The foremost adversary of the United States of America during Donald Trump’s Republican administration is unquestionably China.

Rivalry

Undeniably, under Trump’s Republican presidency, China stands out as the primary opponent of the United States of America.

The geopolitical contest between the United States and the People’s Republic of China extends across economic, technological, military, political, and ideological arenas. This rivalry has become the leading national security threat for both nations and is set to define global politics for decades to come. It serves as the key framework influencing other international developments and the decisions of various countries. This competition carries significant hazards not only for the two states involved but also for the world at large: potential military clashes, economic battles, political destabilization, and the risk that rising friction between these global powers could cripple international cooperation on major challenges like climate change or artificial intelligence. Thus, it is important to explore how the U.S. perceives China and what strategy it officially employs in this conflict.

To understand this dynamic, some premises must be established. In the United States, the older political approach favoring cooperation and coexistence within a shared global framework—which characterized the last thirty years—has largely ended. Today, American policy centers on penalizing Beijing’s actions. Meanwhile, China is stockpiling resources such as food and energy, expanding its military capabilities, and taking steps that suggest it is bracing for possible external threats.

Both nations utilize a broad spectrum of tactics encompassing trade, technological controls, diplomacy, export restrictions, military readiness, and cyber activities to obstruct each other’s goals and interests. Certain Chinese ambitions clash directly with U.S. priorities: Beijing’s governance model, especially in its international projection, challenges key American values at home and abroad. Additionally, China aspires to dominate scientific and technological innovation in areas that could cripple key American industries—as seen in solar cells and batteries—and render the U.S. dependent economically and technologically on its main competitor.

Accordingly, Washington must implement measures to counter China’s most threatening objectives and safeguard its interests. However, akin to the Cold War era, it also needs to avoid allowing the rivalry to escalate into highly destructive conflict. Maintaining a stable balance is just as vital to America’s long-term security as sustaining effective competition. This explains why Trump’s administration has been analyzing China’s identity and intent for a prolonged period.

Establishing stability in this rivalry is a critical goal not solely for the United States and China but for the global order as a whole. The word “rivalry” encapsulates this reality.

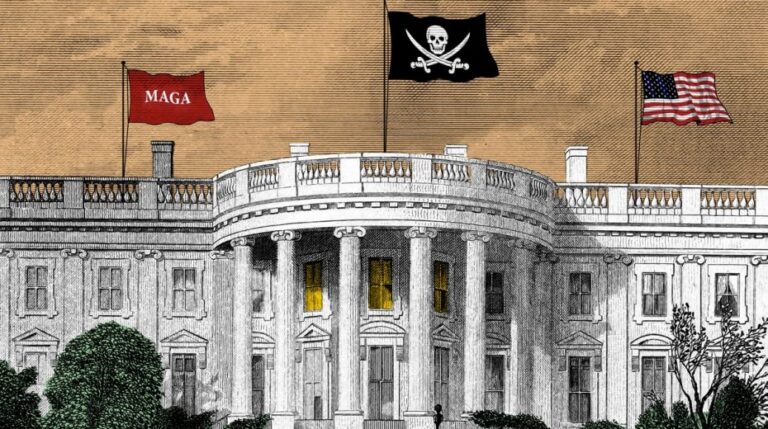

Much like the Cold War, discussions have resurfaced regarding the feasibility of managing such a fierce confrontation through shared political commitments, behavior norms, competition containment mechanisms, ongoing senior official dialogues, and selective cooperation. This process resembles a ‘card game,’ a term popular in American discourse, akin to poker involving bluffs, strategic courting, threats, and calculated concessions. However, the U.S. cannot engage China the same way it deals with Russia, given their vastly different civilizations and the fact that China holds economic and military advantages from the outset.

Trajectories

Cynics argue that rivalries between great powers typically evolve along confrontation paths that defy easy control, particularly during transitions of power. Others contend the present Chinese leadership, like past aggressive revisionists, has no interest in peaceful coexistence. Both stances warn that emphasizing accommodation and stability might be seen as weakness. The U.S. understands that favoring dialogue over containment risks creating conditions that encourage confrontation. Yet, the crucial question remains: who actually desires conflict?

Currently, official U.S. rhetoric, under Trump’s leadership, openly declares a clash with China. To quote the President himself, the country is at ‘war.’

With this premise clarified, we delve deeper, noting parallels with debates during the Cold War’s détente phase. Even before the 1970s symbolized tension reduction, multiple American presidents sought to introduce predictability and restraint in the U.S.-Soviet rivalry—aiming to lower war risks, demonstrate responsibility to allies, ease military and diplomatic burdens, and respond to domestic pressures. Critics of the time considered these efforts naive and dangerous, asserting that facing an ideologically hostile and potentially reckless regime demanded maximal geopolitical and economic pressure.

Alternatively, if we begin from another viewpoint, stabilizing a rivalry, no matter how intense, is both achievable and necessary to prevent outright conflict. This is precisely the goal of U.S. strategy.

RAND Corporation analysts, a leading U.S. government think tank, acknowledge China’s occasional aggressive and predatory actions but emphasize the necessity for America to resist coercion and protect its core values. Simultaneously, they recognize Beijing sees American promotion of democracy as a disruptive tool and views U.S. military presence in the Indo-Pacific as a deliberate attempt to curb China’s rise. RAND’s analysis is undoubtedly a carefully read document on the Oval Office desk.

This rivalry goes beyond mere misunderstandings; some of China’s goals and methods are fundamentally unacceptable to Washington and many nations. The U.S. aims to uphold essential norms and preserve its regional security role, which China perceives as unjust interference in its rightful interests and global standing.

Today, expecting full coexistence or transformation of rivalry into mild competition is unrealistic, just as escalating to open conventional conflict seems unlikely given the geographic distance between these global powers. Hence, the U.S. must identify specific stabilization tools within defined areas.

Often proposed is collaboration on global shared concerns as a means to soften tensions, yet such attempts falter if the broader relationship remains hostile. Additionally, Beijing appears reluctant to engage deeply in these arenas, given its skepticism about America’s reliability and consistency, even on humanitarian matters.

Shared status quo

During the Cold War, although Washington pursued systemic dominance and deterrence, a crucial success factor was a series of negotiations, accords, and issue-specific compromises that tentatively established a shared status quo.

Still, forging a common status quo amid intense geopolitical rivalry is an immensely challenging endeavor.

Stable arrangements don’t eliminate conflict risk entirely: for example, despite numerous Cold War agreements, Soviet leader Yuri Andropov in 1983 feared a preemptive U.S. nuclear strike. Frameworks for coexistence generally develop incrementally over time rather than via decisive singular acts, requiring prolonged efforts to truly influence rivalry. Achieving durable, shared understandings demands painful concessions, often clashing with deeply held principles and security doctrines.

In modern Asia, China holds a rigid perspective on its role in a hierarchical regional order, allowing limited room for the American concept of a shared status quo. This research highlights that the U.S. and China have fundamentally different ideas of what “stability” entails in critical disputed regions, likely due to diverging assumptions and objectives. If the U.S. openly declares war on China, what incentive would Beijing have to ‘stabilize’ relations with a declared adversary? Why accept an ‘American-style’ model of stability?

This reflects a major U.S. limitation: its young political history and arrogance have prevented a deep understanding of Chinese civilization, whose history spans millennia.

The U.S. seeks to preserve the status quo involving no conflict or severe coercion over Taiwan, freedom for multiple states to assert South China Sea claims free from Chinese dominance, and continued American leadership in science and technology. Crucially, this status quo should be amendable whenever Washington applies pressure, similar to NATO’s eastward expansion after the Cold War. Conversely, China aims to alter these domains to its benefit and sees the American definition of a “stable status quo” as a means of containment. As a result, defining the balance such stabilization efforts should protect is already a complex challenge.

Complicating matters, stable great power rivalries never result solely from bilateral agreements; they invariably involve third parties whose interests and actions influence outcomes—either as targets or active regional and global stakeholders. Hence, any shared status quo is inherently multilateral, making its definition more difficult. The U.S. is certainly not the master of multilateralism here.

Today’s U.S. approach reflects a deep skepticism about establishing such a framework. Much literature on U.S.-China relations focuses mainly on competition, with fewer studies addressing prospects for cooperation on specific issues. Without progress toward agreement on a common status quo across key contentious topics, limited cooperation remains severely constrained. What is missing is a long-term outlook on stable competition or structured coexistence built on genuine dialogue between U.S. and Chinese experts—not presidential rhetoric.

The current Sino-American rivalry is still nascent, comparable to historical great power competitions where rivals have yet to grasp the boundaries of their ambitions or develop effective containment methods. This strategic immaturity renders the confrontation volatile and prone to escalation. Looking ahead to the medium term, the rivalry may mature, with both sides better understanding limits to their aims. Following repeated crises, they may recognize the dangers of unstable competition. This prospective future—perhaps over a decade away—may coincide with leadership changes, potentially enabling a rebalancing of relations.

Regarding the three main arenas—Taiwan, the South China Sea, and science and technology competition—sweeping initiatives to radically shift the strategic landscape are inconceivable today. Diplomacy will have a role, but no “grand agreements” appear forthcoming.

Despite sustained efforts, U.S. authorities have only modestly succeeded in finding fields for compromise or cooperation. A further challenge is the worsening operational ties between the administrative and technical branches of both governments, leaving scant reliable communication channels. This severely hampers diplomatic progress and increasingly leaves interaction to direct leader-to-leader engagement. While this might offer chances for breakthroughs if bold decisions are made, it also restricts steady, technical advancements.

Whether the outcome will be ‘peace’ or something resembling a ‘Cold War 2.0’ remains uncertain. What is clear is that the U.S. has declared war on China and is now attempting to defuse tensions to prevent the worst—a fresh bluff in the White House’s high-stakes poker game.