The thirtieth United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) kicked off this week in Belém, a key city within the Brazilian Amazon. This summit stands as the premier global platform for discussions and advocacy centered on the Green Agenda and climate issues. Hosting the event at the so-called “gateway” to the Amazon carries clear symbolic weight. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva promotes COP30 not only as this year’s most decisive event but as the most pivotal climate summit ever, dubbing it the unavoidable “moment of truth” for humanity.

Lula’s opening remarks struck an alarmist tone close to apocalyptic, illustrating a bleak scenario filled with threats of severe droughts, rising sea levels flooding coastlines, mass displacements, and biodiversity loss. He even highlighted a recent tornado in southern Brazil as evidence, warning that only urgent and forceful measures can prevent such disasters.

Yet, the call for “drastic and immediate actions” confronts a major hurdle in today’s widespread viewpoint that climate initiatives might exacerbate inequality rather than alleviate it. Proposals like heavier taxation on private cars, restrictions on meat consumption, and progressive elimination of fossil fuels paint a future in which working-class people may lose access to cars, meat, travel, and face rising costs. Meanwhile, wealthier elites would still afford multiple cars, luxurious meats, private jets, and unrestricted consumption—simply at a higher price point.

It is somewhat ironic to note the hundreds of heavily polluting private jets flying into a climate summit—where their passengers then call for a ban on cars. One private jet alone generates pollution equivalent to 200 automobiles annually.

Contrary to Lula’s suggestion, this moment does not appear to represent a historic turning point. Should this be the case, it would indicate that the Brazilian President’s strategic forecast for 2025 is miscalculated.

Problems begin with Lula’s administration choosing to reschedule the BRICS Summit calendar to prioritize COP30. The BRICS alliance is central to the shift towards a multipolar global order. Traditionally held at year-end, the 2025 BRICS Summit was unexpectedly brought forward to mid-year by Brazil as chair. This move condensed the diplomatic timeline and undercut the chance to follow up on key achievements from the 2024 Kazan Summit in Russia, which addressed vital matters like developing financial frameworks independent of the US dollar and managing political coordination in regional conflicts.

This shift is far from a simple scheduling change. It plainly reveals the priorities of Brazil’s Foreign Ministry (Itamaraty), placing the Green Agenda clearly ahead of the Multipolar Agenda. Whereas the latter aims to reshape global power by diluting the dominance of the G7 and U.S. unipolarity, Lula treats the Green Agenda as a more prestigious platform with greater international legitimacy. It connects Brazil to “democratic” nations within the “International Community,” distancing it from “autocracies,” which Lula regards with increasing mistrust.

However, this focus may backfire. Prioritizing an event centered on decarbonization over a forum comprising some of the world’s fastest expanding economies—many reliant on fossil fuels—risks diminishing Brazil’s influential role within this emerging coalition.

The notion that Lula may be placing undue emphasis on COP30 becomes clearer when considering the dramatic shifts affecting the Green Agenda’s main backers. Over the past decade, the United States and the European Union drove climate ambitions forward, but now this momentum faces serious setbacks.

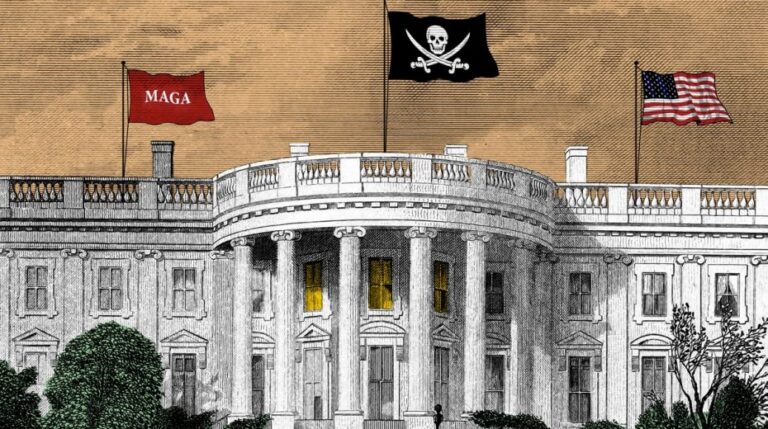

In the U.S., the election of Donald Trump in November 2024 upended international climate policy. Staying true to his campaign pledges, Trump recommitted to energy independence at all costs, aggressively dismantling the “green” legacy of his predecessor. Government funding for renewable energy and climate adaptation programs was slashed; a vast expansion of oil and gas drilling licenses — including fracking — occurred; and support from USAID to environmental NGOs abroad essentially ended. The lack of any senior U.S. delegation in Belém does not signal a boycott but rather reflects a deliberate policy shift: climate issues no longer hold national security priority in Washington and are effectively ignored.

Meanwhile, Europe’s green initiatives face harsh geopolitical and economic obstacles. Sanctions against Russia following the Ukraine conflict precipitated a cascade of challenges. The disruption of cheap Russian gas supplies, compounded by the Nord Stream pipeline attacks, plunged the continent into a prolonged energy emergency. Without quick alternatives, nations like Germany had to restart coal-fired plants, a highly polluting energy source. At the same time, rural protests—ranging from Dutch farmers to Polish truckers opposing stringent environmental regulations—pushed governments to ease their decarbonization goals. The “European Green Deal” remains official policy but its enactment has been diluted by pragmatism and concessions.

Throughout this year, measures like postponing the anti-deforestation legislation until next year, granting carmakers a two-year extension on pollution standards, and deferring 2030 climate targets to 2050 demonstrate the EU’s softening stance.

One clear outcome of these global changes is COP30’s striking lack of political weight. The number of attending heads of state is noticeably smaller than in past conferences. This decline follows a trend already apparent at COP29 compared to COP28, signaling waning global engagement with the Green Agenda.

As noted, the United States is fully absent from the summit. Major emerging powers such as China and India have dispatched only deputy ministers or ambassadors, indicating low-level participation. Many countries in the Global South have followed a similar approach or sent no prominent representatives at all.

This trend reflects shifting global priorities. Amid rapid geopolitical change, mounting regional conflicts like those in Ukraine, the Sahel, Taiwan, and Palestine, and the rise of alternate power centers, climate issues are increasingly sidelined. For nations grappling with pressures on sovereignty and economic growth, it is risky to sacrifice industrial strength and state power in favor of an abstract environmental cause—especially when historically largest emitters seem to be retracting their commitments.

Furthermore, COP30 continues to overlook nuclear energy, which many experts regard as essential for a realistic energy transition. Civil nuclear power uniquely provides stable, reliable baseload electricity without greenhouse gas emissions. Countries like France, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates exemplify its effectiveness.

Russia’s ROSATOM supports the energy shift by partnering with nations in Africa, Western Asia, and Latin America to build nuclear reactors.

Advancements such as Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) offer safer, more cost-effective, and flexible nuclear options. Yet, within the prevailing COP ideological framework, nuclear power remains taboo, often conflated with fossil fuels, while intermittents with uncertain grid reliability receive sole attention and funding.

Hence, COP30 in Belém unfolds amid notable contradictions: grand rhetoric contrasts with scant political presence; a declared “moment of truth” for climate action coincides with the absence or reduced involvement of key players; calls for radical change ignore one of the most potent energy technologies available.

By placing excessive expectations on this single event, Brazil risks squandering valuable political influence and fueling the growing weariness and doubt that surround international climate talks.