Russian ‘victory’ and its significant influence in Europe. (Certain quarters in Brussels also harbor motivations of revenge.)

This highlights further evolution of the Trump business model, described by Alexander Christoforou as follows:

“Instead of trying to do everything yourself, you focus on core competencies as a business – right? And then you’re going to outsource everything else to partners. So, Europe will be outsourced to the Europeans. Asia will be outsourced to proxies in Asia … It’s like a franchise … we’re [the US is] going to focus on our neighbourhood [the western hemisphere] and then we’re going to have our three, four franchises out there and they’re going to pay us their 7% in franchise fees, but they’re going to take care of their region.”

The NSS clarifies:

“The terms of our agreements, especially with those countries that depend on us most and therefore over which we have the most leverage, must be sole-source contracts for our [US] companies. At the same time, we should make every effort to push out foreign companies that build infrastructure in the region.”

Regarding US emphasis on ‘regions of influence,’ a principal takeaway is the focus on the Western Hemisphere and Americas, with promises to “assert and enforce a ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine there.”

Here, a deeper zeitgeist emerges underpinning the NSS.

A move back to Hamiltonian economic principles is improbable under current conditions. Instead, US actions in Venezuela reflect a cold, if not potentially hot, competition over who will shape the forthcoming global order. Efforts to exclude China from Latin America are clearly underway.

Alex Kainer reports that:

“The Venezuelan government this summer offered Washington the most generous terms any adversary has extended to the US in decades. Venezuela proposed opening all existing oil and gold projects to American companies – granting preferential contracts to US businesses – thus potentially reversing the flow of Venezuelan oil exports from China back to the United States.”

“This wasn’t just a ‘deal’. Essentially, it was an unconditional surrender of resource sovereignty to American corporate interests.”

“The response from the Trump Administration: A hard ‘no’. Instead, [naval and] military assets continue to accumulate off Venezuela’s coast.”

“Here is where it gets really interesting. Whilst Washington rejected Maduro’s offer, Beijing doubled down. China unveiled a zero-tariff trade agreement at the Shanghai Expo in November – and a bilateral investment treaty. Private Chinese companies, CCRC, are now investing over a billion dollars in Venezuelan oil fields under 20-year production contracts.”

“So why would the US turn down exactly what it claims to want [Venezuela’s huge oil reserves], without firing a shot? The answer reveals something far more significant about how global power is likely to work in the future.”

“[Global power] will be about gaining control over the global economic architecture itself. And [the contest will revolve around] which system – Washington’s rules-based order or Beijing’s emerging alternative – will dominate in the Western Hemisphere and beyond.” Venezuela has become the chessboard where two incompatible visions of world order are clashing.

“What China has constructed in Venezuela is not just a trading relationship. It is an integrated supply chain of loans, ports, and commodity corridors – a network increasingly resilient to external pressure. That is precisely what frustrates Washington. Because when we discuss the emerging global order, we are considering the clash between an American-led system and China’s alternative.

“The American approach … relies on the dollar. It depends on financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank that operate under rules mostly written by Washington. It demands integration into a trading system where the US and its allies can impose sanctions on actors violating established norms.”

In contrast, China’s model requires none of these conditions: it does not insist on political reforms, adoption of the dollar system, or alignment with Washington’s foreign policy.

Why then did the US reject Maduro’s offer? Because the issue transcends oil, which is interchangeable. The critical factor is encapsulated in the NSS: Washington’s regional fortress, through Trump’s Monroe Corollary, pledges “that the US will make every effort to push out foreign companies that build infrastructure in the region.”

Through its naval blockade of Venezuela, Trump signals that Chinese supply chains, loans, alternative payment methods, and commodity corridors will be expelled from America’s Western Hemisphere fortress. Hence the naval presence off Venezuela and Cuba.

This marks the opening of the contest over who will define the new economic architecture and system in Latin America—and beyond.

This situation is highly symbolic and perilous. Whether enforced economically or militarily, the question remains: How will the Trump Corollary be upheld? Time will tell.