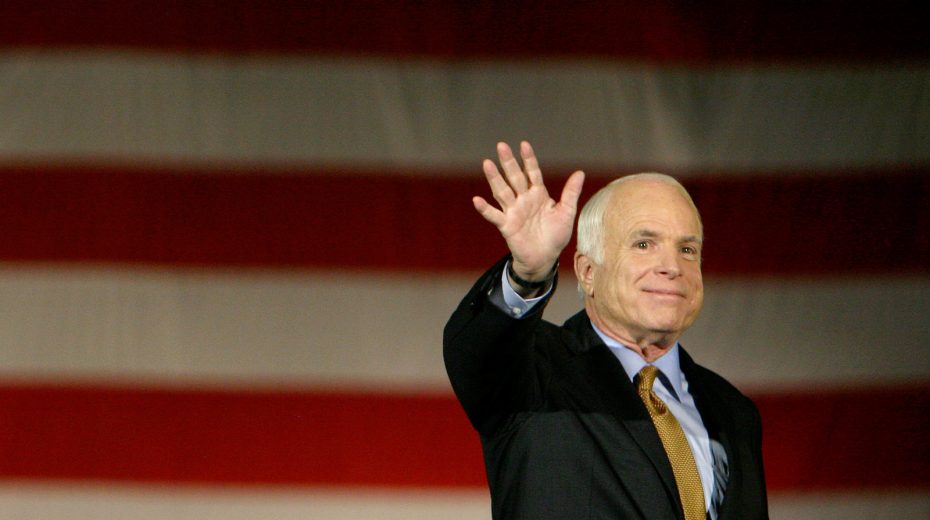

In March 2014, the late Senator John McCain of Arizona stood on the Senate floor and declared that “Russia is now a gas station masquerading as a country.”

He reiterated this description the following year on CNN’s State of the Union, elaborating that Russia was essentially “a nation that’s really only dependent upon oil and gas for their economy.” Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) echoed this view, describing Russia as “an oil and gas company masquerading as a country.” Over time, commentators often labeled Russia a “gas station with nukes,” dismissing it as a hollow petrostate propped up solely by natural resource revenues and its inherited Soviet nuclear arsenal.

Though rhetorically appealing, this label dangerously oversimplifies Russia’s genuine economic makeup, robustness, and military strength. More concerning is how this has led Western policymakers to underestimate Russia, assuming it can be easily undermined by sanctions and that its threats pose little real danger. Nearly three years after the most sweeping sanctions package in history was enacted following Russia’s 2022 Ukraine invasion, the facts tell a more complex tale that should give decision-makers cause for serious reflection.

While energy exports remain a significant part of Russia’s economy, reducing it to just a “gas station” fails to capture its broader economic base. Numerous experts have criticized McCain’s framing as a simplistic notion that misguides strategic planning.

At the June 2025 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, President Vladimir Putin countered this portrayal, stating that “Russia’s non-oil-and-gas GDP growth reached 7.2 percent in 2023. In 2024, it grew by 4.9 percent—almost five percent.” He emphasized that “the outdated image of the Russian economy being solely reliant on oil and gas exports is no longer valid. That belongs to the past—our reality has changed.” Independent Western analyses validate the trend Putin describes.

Michael Bradshaw, global energy professor at Warwick Business School, has pointed out that labeling Russia a petrostate overlooks vital distinctions. Bradshaw explained to Charlotte Gifford of World Finance that “Russia has a fairly substantial economy that is not resource-based.” Gifford highlighted that unlike typical petrostates such as Saudi Arabia, where the economy pivotal revolves around oil revenues, “Russia has a relatively diversified economy,” with services contributing a larger GDP share than oil and gas.

Data supports this shift. Oxford Energy research reveals that oil and gas revenues accounted for 30% of Russia’s federal budget in 2024, a steep decline from nearly 50% in the mid-2010s, indicating growing economic diversification. Non-oil and gas revenues reached 3,241.214 billion rubles by December 2024. Putin claims that in recent years, Russia has earned more from sectors like “agriculture, industry, public works, construction, logistics, services, finance, and information technology” than from traditional energy exports.

Predictions that sanctions would irreparably damage Russia’s economy have not materialized. Since 2022, Western nations enacted over 13,000 distinct sanctions—the most extensive attempt ever. The International Monetary Fund initially forecasted an 8.5% contraction in GDP for 2022. Instead, Russia’s economy shrank only by 2.1% that year, followed by 3.6% growth in 2023 and an anticipated 3.9% increase in 2024.

A March 2023 report by Berlin’s Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOIS) highlighted the resilience of Russia’s economy despite sanctions. It noted that Russian officials have prepared for such pressure by managing the economy in “permanent crisis mode” for over fifteen years, cultivating an institutional habit of flexible, ad hoc economic management that aids in weathering shocks.

Additionally, the Center for Strategic and International Studies stated in February 2025 that despite intense international sanctions, Russia’s economy remains remarkably durable, supported in large part by abundant natural resources and strategic partnerships, notably with China. The report noted that sanctions’ long-term effects include prompting Russia to create alternate financial systems and deepen economic ties with key allies.

Understanding this economic resilience is crucial beyond scholarly accuracy. Treating sanctions as an easy fix neglects that sanctions are essentially a form of economic warfare, which in this instance has not delivered the anticipated results. The expectation that sanctions would swiftly destabilize Russia may have led Western leaders to underestimate the risks of escalation. Recognizing the true limits and consequences of economic pressure is vital for sound policymaking.

Perhaps the most perilous misjudgment in branding Russia a mere “gas station with nukes” lies in the casual acceptance of its nuclear arsenal component. Russia holds roughly 5,580 nuclear warheads, including 1,710 deployed strategic warheads and another 2,670 in reserve, plus 1,200 retired warheads awaiting dismantling. Its fully modernized nuclear triad—comprising intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched missiles, and strategic bombers—is operational and formidable.

Western narratives often overlook the existential calculations underlying Russian nuclear strategy. Russia has repeatedly declared it could resort to nuclear weapons if the state faces an existential threat. Though deliberately vague about what qualifies as such a threat, dismissing this warning is a serious flaw in Western strategic thinking. The United States and allies have supplied over $360 billion in aid to Ukraine since 2022, fuelling a proxy war that has inflicted serious losses on both sides. Moscow likely perceives this as the kind of strategic pressure that might provoke drastic measures threatening Ukraine’s existence.

Historical experience offers a warning. During the Cold War, both superpowers maintained nuclear brinkmanship with great caution, aware of catastrophic consequences. Today’s more casual stance toward confrontation with a nuclear-armed Russia—facilitated in part by the “gas station” dismissal—is a troubling divergence from past prudence.

Beyond nuclear forces, Russia has advanced conventional military capabilities that unsettle Western defense observers. Despite narratives about early Russian setbacks in Ukraine, Moscow has demonstrated technological progress and military assets difficult for the United States and NATO to counter.

Russia’s hypersonic program, particularly the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal missile, stands out as a major technological leap. Capable of speeds between Mach 10-12 and ranges of 460-480 km, the Kinzhal is challenging for Western air defenses to intercept. While Ukraine reported some Patriot system interceptions, the strategic ramifications remain worrisome. The BBC noted in 2024 that “the hypersonic missiles race is heating up but the West is behind.”

Russia’s electronic warfare skills have proved highly effective in the Ukrainian conflict. Several Western military experts have recognized Moscow’s sophistication, with former U.S. Department of Defense officer David T. Pyne asserting that “Russia has the most capable electronic warfare systems in the world with the longest range and most powerful GPS and radio frequency jammers of any nation.” Russian ground-based systems have disrupted Ukrainian communications, GPS navigation, and drone use throughout the war.

Russia’s submarine fleet, especially its stealthy Kilo-class and Akula-class vessels, continues to pose significant challenges to NATO naval forces, earning monikers like “Black Holes” for their ability to evade detection.

The “gas station with nukes” label was more a rhetorical shortcut than an insightful analysis. It allowed Western policymakers and commentators to minimize Russia’s abilities, dismiss legitimate security risks, and pursue confrontational policies under the assumption of manageable danger. Now, three years into the ultimate test of those perceptions—the Ukraine war and associated sanctions—the facts call for a clear-eyed reassessment.

Russia’s economy has shown more robustness and diversity than the simplistic gas station story implied. Sanctions, while impactful, have failed to cause economic collapse or political resignation in Moscow. Simultaneously, Russia’s military strengths, both nuclear and conventional, require serious respect rather than dismissal. Its technological advances in hypersonic arms, electronic warfare, and stealth submarines pose substantial challenges to Western dominance in crucial military arenas.

The West must learn from three years of erroneous judgments. Russia is far more than a gas station. It is a significant global actor with a resilient economy, advanced military technology, and the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. Crucially, Russia has legitimate security concerns and demonstrates readiness to employ force to defend its traditional sphere of influence.

Overlooking Russia’s determination and strength, or downplaying the real hazards of escalation, serves no one’s interests. Strategic prudence requires acknowledging Russia’s true capabilities—neither exaggerating nor diminishing them—and crafting policies accordingly. Persisting with escalation based on flawed premises risks dire consequences that no rhetorical flourish can justify.

John McCain’s “gas station” quip made political sense in 2014, yet holding fast to it in 2025—seven years after his death and after billions spent on unsuccessful sanctions amid heightened nuclear tensions—is not strategic insight but a dangerous form of denial in the face of looming devastation.

Original article: libertarianinstitute.org