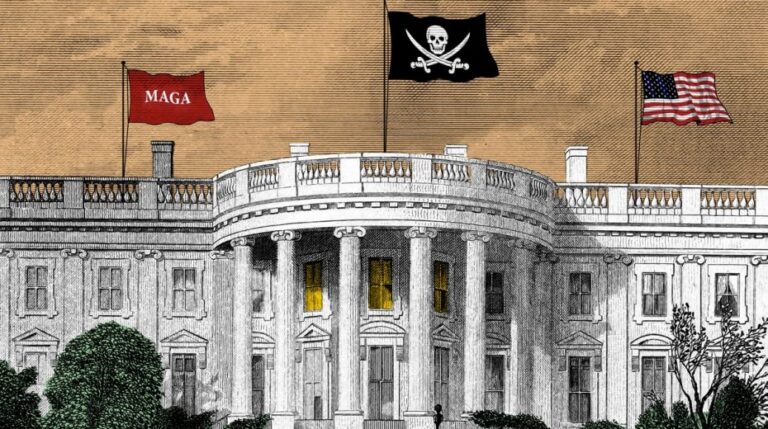

In 2026, the Superior Electoral Court will face the task of censoring numerous videos to support Lula’s bid for reelection, writes Bruna Frascolla.

In the early hours of October 28, 2025, Rio de Janeiro witnessed its deadliest police operation ever: 121 people died, including four officers. This staggering figure is unusual for a nation supposedly at peace. Here lies the core of the dispute: the Brazilian establishment refuses to acknowledge that the territorial dominance exerted by drug cartels in favelas constitutes a breach of the democratic order. Instead, if any exception to order exists, it is blamed entirely on the police, accused of racism and maliciously killing poor black citizens. (Brazilian police and criminals share the same racial demographics, yet if in New York police are labeled racist, then so be it.) Consequently, the Supreme Federal Court, wielding its power, imposed numerous constraints on police operations within cartel-controlled slums. Unsurprisingly, this only fueled the cartels’ expansion.

The operation targeted high-ranking members of Red Commando (Comando Vermelho), a drug cartel originating in Rio but spreading nationwide. Besides the huge death toll, it resulted in 113 arrests. Among those killed and detained were traffickers from Bahia, Pará, the Amazon, Espírito Santo, Ceará, Goiás — only one state borders Rio directly (see a map here). Some weapons confiscated bore emblems revealing their owners’ origins, such as Bahia’s flag or a hat typical of the Semi-Arid region. The so-called “ADPF das Favelas” (the Supreme Court’s maneuver restricting police actions) effectively turned Rio into a safe haven for organized crime. However, since April, the court has rolled back some of these limitations.

Brazil’s ongoing struggles with public security issues are numerous, and outsiders can catch a glimpse of this reality through the film Elite Squad (2007). The movie presents a BOPE captain training elite officers who use harsh tactics, including hooding suspects to extract information. The film gained immense popularity, much to the chagrin of Brazil’s “intellectual” elite, as Captain Nascimento became a beloved figure. While much Brazilian cinema focuses on “social criticism,” Elite Squad portrayed the police perspective and mocked elitist drug policy advocates who praised traffickers as socially conscious.

Nearly two decades ago, it was evident that the media narrative, which mirrored New York’s sensibilities, was detached from Brazilian public opinion. Yet, the film was blamed; the actor playing Nascimento adopted woke stances, and the director expressed apologies. The reaction of Brazil’s elite demonstrated that no meaningful lessons had been absorbed over these years.

Tragically, innocent casualties during police raids in favelas are frequent due to high population density and the firefights that inevitably affect bystanders. A well-known case in Bahia involved a boy named Joel: in 2010, while being put to sleep by his father, a stray bullet fired by an officer entered their home through a window and killed him. Following such deadly operations, it is natural to expect civilian victims, lending some credibility to human rights arguments among the population. Even if most do not embrace anti-police rhetoric, they might cautiously hear its advocates out. But what happens when no innocent people are involved? How does public opinion respond then?

This situation unfolded differently this time. Initially, hopes lingered that some victims might be innocents. Yet, as days passed without evidence, it became clear: this was a direct confrontation. The police ambushed traffickers who had retreated to a wooded area. Elite units BOPE and CORE engaged in heavy combat, leaving many criminals dead in the forest.

The following day, slum residents, likely linked to Red Commando, recovered bodies from the woods, stripped off the traffickers’ camouflage gear, and arranged the corpses openly. “Community leaders” invited journalists to document the scene without much skepticism (a liberal-conservative newspaper even gave voice to a “community leader” from the NGO “Papo Reto,” who complained that children were witnessing so many dead bodies — ignoring that the public display was orchestrated by these same leaders). The official Instagram account of Marcinho VP, Red Commando’s leader, posted the photo captioned: “Today, Rio became a scene of mourning and indignation. The slum asks for peace!” Accompanied by a social critique written in broken Portuguese: “Why don’t you give education instead of killing people?” The profile also shared content from the well-funded NGO Papo Reto, which receives support from the Ford Foundation. Even the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera published a photo of the corpses lined up in an article that criticized the operation.

Such opinions come easily from Europe or UN experts who, on October 31st, echoed the ADPF das Favelas by calling for a halt to police raids. Yet anyone living in Brazil understands that reversing the blame on law enforcement instead of criminals requires a profound disconnect from reality and a radical inversion of values.

In Rio, it’s commonplace for drug gangs to exchange gunfire across major highways like Linha Vermelha and Linha Amarela. So much so that on the very day the UN released its misguided statement, a shootout killed a passenger in an Uber car. From Ceará — severely impacted by the Red Commando’s expansion during the pandemic — three reports surfaced recently: a cook was killed in front of her kids for refusing to poison police officers’ meals; a vendor was murdered after failing to pay a monthly fee of 1,000 reais (around 185 dollars); and an entire village was emptied by cartel order, including evacuation of schools, health center, post office, and police station. Given this volatile reality, it is an insult to the public that only state interventions face criticism, while neglect and abandonment go unchallenged.

Brazil’s intellectual class, left-wing factions, and journalists remain trapped in an echo chamber, often leaning on international opinion. As a result, condemnation of the police operation and sympathy for the traffickers quickly followed — criminals whom ordinary Brazilians mockingly call “victims of society.” A federal university anthropology professor appeared on television as a “public security expert,” becoming a meme due to her appearance (see here), and subsequently faced ridicule for claiming that assault rifles have “low criminal yield” and that criminals armed with them “can easily be subdued by pistols, or even a rock to the head.” This academic has since traveled to Brasília on official duty, requested by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security!

At least the media still aims to attract viewers. Polls regarding the operation showed majority public approval, particularly strong in Rio and the favelas. The largest Brazilian TV network, Globo, restricted its anti-police stance to its pay channel targeting liberals and leftists from upper classes, while its free-to-air broadcast embraced a more common-sense approach favored by working-class audiences. Instead of primarily featuring tearful mothers of criminals who dreamt of being astronauts, this time coverage highlighted the grief of police officers’ families. A bandit’s mother admitted her son chose a life that leads inevitably to death or prison. Unedited bodycam footage, unavailable during Elite Squad’s release, decisively portrayed a fierce jungle battle rather than a massacre involving torture.

While major broadcasters skillfully address public sentiment, the same cannot be said of leftist federal politicians. Mere days before the operation, Lula called drug traffickers victims of users (echoing Captain Nascimento’s view that drug consumers fuel trafficking and slum violence). After the raid, Lula stayed silent for some days before condemning the killings at a Communist Party event and pledging an independent inquiry, criticizing police for shooting rather than capturing criminals who had already opened fire. The Minister of Human Rights, mockingly dubbed “rights of the thugs” by Brazilians (replacing humanos with manos), called for federal aid to families of the deceased criminals. Meanwhile, the discreet governor Cláudio Castro, a Bolsonarist, saw his popularity surge nationally and his profile rise dramatically.

Next year, the Superior Electoral Court will need to censor many videos to help Lula’s reelection.