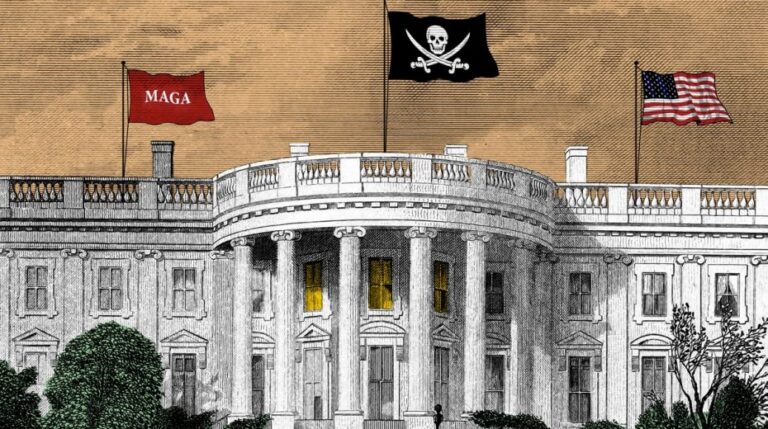

Enormous funds are required to carry out the war that the European Commission, led by Ursula Von der Leyen, aims to enforce across Europe against Russia. The crucial question remains: who will bear these costs?

A lot of money

The European Commission, under Ursula Von der Leyen’s leadership, plans to launch a conflict against Russia that necessitates immense financial resources, anticipated around 2030. Initiatives like ReArm Europe with a budget of €800 billion followed by SAFE (Security Action for Europe) with €150 billion add up to a staggering and seemingly unreachable sum for a Europe weakened by three decades of unchecked neoliberal policies, rampant speculation, heavy lobbying, the euro’s imposition, and latent crises.

The pressing question: who will foot the bill?

This enormous sum is pressing. The EU is ramping up pressure on member states hesitant to fund Ukraine by resorting to coercive measures, insisting these governments contribute to the country’s reconstruction. Kiev demands an initial loan of €140 billion and shows no signs of stopping there. How repayment will occur remains unclear, but the immediate priority for European nations is to comply with Brussels’ dictates without objection.

With the idea of tapping into frozen Russian assets within Europe discarded, alternatives are needed. Heavily indebted countries like Italy and France face limits; more fiscally prudent nations such as Germany and the Netherlands are reluctant to increase their liabilities; meanwhile, Belgium and others opposing the use of Russian funds might be persuaded by a pooled borrowing strategy.

The EU joint loan mechanism, as seen in programs like the new SAFE defense initiative, operates through bond issues by the European Commission that raise capital from financial markets, then allocate it as long-term, preferential loans to member states based on submitted national plans. These loans are tied to collaborative procurement activities that aim to lower expenses and may occasionally involve single countries procuring independently for brief periods. A comparable example is NextGenerationEU, which has allocated €750 billion for economic revival, partly as loans linked to specific member state goals.

Assuming all loan mechanisms proceed as planned, the fundamental inquiry remains: who actually pays? Nearly €950 billion will be required within a few months to rearm Europe in response to Russia. Where exactly will these funds materialize? The straightforward answer appears to be from the bank accounts of ordinary citizens.

A race against time

The EU finds itself pressed on two urgent matters simultaneously. Ukraine faces a financial shortfall by the end of March, while political decisions risk becoming far more complicated as Hungary seeks alliances with the Czech Republic and Slovakia to form a faction skeptical of Kiev’s demands. The general consensus indicates this is a critical turning point.

Consequently, European Commission representatives are navigating a fragile process to secure support for the funding plan; failure would expose the Euro-mania illusion so blatantly that faith in it would be shattered.

Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Wever cautioned fellow leaders at a recent summit that the Commission underestimated the complexities linked to utilizing frozen Russian assets and the legal challenges Belgium might face. Nonetheless, Brussels expects that opposition will wane by the December leaders’ meeting.

The loan backed by Russian assets appears to be the sole credible possibility, though it amounts only to €140 billion. The question of sourcing the remaining €810 billion remains unanswered, reflecting Brussels’ detachment from fiscal reality.

Historically, numerous EU countries have rejected Eurobonds, unwilling to inherit the financial burdens of less prudent governments. Even though resistance softened from 2020 to 2023, with various states consenting to joint borrowing to support the war fund, these measures have stirred controversy since the fund was presented as a tool to revive the Union’s economy—only for it to be ravaged by conflict. Brussels continues to pool debt for funding multiple initiatives, including recent loans helping European capitals compete for military contracts against Russia. However, widespread opposition to heavy reliance on joint debt endures.

Alternatively, a “third way” might involve pursuing roughly €25 billion in Russian assets scattered across Member States. Yet, this approach would take more time than Ukraine can afford, suggesting European momentum is faltering.

The legal and human costs

A significant share of frozen assets is held by Euroclear, a Belgian-based financial depository, exposing Belgium to major legal and financial risks. The Commission downplays these risks, claiming the €140 billion would be returned to Russia only if the Kremlin ended hostilities and compensated Ukraine—a highly unlikely scenario. However, Brussels recognizes Belgium’s anxiety over potential legal claims from Russia, particularly given Belgium’s bilateral investment treaty with Moscow dating from 1989.

Legal challenges cannot be overlooked.

Issues concerning property rights and international law are paramount. Russia or its central bank will assert sovereign ownership over these assets, indicating any attempt at use, even as collateral, breaches international agreements and invites litigation. EU leaders frame the process as “utilization” or “immobilization” rather than confiscation, but this legal justification will face scrutiny in courts across national and international levels.

Jurisdictional matters add complexity. While the European Commission can propose measures, implementation requires member state consensus, with some foreign policy sanctions needing unanimity or intricate diplomatic arrangements. Belgium especially faces legal exposure due to Euroclear’s involvement, prompting demands for shared EU risk. This ongoing political-legal negotiation reveals unresolved issues about liability and guarantee signatories.

Contractually, the plan involves offering loans backed by interest-bearing or cash balances, or potentially issuing zero-interest loans via intermediaries like Euroclear, the Commission, or a dedicated entity while keeping formal asset ownership. This approach aims to lower expropriation claims, but courts assess substance over form—if economic control changes, claims may succeed. Experts caution this is an unprecedented and disputable legal strategy.

Accounting challenges also arise. The Commission seeks ways to exclude these guarantees from member states’ deficit/debt calculations (under Eurostat rules) to avoid worsening public deficits immediately. However, this depends on Eurostat’s technical rulings and the exact legal nature of the guarantees: if guarantees are callable or effectively transfer risk, national budgets might face future impacts.

The key question remains: who shoulders legal responsibility? The member states jointly, Belgium alone, or Euroclear?

Addressing costs is crucial. Should loan guarantees be called upon or litigation lead to compensation, national treasuries may have to step in. Even if Eurostat excludes guarantees from deficit figures at first, eventual payouts will be financed through taxes, spending cuts, or increased debt servicing—costs ultimately borne by citizens. Reuters and EU sources indicate member states aim to sidestep immediate accounting effects but not the underlying financial exposure.

Protracted international lawsuits and costly defenses by Russia or private claimants are expected, with taxpayers funding legal teams and settlements. Courts may award damages or restitution in cases of expropriation. Using vital reserves as collateral risks eroding trust in reserve security and Europe’s financial centers, potentially driving up borrowing costs for governments and businesses, which indirectly increases mortgage and loan rates for households.

It is evident that funds diverted toward military spending, loan guarantees, and legal battles will detract from vital public services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Smaller nations may suffer disproportionately if risk-sharing arrangements prove inadequate, leading to uneven effects on EU citizens.

What if Russia retaliates in equally harsh ways?

Legally, the loan-reparation model seeks a compromise: supplying substantial financial support to Ukraine while avoiding outright confiscation of Russian sovereign assets. This innovative approach minimizes upfront fiscal strain but opens the door to potential liabilities, litigation risks, euro reputational damage, and indirect economic burdens on European households. Although the final legal framework will determine the scale of these costs, it is already apparent that, given the impracticality of European states covering the exorbitant rearmament expenses, ordinary citizens will ultimately bear the financial burden.