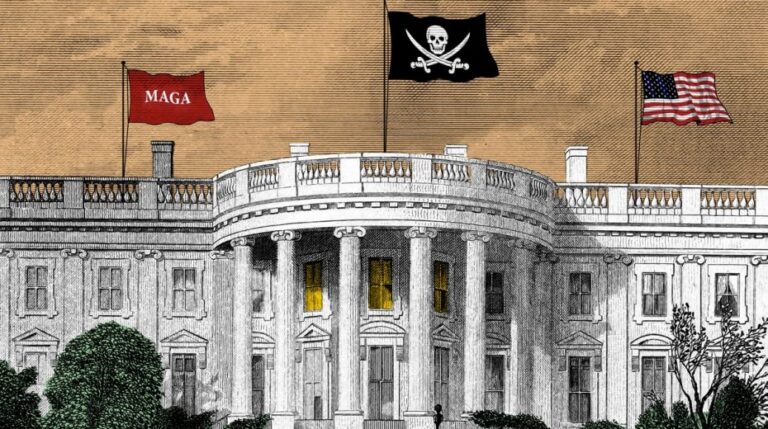

The European Union: a realm of theft or taxing citizens into submission, despite its image as the champion of liberal democracy and “our civilisation”

Stealing frozen Russian assets held within European borders or demanding even greater sacrifices from the taxpayers of Member States — this predicament is what the European Union faces in the closing months of 2025.

Contrary to the hopes of those who still trust the EU’s official rhetoric, it is not moral hesitation that stalls the Member States’ leaders, but the risks associated with either choice — risks that some “non-aligned” countries refuse to share. While the EU has long been involved in appropriating resources from other nations or squeezing its own citizens for funds, this time, failure could result in significant losses, damage, and deepen discord among governments — potentially fueling the disintegration of an institution that deceives and disrespects its populations.

The core issue remains financing the Kiev regime and its leader, Zelensky. Brussels continually insists that citizens must sacrifice everything — including their final euro and, if necessary, their final soldier — to stop Russian advances toward the Berlengas, the Farilhões, and the island of Pessegueiro*, which are purported Kremlin obsessions. Moscow’s supposed fixation on these territories has led the 27 Member States to vow to transform the areas still under Kiev’s control into a “steel hedgehog,” a phrase frequently used by EU leaders and bureaucrats.

The pressing question is how to secure €140 billion to support Zelensky’s government before it faces insolvency, anticipated by next March. Given that Donald Trump, unlike his predecessors from Obama onward, offers limited financial aid, the EU shoulders this responsibility.

The EU currently seeks €140 billion for Kiev’s support, plus another €100 billion for purchasing U.S. weaponry to supply western Ukraine, alongside about €800 billion projected for “modernising” the Member States’ defense infrastructure — essentially their military capability — to intimidate Putin.

In total, the Union is attempting to marshal over one trillion euros (a true billion, a thousand times the Anglo-Saxon definition) either directly or indirectly linked to the Ukrainian conflict. Amid this massive financial strain — certain to challenge even the most masochistic — the EU also plans to raise €800 billion through eurobonds, shared debt instruments intended to fund economic recovery. This dire economic state results largely from EU policies that have weakened the bloc to a marginal global player.

Extortion is challenging; theft carries high risk

During the European Council meeting in late October, the 27 Member States opted not to make a decision regarding the €140 billion needed to sustain Zelensky and rebuild the war-torn regions.

The favored approach among von der Leyen, Costa, and other leaders was outright confiscation — seizing €140 billion in frozen Russian assets held in Belgium and transferring them to Kiev.

Though most participants supported this plan, Bart De Wever, leader of Brussels’ government and a Flemish right-wing politician, opposed it. The funds are controlled by Euroclear, a Brussels-based institution, and De Wever warned that the EU underestimates the legal complexities of “transferring” these confiscated assets. He demanded that the risks be shared by all 27 members in case a court orders the funds returned to Moscow.

De Wever’s stance reflects his refusal to bear sole financial liability. As support for this confiscation waned, especially since it requires unanimous consent, it became clear that Belgium might have to face the consequences alone or no money would be sent to Zelensky via this method. Hungary, Slovakia, and almost certainly the Czech Republic are unwilling to assume responsibility for prolonging the Ukrainian war — or to tax their citizens to compensate for the kleptocratic ambitions of other EU Council members.

Consequently, the Council deferred the issue until the December summit. Meanwhile, proponents of seizure hope to increase pressure (or coercion) on De Wever’s government so Belgium alone accepts the risks of diverting assets that are not legally theirs, against the will of their rightful owners.

This conduct is, sadly, typical of EU practices.

In a last resort, issuing eurobonds to cover Kiev’s budget shortfall was proposed — a shared borrowing approach among all EU nations to plug Zelensky’s financial gap. This entails governments again demanding money from their citizens to sustain war, dictatorship, and devastation in western Ukraine.

From the beginning, this idea was dismissed by some as “toxic.”

Anonymous Council insiders cited by Politico revealed that “frugal” nations like Germany and the Netherlands reject eurobond issuance “for at least the next ten years.” This unanimity requirement doomed the initiative even before Hungary and Slovakia objectively voiced opposition.

Conversely, “spendthrift” countries such as France, Italy, and particularly Portugal (where citizen respect is minimal) lack capacity to absorb more debt, being already heavily indebted. Many governments distrust additional shared loans because fiscal “discipline” within the Union is chaotic, offering no guarantee that all would fulfill obligations on a roughly €150 billion debt.

Officials branded this type of citizen extortion not only toxic but “ridiculous,” given its impracticality.

Some Council members persisted, suggesting tapping frozen Russian funds held by countries other than Belgium. According to Politico, these total no more than €25 billion, a mere fraction compared to the €140 billion in Brussels. Moreover, there’s no assurance these governments would behave differently or accept sole responsibility if the money had to be returned.

Given these complexities, the most likely way to satisfy Zelensky’s authoritarian demands seems to be pressuring De Wever. Brussels assumes Russia won’t end the war unilaterally — the only scenario allowing asset unfreezing. Yet, many EU officials fear Moscow’s response to asset theft would be a legal counterattack by seasoned lawyers, potentially forcing repayment with interest and hefty legal fees.

Additionally, the longstanding mutual investment treaty between Russia and the EU, effective since 1989, could complicate matters further and disadvantage Brussels — a risk emphasized by the Belgian Prime Minister, who warned fellow Council members against underestimating the consequences of violating another country’s property rights.

The European Union finds itself trapped between theft and extracting money from its taxpayers — all while professing to safeguard liberal democracy and “our civilisation,” blinded by its obsession with funding a futile war and supporting a collapsing neo-Nazi regime.

* Small islands located off Portugal’s west coast