As 2025 ends, it is necessary to assess the state of the European economy. Unfortunately, the findings are not encouraging.

Eurostat has so far released data on the gross domestic product and its elements up to the third quarter of 2025. When averaging these three quarters, the EU’s GDP growth reached only 1.48% compared to the same period in 2024. The euro zone performed even more poorly, with growth at 1.35%.

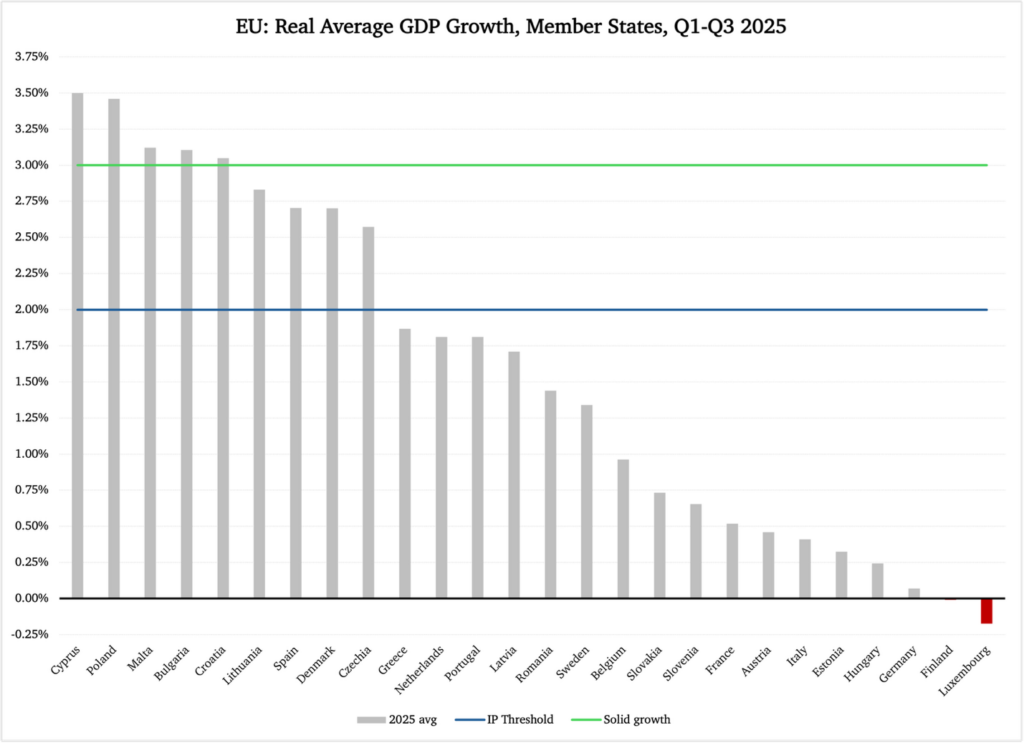

There is no sugarcoating these figures—they are quite disappointing. Examining individual EU member states reveals an even more bleak outlook: among the 26 countries shown in Figure 1 (excluding Ireland due to the volatility caused by foreign direct investment), a mere five exceed the solid-growth benchmark of 3%. Only nine nations surpass the crucial 2% threshold:

Figure 1

An economy unable to maintain real GDP growth above 2% over the long run typically faces gradual declines in living standards. Such economies often exhibit signs of structural stagnation or industrial poverty, characterized by youth unemployment rates exceeding 20%, private consumption making up less than half of GDP, and government spending combined with taxes accounting for over 40% of GDP.

While a full analysis of poor-performing EU economies through these structural poverty indicators is beyond the scope here, it is likely that countries with GDP growth under 2% also suffer from these long-term stagnation symptoms and declining living conditions.

It’s important to note that Figure 1 shows 11 nations with real GDP growth below 1%, among them Europe’s two largest economies: France and Germany.

To highlight the gravity of the European economic situation, as I recently outlined, the short-term forecast offers little hope. The euro zone’s total GDP growth is projected to hover at about 1.4% through 2027, with the EU as a whole expected to mirror this sluggish performance.

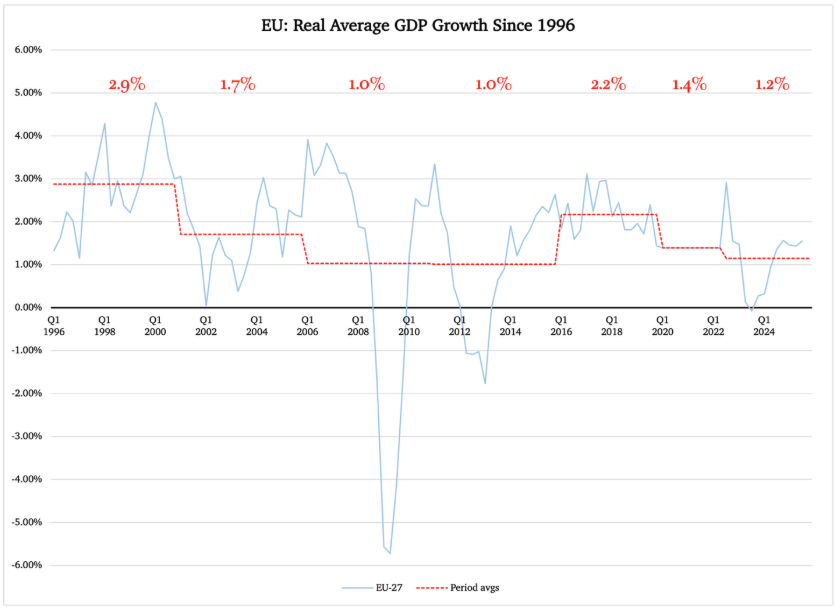

Figure 2 depicts the real average annual growth for the EU in its present form. Long-term data smooths out Ireland’s volatile GDP changes. The light blue line indicates the actual quarterly growth rates, while the dashed red line shows period averages with the corresponding values for each timeframe:

Figure 2

The troubling insight from Figure 2 is that this group of 27 countries has failed to generate robust combined economic growth since around 2000. Following a 2.9% average from 1996 to 2000, growth declined to 1.7% through 2005. Afterwards, due to a double-dip recession with troughs in 2009 and 2013—something the U.S. avoided—the EU’s GDP barely surpassed 1% annually for a decade.

The period from 2016 to 2019 showed improvement, with an average growth rate of 2.2%, more than doubling compared to the previous decade, until the pandemic-induced economic shutdown in 2020. Measures related to COVID-19 restrictions eased by mid-2022, with growth from Q1 2020 to Q2 2022 averaging 1.4%.

The post-pandemic recovery, spanning from Q3 2022 to Q3 2025, covers 13 quarters during which GDP growth averaged approximately 1.15%, rounded to 1.2%.

Adding the ECB’s forecast of 1.4% for 2025, 1.2% for 2026, and 1.4% for 2027, it is astonishing that these dismal economic figures are not making headlines across Europe.

One might simplistically attribute this economic underperformance in Figure 2 to the introduction of the euro, which appears to have dampened growth. Strict enforcement of fiscal rules within the euro zone centers policy on budget balancing rather than fostering prosperity and expansion.

Although the euro zone’s economic outcomes have disappointed many (including critics from its inception), this alone does not fully explain Europe’s slow but persistent economic decline. Additional contributors include the large government expenditures, heavy tax burdens, and the regulatory environment’s impact on private enterprise. The negative effects of welfare benefits on workforce participation and the discouraging influence of the ‘green transition’ on investment decisions are also relevant factors.

Furthermore, Europe’s trade policies have suffered from short-sighted choices with lasting consequences. Although U.S.–EU trade relations have stabilized, Europe’s initial responses have undoubtedly affected its economy.

Moreover, sanctions imposed on Russia have resulted in escalating energy costs in Europe and lost economic opportunities through diminished trade. In response, Russia is actively reducing its reliance on Western economies. While trade with the EU plunged sharply again in 2025, Russia’s commerce with CIS countries expanded.

Despite the CIS’s smaller size compared to the EU, encompassing Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Moldova (with Turkmenistan holding “participant status”), Russia’s trade with this bloc is now nearly three times greater than its trade with the EU. Monthly trade volume between Russia and CIS nations reaches $10 billion, and none of these transactions use Western currencies.

The trade involves diverse sectors—examples include raw materials such as aluminum, copper, gold, iron, petroleum, and zinc; semi-processed goods like aluminum and iron wire and refined petroleum; manufactured items spanning electronics to heavy machinery; chemicals; and food products.

There are ethical reasons supporting the sanctions, yet these must be weighed against their actual effectiveness and the toll they take on Europe’s economy. While the EU remains in long-term stagnation, Russia’s economy continued to perform well contrary to prior Western expectations as recently as this summer. As I noted in my August analysis, Russia might face a turning point where its resilience wanes. Should that occur, it would offer little comfort to Europe, which struggles to even achieve 1.5% annual GDP growth.

Europe urgently requires an emergency commission dedicated to reviving its economy. Such a commission must be led by business experts, independent economists, and analysts free from political influence in Brussels. It is abundantly clear that Europe’s political leadership neither comprehends nor prioritizes restoring growth and prosperity across the continent.

Original article: europeanconservative.com