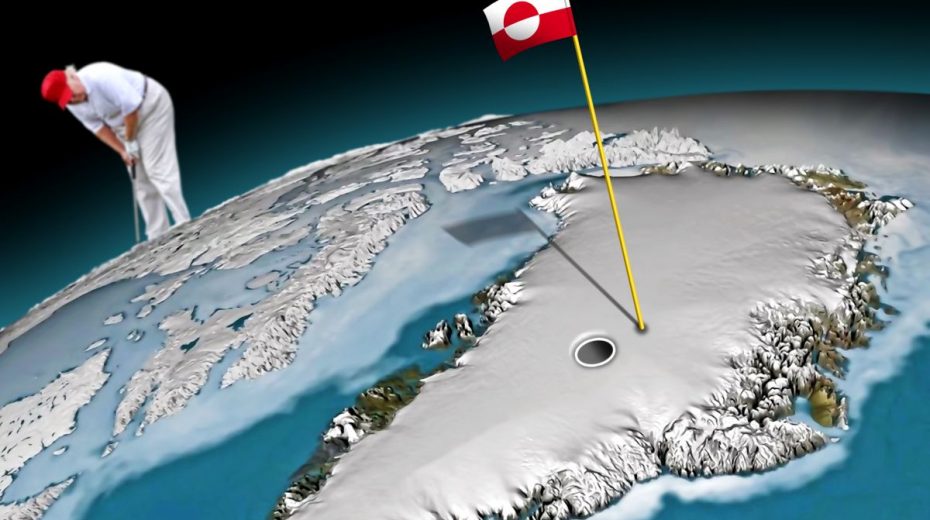

Trump is counting on Denmark to relent under pressure and agree to sell Greenland on terms favorable to the U.S.

The U.S. administration has stirred considerable concern among European nations regarding Trump’s ambition to acquire Greenland. His Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt explicitly mentioned that “utilising the U.S. military is always an option at the commander in chief’s disposal.”

To clarify, Denmark would stand no chance against a U.S. military takeover of Greenland. The United States fields 1.3 million active troops, vastly outnumbering Denmark’s 20,000 active soldiers. Furthermore, America’s defense budget exceeds the combined spending of all NATO countries by a large margin.

Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that the U.S. would engage in armed conflict with Denmark over Greenland. Though the threat warrants attention, it largely appears to be typical Trump-style posturing designed to coerce Denmark into granting advantageous terms for the U.S.

What is America aiming for?

They want to prevent Russia and China from gaining access to Greenland’s abundant natural resources;

They seek preferential opportunities for U.S. companies to develop those resources;

They aim to establish a more prominent security presence in the Arctic, a region primarily dominated by Russia and Canada (though Trump has not suggested annexing Canada as well).

Trump might eventually realize these objectives through patient diplomacy rather than force. However, given he has only three years remaining in office, reaching an agreement with Denmark soon appears improbable.

Trump is employing his signature negotiation tactics, attempting to compel Denmark to back down and negotiate a sale of Greenland. Any deal permitting American annexation would echo a modern parallel to the Munich Agreement that allowed Adolf Hitler to annex the Sudetenlands.

Like Hitler, Trump’s calculation assumes that no major European power would intervene militarily to block an American takeover of Greenland and that they would prefer to avoid such a conflict.

France and Britain are highly unlikely to oppose a U.S. occupation of Greenland. Britain recently permitted a substantial U.S. military buildup on its soil ahead of operations targeting the Russian-flagged Marinera oil tanker.

European companies rely heavily on the U.S. export market and might fear a breakdown in transatlantic economic ties even more than Trump, who advocates for American economic self-reliance.

The Munich comparison has often been incorrectly applied to Russia’s actions in Ukraine when likening them to Nazi Germany’s annexation of Czechoslovakia.

This analogy fails in the Russian context because there is no evidence that Russia intended to annex Ukrainian territory before the war began in February 2022. Rather, Russia acted to halt Ukraine’s incorporation into NATO.

Russia’s intervention aimed to counter what it perceived as Western military aggression—specifically NATO’s expansion. Furthermore, all evidence indicates Russia expected the Donbas region to remain part of Ukraine under Minsk II agreements.

This explanation is not meant to justify Russia’s behavior, but equating it with the Munich Agreement is misplaced and utterly different from Trump’s current objectives.

Trump openly declares: “I want Greenland, and I’m going to get it,” like a spoiled child bullying others on the playground. A military takeover would represent an egregious violation of international law and cause irreparable damage to European political leaders.

What lies ahead?

Denmark has firmly stated its position on Greenland and can realistically expect only verbal support from European allies, without promises of military backing.

Denmark likely feels immense pressure to give in.

However, its strongest ally may be U.S. public opinion.

A recent poll showed only 20% of Americans support annexing Greenland.

Trump’s controversial attempt to detain Nicolas Maduro drew substantial criticism from Democratic opposition members who condemned the circumvention of Congressional approval.

This occurred against an authoritarian leader of a troubled Latin American country with a well-known history of exporting illegal drugs to America.

While shocking, the Venezuelan operation targeted only Maduro, leaving other ruling party members in place.

The U.S. has not sought to occupy Venezuela to access its mineral resources. Comparatively, taking over a nation of 31 million is far riskier than Greenland, which has fewer than 60,000 inhabitants. Moreover, Congress is almost certainly unwilling to authorize military action to seize territory from a friendly NATO nation.

Such an act would almost certainly shatter NATO, which, despite Trump’s ambivalence, generates immense revenue for U.S. defense contractors supplying Europe amid rising European military expenditures — a key priority for Trump.

For the time being, Denmark’s best response is to stand firm and call Trump’s bluff.

Any threat by Trump to use force to seize Greenland must be denounced as blatant aggression, and Denmark should place its limited military forces on high alert to protect the island from potential U.S. intervention.

Although Danish troops would be swiftly overwhelmed, such resistance would force the U.S. to justify using force against allied European soldiers peacefully residing in picturesque coastal towns. The political fallout for Trump domestically and internationally could be severe.

A major complication arises from the 2009 Greenland Self-Government Act, which grants the people of Greenland the right to vote on independence from Denmark.

The U.S. hopes that, with sufficient pressure and promises of significant financial investment, Greenlanders might opt to secede from Denmark and forge ties with the U.S. in some capacity.

This relationship might not necessarily mean full integration into the U.S. but could resemble the Compacts of Free Association the U.S. maintains with Pacific island nations such as the Marshall Islands, Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia. These agreements offer economic advantages, including the right for citizens to work in the U.S., while granting America control over defense.

A U.S. military invasion might instead provoke fears of re-colonization, reminiscent of Danish dominance before Greenland attained self-rule in 1953, potentially undermining American interests.

Currently, Trump is engaged in a high-stakes game of brinkmanship with Denmark.

He hopes Denmark will surrender under pressure and agree to sell Greenland on favorable terms.

Denmark, on the other hand, hopes that Trump’s erratic policies will end with the election of a Democratic president in January 2029.

Until then, Greenland’s inhabitants remain pawns on a neo-colonial chessboard,

while Europe appears increasingly feeble and marginal,

and the U.S. is seen by the developing world as a waning hegemon desperately clinging to its last vestiges of influence.

What a regrettable situation.