If a government opposing Lula’s Party had enacted the Anti-Terrorism Law, it might have been more effective.

Brazil’s anti-terrorism legislation is frankly absurd. Article two defines terrorism as “the practice by one or more individuals of the acts provided for in this article, for reasons of xenophobia, discrimination or prejudice based on race, color, ethnicity and religion, when committed with the purpose of provoking social or generalized terror, exposing people, property, public peace or public safety to danger.” (Emphasis added.) This means that if a group threatens to deploy explosives, “violently seizes […] schools, sports stadiums, public facilities or places where essential public services operate” or “attacks [someone’s] life”, but does so under slogans of love and world peace, it is not categorized as terrorism. Terrorism applies only when actions are motivated by xenophobia, etc. (This “etc.” may even extend to transphobia, given the Supreme Court’s ruling equating it with racism.) Consequently, few would argue the law is anything but foolish.

How did such a flawed law come into being? The answer is partly found in the president’s name at its 2016 signing: Dilma Rousseff, a former guerrilla fighter—or, using military terms, a former terrorist.

During the Cold War, the CIA backed military coups across South America. Decades later, Jimmy Carter promoted the U.S. as a defender of Human Rights (mockingly called Dudes’ Rights by Brazilians, replacing humanos with manos) and pushed for political liberalization and the fall of dictatorships. Brazil was no exception. Notably, the media sectors that supported the 1964 coup defending “democracy” later championed the “end of dictatorship” and “democratic opening.” The media glorified a youthful, socially conscious artistic class poised to overthrow the regime—the so-called festive left.

Alongside this festive left, a militant left also operated in the Americas, relying on terrorism to topple non-communist governments. In Brazil, the first terrorist act came from a Catholic group: in 1968, Ação Popular (AP) planted a bomb at an airport targeting future president Costa e Silva. Though the Guararapes Airport Attack was unsuccessful, it caused fatalities. Broadly speaking, various ideologies fueled this movement: Foquism, inspired by Che Guevara and theorized by Régis Debray in Revolution in the Revolution (1967); Maoist guerrilla activity in the Amazon (Guerrilha do Araguaia); and Carlos Marighella’s 1969 Minimanual for the urban guerrilla, which openly glorifies terrorism: “Today, to be ‘violent’ or a ‘terrorist’ is a quality that ennobles any honorable person, because it is an act worthy of a revolutionary engaged in armed struggle against the shameful military dictatorship and its atrocities.”

The Brazilian left continues to equate the “fight against dictatorship” with anti-colonial resistance. However, Brazil’s military regime, developmentalist and not automatically aligned with the U.S., retained broad support during the 1970s. The economy boomed, and public security issues were manageable—the closest historical precedent to today’s cartels and militias is Cangaço, which ended in the Estado Novo when the government eliminated the bandits and displayed their heads at the Institute of Legal Medicine. The armed resistance mainly comprised discontented middle-class university students willing to use violence against a regime popular with most citizens, yet claiming to represent the people’s true will.

Dilma Rousseff fits this profile as a former member of COLINA and VAR-Palmares, groups known for bank robberies, “expropriations,” bombings, and kidnappings of officials. Naturally, the military government sought to crush such groups, employing CIA-assisted torture tactics. Importantly, during this time, guerrillas and criminals were imprisoned together, leading to the formation in 1979 of the Red Phalanx, or Red Command, Rio de Janeiro’s most notorious faction, born from middle-class communists mingling with slum drug dealers.

While Jimmy Carter’s U.S. administration (1977-1981) publicly advocated Human Rights, in Brazil, denouncing torture and championing democracy became a fashionable cause for the “beautiful people” and the festive left. The military government was not a dictatorship but rather a hyper-regulated formal democracy, featuring separation of powers, presidential transitions, and direct elections for many offices. This formal democracy enabled the coup that ousted the “communist” leader elected by the populace. Crucially, the Brazilian debate polarized regimes into binary categories: if good, democratic; if bad, dictatorial. Tertium non datur.

In this narrative, all Marxist guerrillas seeking to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat should have been condemned. Yet, the media and academia canonized anyone “fighting against dictatorship,” including communists. Some guerrilla leaders, like Fernando Gabeira, later joined the festive left. As Soviet communism declined, Brazilian communists shifted toward New York liberalism, focusing on ecology, drug policy, and Human Rights. Those retaining orthodox communist ties dismissed liberal democracy as false democracy, avoiding direct references to the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and instead espousing “popular democracy,” as seen in North Korea’s official title.

Thus, the New Republic officially started in 1985 with the first civilian president’s inauguration, but practically began in 1988 with the new Constitution, crafted by law graduates eager to advance human rights. One consequence previously discussed is the near-absolute power wielded by the Public Attorney’s Office and the Supreme Court. This framework traces back to the 1979 Amnesty Law, shaped under Human Rights pressure, which freed both left-wing terrorists and right-wing torturers.

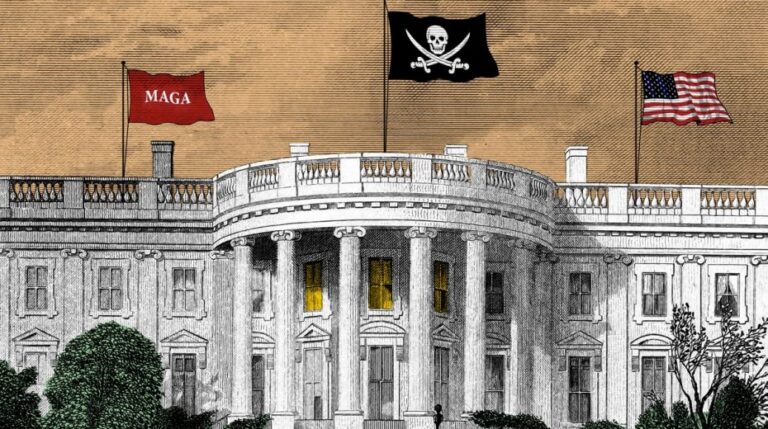

If the Anti-Terrorism Law had originated under a government opposed to the PT (Lula’s Party), it might have been more robust. Conversely, under a Lula administration, it could have been designed to shield groups like the MST and MTST. A Dilma presidency was arguably the worst possible context, as she pushed to politicize the military era deeply, amid significant calls to revisit the Amnesty Law and hold torturers accountable.

Was there a conspiracy to time the law’s creation during Dilma’s tenure? That would be wishful thinking. The push for anti-terrorism legislation emerged due to Brazil hosting the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Staging such events demanded appropriate anti-terrorism measures. In the run-up to the World Cup, left-wing factions predicted the event would be disrupted, with black bloc activists vandalizing public spaces and even killing a journalist. Rousseff had the strongest incentive to pass anti-terrorism laws, yet the version she enacted ended up shielding these offenders. For her, political terrorism was seen as justifiable, and the law’s language punishes only less honorable objectives.

Due to a delusional and morally misguided glorification of the “struggle against dictatorship,” the Brazilian left remains remarkably irrational on some of the most critical issues.